REVIEW: A Poem for Rabia at Tarragon fits a large story into a small space

If I had a nickel for every 2023 Tarragon show that interweaves a 21st-century setting with an older one, stars the playwright as a queer Canadian trying to make sense of the world, and features a pool of real water at the front of the stage, I’d have 10 cents.

The first was Makram Ayache’s The Hooves Belonged to the Deer in April. The second is Nikki Shaffeeullah’s A Poem for Rabia, produced by Tarragon in association with Nightwood Theatre and Undercurrent Creations.

While the former made up for fuzzy performances with explosive aesthetic highs, the latter works somewhat oppositely. On a scene-to-scene level, co-directors Clare Preuss and Donna-Michelle St. Bernard render Shaffeeullah’s ambitious text with impressive clarity, ensuring the actors are supported in their traversal of the play’s manifold shifts. The dramatic foundation of A Poem for Rabia is well in place; it’s the visual concept that’s in need of greater love — and, perhaps, a larger canvas than the intimate Tarragon Extraspace can offer.

Shaffeeullah plays Zahra, an activist living in Canada in the year 2053. Though the country recently abolished prisons, she feels disconnected from her ancestors, and worries her contemporary lifestyle is turning her into a “fairweather descendant.”

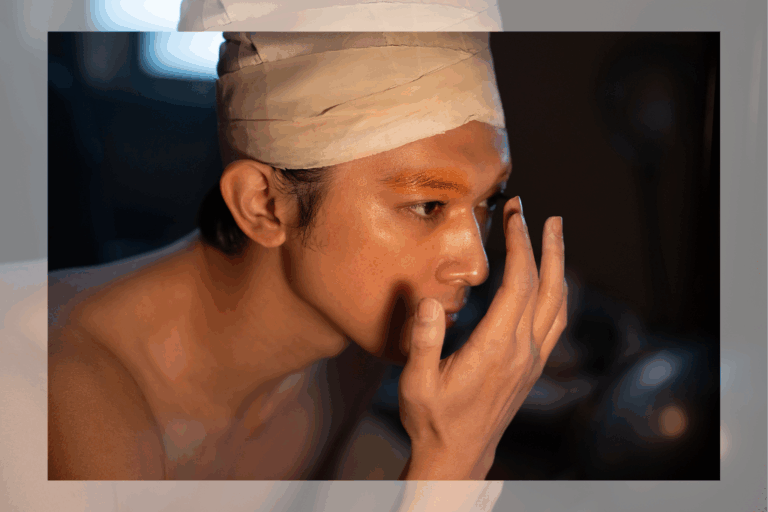

The play brings to life two such ancestors, interweaving their stories with Zahra’s. One is Betty (Michelle Mohammed), a secretary starting work at the Governor of British Guiana’s office in 1953. Another century back lives the titular Rabia (Adele Noronha), an Indian domestic worker being sent to the Caribbean on an indentured labour ship helmed by colonizers.

All three live through times of immense political change. But Shaffeeullah doesn’t coat their lives in drama. Instead, A Poem for Rabia focuses on the smaller joys and disappointments of everyday life — the nervous excitement that accompanies a new job, the embarrassment-tinged thrills of awkward conversation, and the delight of exploring new foods (along with the comfort of indulging in old ones). Despite the vast temporal gulf separating the women, Shaffeeullah’s attention to detail connects them: their emotional and spiritual journeys intersect even as their literal circumstances diverge.

The show’s double casting contributes to this sense of overlap. Virgilia Griffith, Jay Northcott, and Anand Rajaram each play characters in two of the timelines, blurring the differences between the worlds. The grounded performances of the central trio of women keep things from becoming unclear, however — Mohammed, in particular, anchors her setting with fire and dynamism.

It’s becoming somewhat common for Toronto playwrights to star in their own shows, but Shaffeeullah gives herself a fairly laidback role — Zahra’s emotional range isn’t huge, and she speaks less than one might expect. Shaffeeullah’s casting also helps underline her personal connection to the material (her playwright’s note hints at parallels between her family history and Zahra’s).

Sonja Rainey’s sea blue set doesn’t evoke a specific time or place. Instead, it’s an abstract jungle gym of sorts; a couple of inclined slopes and a blocky upstage platform serve as perches for the actors, allowing Preuss and St. Bernard to create unique stage images.

The semi-circular pool of water is less effective, however: it occupies downstage centre, and a barrier cuts it off from the rest of the playing space; since it’s only really used in one late scene (Chekhov’s pond, yes), this placement feels unearned — though the payoff of the pond scene is sweet, I’m not sure it’s worth losing prime stage space elsewhere. And when scenes take place on the ground behind the pool, the barrier cuts off the actors’ legs, leeching their energy.

Any show that interweaves settings puts a great deal of responsibility on the lighting designer; especially if there aren’t many set changes, they tend to be tasked with dividing and defining the space. Echo Zhou 周芷會 takes up this challenge admirably, offering expressionistic flourishes in addition to clearly signposting the play’s shifts. But a large, foil-like wall at the back of the stage at times muddies Zhou’s work — it’s a reflective surface, so it smudges the light, making it difficult to isolate characters in spotlights without light flashing forward.

A Poem for Rabia feels a little trapped in the Extraspace — at two-and-a-half hours, Shaffeeullah’s play is big, and could use more space to breathe. (It would even be fascinating to see what a film or novel adaptation would do with the sweeping story.)

But the show’s passionate core comes through nonetheless. Though the character Rabia does write a poem, it’s moving that the play’s title speaks of a poem “for” Rabia, not “by” her; A Poem for Rabia is ultimately a circular gesture, a loving handing back of what’s been passed down.

A Poem for Rabia runs at Tarragon Theatre until November 12. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments