REVIEW: Kitchener’s biennial IMPACT Festival crackled with urgency

IMPACT Festival is a name that invites challenge. Though it doubles as an acronym for International Multicultural Platform for Alternative Contemporary Theatre, the word “impact,” considered in the context of a performing arts festival, raises an important but intimidatingly broad question: What does it mean for a performance to leave a genuine imprint on a community?

This query reverberated through my time in Kitchener, Ontario at the ninth iteration of MT Space’s biennial event, which featured a curated lineup of over 20 artistic offerings, spanning dance, theatre, and installation — a few originating across the world, with many more hailing from the Waterloo region and/or the rest of Canada. Most of the six works I viewed tackled urgent topics, from the convoluted Canadian immigration system to the Palestinian experience of displacement: explorations that line up with artistic director Pam Patel’s curatorial statement, which discusses how IMPACT ‘25 “unpacks what it means to survive, to resist, and to seek refuge” through a global, Indigenous-focused lens. For me, the gift of the festival was that at every show, it was utterly clear what Ontario audiences might take away.

***

Two plays about immigrating to Canada bring specificity to a massive subject by personalizing it in very different ways.

A co-production between Kawalease ACT (Arab Canadian Theatre) and Swallow-a-Bicycle Theatre (here presented in association with Kitchener’s Mada Theatre), The Opposite riffs on the fact that Canada resettled more than 44,000 Syrian refugees between fall 2015 and the end of 2016. Through a daring participatory format, creator-director Sleman Aldib’s production considers what it would be like if the situation was reversed, with Canadians seeking asylum in Syria.

The small sold-out audience gathered in the lobby of Kitchener City Hall. After a pre-show speech explained that the coming experience was designed to be “somewhat uncomfortable,” Aldib handed out one-page forms written in Arabic, and prepared us to go through the immigration centre’s doors.

On entry, the atmosphere was evocatively overwhelming. Arabic hailed down from every direction: wall signage, radio music, employee banter. After letting me flounder for a few seconds, an officer pointed me toward one of several stations. There, I and a couple of other spectators learned four of Arabic’s 28 letters. Once I was able to pronounce and write them correctly, the station’s officer checked off a bubble on my sheet, and directed me to another station, where I got my photo taken. From here, the task became clear: Hop from station to station to fill in my sheet. This involved eating a Syrian snack, getting my thumbprint taken, and having a medical checkup.

It also meant a lot of beration. For those who didn’t speak Arabic, the onus was on us to figure out what was going on through hand gestures and tone of voice. And if you couldn’t keep up, there were consequences: Toward the end of the experience (billed as 105 minutes, though it ran short on opening night), an impatient doctor tore my immigration sheet, forcing me to start the process over again. Eventually, I started feeling grateful to the officers who offered even a glimmer of a smile. Fluent Arabic speakers seemed to have an easy time, but it was interesting watching people who were half-fluent, often seemingly children of native speakers: In a way, they appeared more stressed about not understanding everything than those of us who could just surrender to not knowing.

I sometimes found myself wondering if the game’s difficulty level could be raised — while that first step into the room was intense, the structure is ultimately straightforward, and, at a point, the experience became more fun than uncomfortable. That said, I’m an atypically frequent theatre-goer, and therefore am used to audience participation; toward the end of the show, I heard a spectator near me whisper: “They were so mean, I cried a couple times.” So responses will evidently vary.

The escape-room elements eventually fall away, and the show concludes with out-of-character English-language monologues from each of the eight performers. In them, we learn that for this iteration of the show, most of the actors are local and non-professional (the notable exception being Aldib, artistic director of the Calgary-based Kawalease ACT). They share their own experiences of the Canadian immigration system, and affirm that yes, this was really how it felt to arrive here. This reveal unlocks a resonant double meaning in the play’s title: that the actors, too, have spent the show embodying “the opposite,” and briefly reclaiming some agency over their life in Canada.

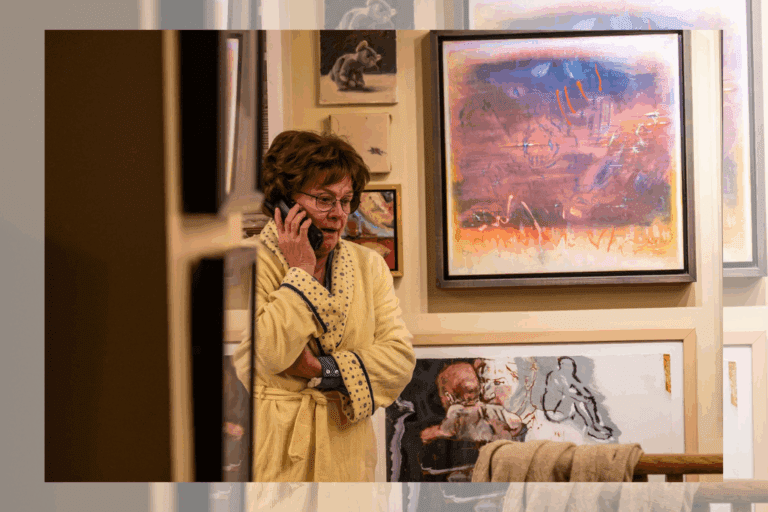

Non-professional performers also anchor Outta Work Actors Inc.’s The Canadian Dream, presented in a rehearsal hall at the Conrad Centre for the Performing Arts. Before the show, co-directors Tanya Williams and Heather Majaury explained that the devised theatre piece came out of Kaleidoscope, a community-based laboratory drawing on applied theatre techniques including those inspired by Augusto Boal. The local performers then introduced themselves before leaping into the 50-minute-ish drama.

Protagonist Rahul (Shubham Maheshwari) immigrates from India to Canada to attend university and start a career in Kitchener’s tech industry. Though he lands a job right out of school, mass layoffs soon leave him unemployed and barrelling toward homelessness. This relevant but relatively uncomplicated narrative takes on an extra layer of interest because of what the audience knows about the performers’ real lives: Maheshwari is himself an immigrant of two years, while his unforgiving landlord is played by a professional in eviction prevention (Leah Connor). The staging is low-tech, but features a handful of creatively staged sequences.

Although the festival program did not explicitly label The Canadian Dream as a workshop production, Majaury made it clear that this presentation was just one step in the development process: During the next couple of months, the show will appear as a multi-hour forum theatre experience, in which audiences will respond to the piece via a series of prompts and games. Based on the passionate responses that emerged during the brief post-show Q&A, I expect interesting results.

***

Amid Israel’s genocidal violence in Gaza, it was welcome that IMPACT platformed multiple works from Palestinian artists, including a pair that involved young characters.

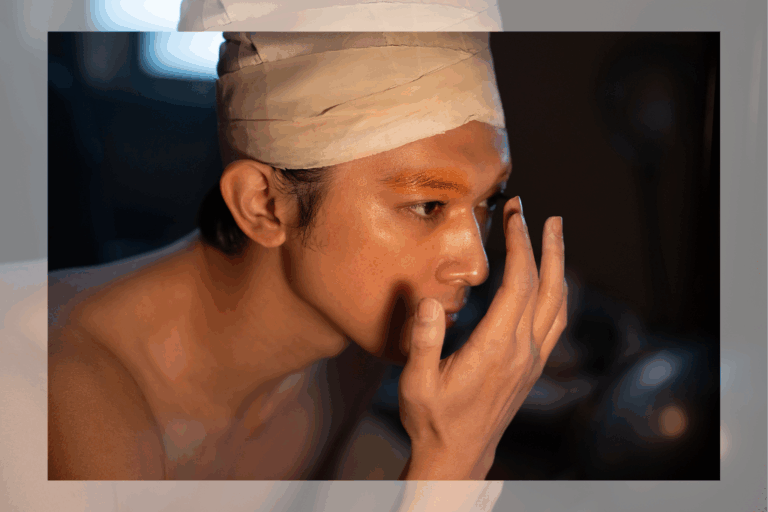

Toronto-based writer-director Rimah Jabr’s This is Not What I Want to Tell You imagines resistance as a natural bodily function. For the solo show’s 15-year-old protagonist (Nada Abusaleh), this manifests through a habit of sleepwalking. She tells the audience that first, she unknowingly peed on the family couch; then, she perambulated naked through her village; and finally, she advanced toward a nearby settlement with a knife — landing her in a detention centre.

The character spends most of the play’s 50-minute runtime sorting through her memory, reminiscing about her family life and trying to figure out whether she actually committed a crime. Abusaleh’s performance is remarkably deliberate; an adult playing younger in uncanny makeup, she maneuvers Jabr’s crystalline text with scalpel precision and moves with intention, drawing on stillness when appropriate.

Above Abusaleh hangs a clothesline holding four art works by scenographer and visual artist Bianca Guimarães. A pre-show speech explains they’re cyanotypes — cameraless photos created with the sun’s help, developed under UV light. As the show progresses, Abusaleh fills two more clotheslines with the large blue fabrics. In many of these elegant, surreal pieces, slightly disfigured children seem to overlap with their environment. There’s a paper head, a concrete pair of beat-up kneecaps, and a dress made of splintered wood. Though Jabr based the play on a wave of knife attacks by Palestinian teenagers in 2015 and 2016, these images powerfully expand the piece’s implications beyond one specific girl, in one specific time.

As part of This is Not What I Want to Tell You’s highly theatrical ending, the protagonist reads out a letter to her sister Lena — creating a fortuitous parallel to the epistolary-esque Dear Laila, an interactive installation by the U.K.-based Basel Zaraa. Similar to how The Opposite evoked empathy by placing the audience into an immediate relationship with its subject matter, in this 20-minute experience for one viewer at a time, you are the titular Laila, Zaraa’s five-year-old daughter.

An IMPACT volunteer welcomes you into a small, dimly lit building at Schneider Haus National Historic Site. You sit down at a table, on which rests a model of a two-storey concrete building. To your right, headphones connect to a cassette player. You press play.

Zaraa’s voice greets you and explains this is his childhood home, part of Damascus’ Yarmouk refugee camp. He recalls the compact, no-frills living space with ambrosial warmth. I use past tense because you eventually gather that this building is now rubble. All that remains are photos, remarkable for their un-remarkability, collected in an album in front of the model. Today, Zaraa’s family splays across the globe.

In the context of a theatre festival, Dear Laila stands out for its self-directed nature. While the experience flows intuitively, it demands presence and active engagement. Zaraa doesn’t tell you how to interact with the installation, or when to move on with your day. He just shares the truth.

***

Two less obviously topical productions, both in conversation with urban landscapes, primarily resonated on a formal level.

It was my first time seeing Flush Ink Productions’ Asphalt Jungle Shorts, a Kitchener theatrical tradition in which the city’s downtown becomes the stage for a series of 14 new site-specific plays. The content warnings on the IMPACT site make it evident that the project’s ethos is to embrace the unpredictable: “Be prepared to get your steps in. Wear your walking shoes. Leave the kids at home… If it looks like rain, bring an umbrella.”

This 21st iteration of Asphalt Jungle Shorts began behind Kitchener City Hall. The performance started without preamble, as a man in a construction vest (John Dibben) approached holding a sign advertising a “FREE HUG.” After following through on his offer with the bravest of the audience — as well as a clingy character played by Taras Rudyi — the walking tour began, led by the stop-sign-waving Dibben and bearded sidekick Sam Bentley.

Performed by a team of one to three actors (some of whom appeared in multiple segments), the plays unfolded in parks, doorways, courtyards, sidewalks, and more. Many took a slice-of-life approach, involving low-stakes conversations like ones you’d hear on the street. In general, these exchanges engaged me less than real-life people watching, because the exposition flowed too easily (part of the fun of eavesdropping is the struggle to work out who’s speaking).

But a few plays went to more heightened places. Such was the case with a pair of athletic collaborations between Rudyi and director-performer Maria Colonescu: “Guard(ian),” a contemporary dance routine inside a large metal cage near city hall, and “A Regimen,” which involved Rudyi lifting weights before exhausting himself by running laps around a field of grass. These pieces were interesting because they felt like a transgression of usual city life, rather than an attempt to blend in. I also enjoyed the promenading transitions between plays, complete with dry improvised banter from Dibben; so it was disappointing when, a few plays before the end, Dibben disappeared, and Bentley led the group silently.

Asphalt Jungle Shorts’ most unpredictable performer was the city itself. During a playlet that wasn’t really working, I turned away from one character because another appeared behind me. After I readjusted to better watch this second performer, the first one started talking again, and when I looked back, a tree gorgeously framed her face; the gap in the leaves seemed made just for her.

During a romantic play on a bench, it started to rain. The audience immediately erected a ceiling of umbrellas; the performers huddled under one, too. Next to us, a brightly lit parking lot ramp spiralled upward. There was something strangely beautiful about the contrast between us eager, damp theatre-goers, destined to leave in a few minutes, and the permanence of that looming garish concrete corkscrew.

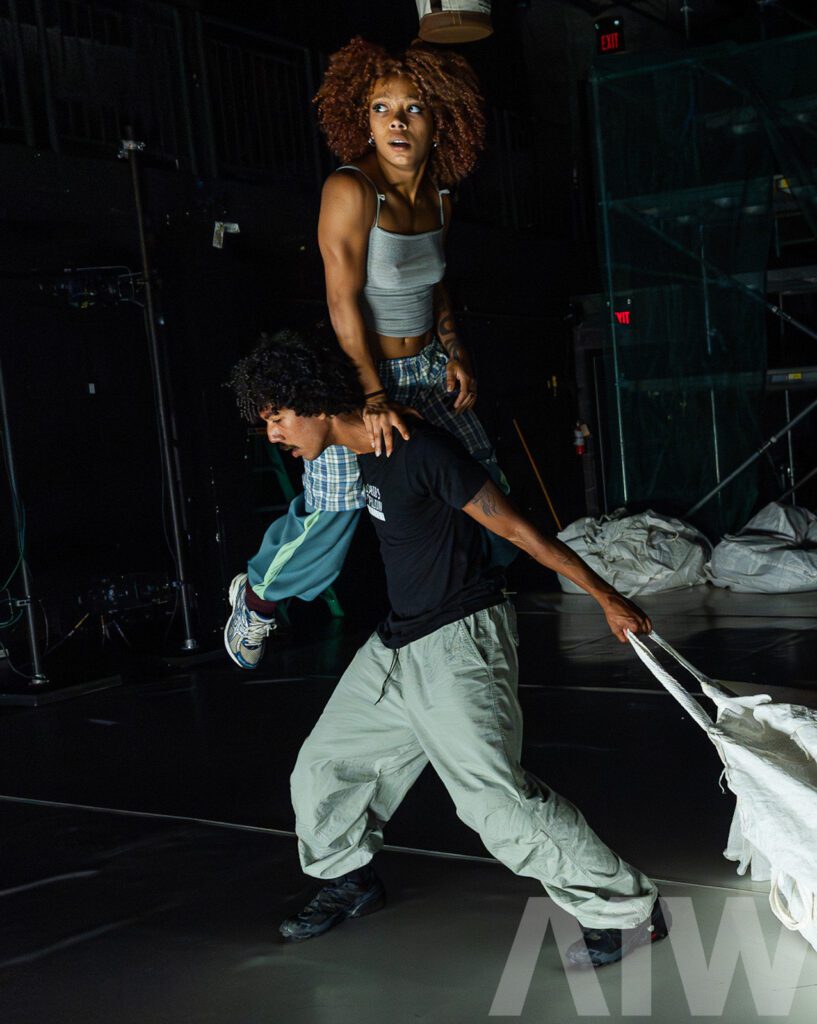

At the Conrad Centre’s Warnock MacMillan Theatre, the volatile contemporary dance show Bogotá acted as the fire to Asphalt Jungle Shorts’ rain. Choreographed by the Colombia-born, Montreal-based Andrea Peña (in collaboration with the company of nine dancers), the production takes inspiration from the turbulent, constantly shifting nature of its titular city.

When the dancers enter, they languish, shirtless, across Peña and Jonathan Saucier’s roving set, which contains a towering piece of metal scaffolding, a narrow sheet of plastic, and a mound of black speakers. Eventually, a few dancers unite on a wheeled set of metal bars, and the 75-minute piece begins to crescendo, both physically and musically. (Sound composer Debbie Doe’s score mixes looping choral hymns, electronic dance music, and rainforest noises.) As it progresses, there emerges a pattern of intense rise-and-fall — or death and rebirth — which manifests in contrasts between loud and soft, clumped and scattered, high and low, violent and tender.

Not being very knowledgeable about either contemporary dance or the history of Colombia, I think I’d need one or two more viewings to start processing the complex postcolonial commentary at play here; the piece invokes Colombia’s flag and national anthem, and Peña’s website states that it’s in conversation with Andean Baroque architecture. Impressively dense intellectual layers aside, Bogotá’s throbbing brutalist aesthetic grabbed me on a visceral level. It was hard to miss the transgressive spirit behind a sequence where one dancer destroys a pinata as another stands on the speakers and convulses her shirtless body, middle finger to the sky.

***

I left IMPACT appreciating these productions’ thematic and aesthetic risks. But I’m also cherishing the moments between the shows, when community flourished.

On the way out of The Opposite, an actor who I don’t know gave me a bear hug, and joyfully said: “I’m sorry I was so mean to you in there, man!”

Gathering in a circle ahead of Asphalt Jungle Shorts, spectators exchanged IMPACT recommendations, with someone remarking: “This festival is incredible. I can’t believe it happens here.”

During the fading seconds of The Canadian Dream’s Q&A, a woman next to me propelled the conversation beyond its natural end, proclaiming that she loves “this type of theatre,” before rousingly asking how we might advance from performance to action: “How can we change this awful situation?”

And after every performance, an artist would warmly invite the crowd to the festival bar, which hosts music, drag, and more.

These are small impacts, and ones that mainly affect the festival’s existing audience base. But they add up.

IMPACT ’25 ran from September 23 to 28 in downtown Kitchener. More information is available here.

MT Space generously sponsored accommodation for Intermission’s review coverage of the festival.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments