REVIEW: Two hybrid dance pieces close out this year’s SummerWorks Performance Festival

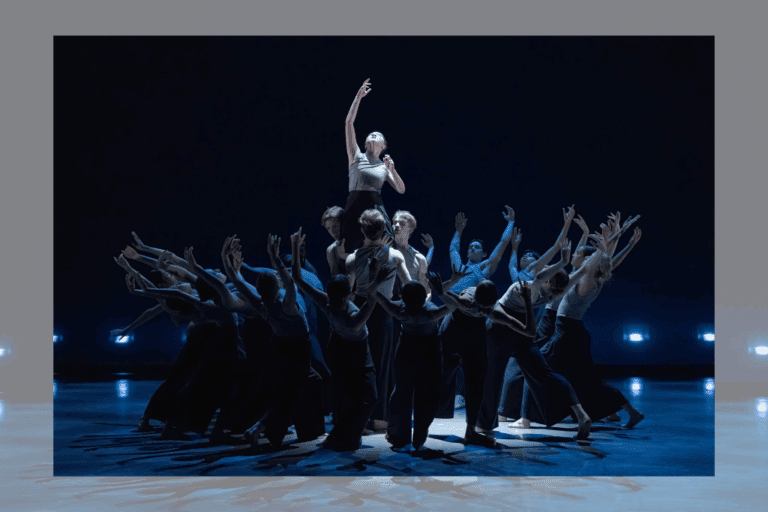

Toronto’s annual SummerWorks Performance Festival tends to offer an endurance test for the imagination where you can tumble from one genre-bending performance into another as the city’s theatres become laboratories for the avant-garde. In its closing weekend, I saw two works that live side by side in my memory even as they differed in style and intention. Both explored memory, loss, and the body’s way of carrying history — one did so with devastating intimacy, the other with cerebral play.

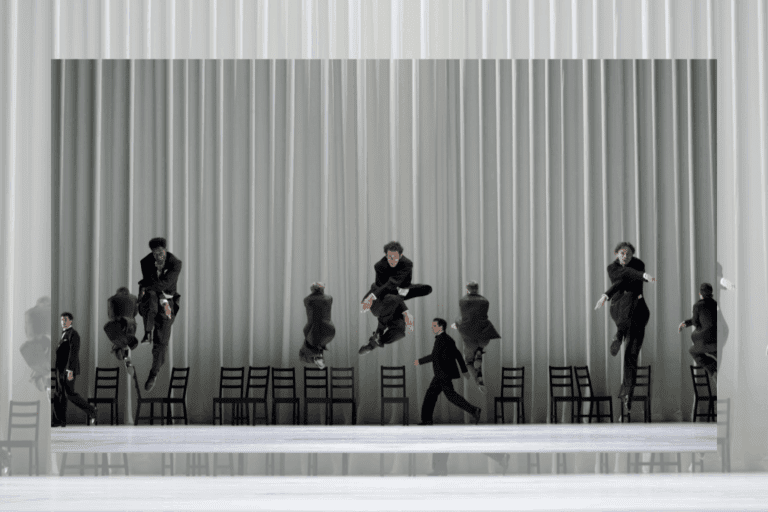

Je ne vais pas inonder la mer (I Will Not Flood the Ocean) [The Theatre Centre, BMO Incubator]

Sonia Bustos, the Mexico-born Montrealer, wears just about every hat — director, choreographer, performer, and set designer — in her solo dance performance Je ne vais pas inonder la mer. The title, which translates to I Will Not Flood the Ocean for most of us in Toronto, is puzzling. It almost sounds like a personal commandment but it carries a private weight. In a post-performance Q&A, Bustos explained that her mother died when Bustos was just 20 years old. She worried her tears might never stop and turned to her therapist for advice — they replied, “you cannot flood the ocean.” The phrase, both tender and abstract, lodged deep within Bustos and became the basis for the show, which explores not only her loss but also captures the oceanic depths of grief itself.

About 25 chairs were set onstage in a square, close enough to hear Bustos’ breath. Each corner had its own installation: a chair next to a side-table topped with flowers in a vase and a glass of water, a stove and pot on a counter, a trunk draped in a blanket, and a short box heaped with dirt — a grave, perhaps? Low amber lights designed by Catherine FP blurred the edges of these stations, and a sweet, spiced scent flooded the room. It was immediately clear that we were seated in Bustos’ memory palace.

The work unfolded in loosely three acts without intermission. It opened with bare-footed Bustos drifting around the stage in a half-committed two-step to Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” as club lights flashed. It felt like we were watching a memory, but whose? Bustos’, her mother’s — or some combination of both? What began as a gentle groove quickly evolved into jittery steps, then grew into erratic and finally frightening movements that forced Bustos to collapse on the floor. This was her first portrait of emotional darkness and a display of her most successful device — letting horror break the structure of the dance until only raw emotion remains.

The second act seemed to circle around Bustos’ personal experience of the loss of her mother. After leaving the audience in total darkness until I wondered if the lights weren’t working, she appeared standing atop the mound of dirt under a golden spotlight illuminating the sweat and tears on her face. A ghostly a cappella group (Eloisa Reséndiz, Kali Niño, Yanin Alvarado, and Sergio Barrenechea) sang a mournful tune behind her as she knelt down to squeeze clumps of dirt, then slowly crawled through the dirt in pain, dragging herself across the floor as if to exhume memory itself. The spareness of it all was brutal, and I found myself wiping tears from my face, embarrassed to be crying so publicly. The palpable wish to bring her mother back was more resonant than I came prepared for.

The final act turned toward healing. Bustos brewed decaf coffee (which we heard about in an announcement proceeding the show) in the Latin American style, laced with sweet cinnamon, and served it to each audience member in mugs carried from Mexico — another tidbit discovered in the Q&A. As she passed the bitter drink lovingly into our hands, smiling at each of us as the aroma wafted through the room, comforting us in a way she had once been comforted. Finally, the singers came out to the stage, this time playing small instruments and taking turns singing lively Mexican folk tunes. Bustos put on a pair of red shoes and began stamping in time with the music. It was joyful and necessary to the story’s arc, but I felt this section of the show sustained its one note for too long. But perhaps that was the point: grief’s afterlife is long, sometimes too long, and consolation can feel like an endless process.

Je ne vais pas inonder la mer left the impression of an artist opening her psyche with bravery. Bustos invited us into the rawest time of her life and gave us coffee before sending us back out into the light of day.

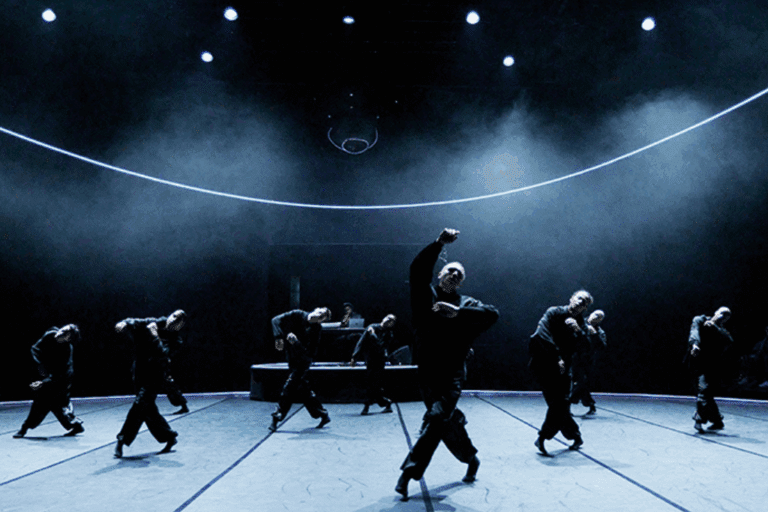

Graveyards and Gardens (Theatre Passe Muraille)

If Bustos’ piece was intimate to the point of confession, Graveyards and Gardens, an hour-long concert-dance-installation hybrid, offered something more cerebral within the realm of memory. I started with high hopes for the performance — Caroline Shaw, the U.S.-based composer, was in 2013 the youngest recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for music. She now works as a composer and cross-genre collaborator whose work bridges classical tradition and artistic inventiveness.

Her collaborator and show partner, Vanessa Goodman, hails from Vancouver, where she’s a professional dancer, choreographer, and the artistic director of Action At a Distance. The pair have been working together on multi-media projects for over nine years. The production was primed to be a thought-provoking duet by two talented artists, but at times the technical experimentation with abstraction in sound overrode chances for deep emotional resonance during its dance sections.

Like Bustos, Goodman and Shaw arranged the audience onstage in a ring around their performance space. A tangle of orange cables formed a séance-like circle around the two artists, connecting half-a-dozen thrift-store lamps, each accompanied by a houseplant and a piece of vintage audio equipment (a record player, a tape deck, a looping station). Goodman and Shaw, dressed in colorful jumpsuits and orange sneakers, sat quietly on the floor, humming, as we filed in.

Before the show began, in the soft and steady tone of a hypnotist about to send us into a trance, Shaw delivered a land acknowledgement and described the work’s themes of returning to the land and the body as an archive for memory with a side of love. She asked us if we would join her in an easy hum, which cued a recorded soundscape of crashing waves. The soundscape rose and fell, then slowly dissolved into machinic pulses. In parallel, Goodman’s dance started with robotic sharpness, her arms folding into exact 90- and 180-degree angles, reminiscent of automated factory equipment, which later became more expansive and intense as the music grew toward its coda.

The piece’s delight lies in its experimentation with sound. In one particularly entrancing sequence, Goodman and Shaw recorded the button clicks of two tape decks, layering them into a percussive loop. Another came when Goodman turned the twist of a light switch into rhythm, looping the clicks into a playful beat that sounded like rain drops or bubble wrap. If the show tells us something about memories, it’s that as we recall them they morph into new, often dazzling forms — as though our minds work like Shaw’s vocoders and sound filters.

Shaw and Goodman have a mastery over sonic texture and as the show continued they wove live vocals, loops, and archival fragments into dense tapestries. The sounds became as tangible as materials but I found myself prioritizing the aural over the visual. There’s no doubting Goodman’s talent, which could be seen in her fitting illustrations of the music — like a bass hit that made her heart pop from her chest. But her choreography read more like additions to the sounds than equal partners to them, and her most compelling moments came not when she was dancing alone but when she was directly working with the props — building loops, singing, or tossing a mic cord around her, rockstar-style — or in the sole instance when she and Shaw moved together, waving their arms in unison.

The piece ended with a return to the waves we heard at the start, giving a final nod to the sense of circular motion explored throughout the show, as well as another request for the audience to hum, this time to a different tune. While Graveyards and Gardens’ short run in Toronto is now over, its collage of looped recordings, repeated lyrics, and sonic gestures might echo in the minds and bodies of the audience like an afterimage — or they might have dissolved back into the ether. For me, it’s both; I’ll walk away with a new reverence for how procedural sounds can become highly playful (in fact, I’m listening to the awe-inspiring tune of my fridge running hot as I write this), but much of the show itself might not stay front of mind.

Taken together, these two SummerWorks performances offered portraits of art at the edges of dance, one personal, one conceptual. Each work brings a sense of the past — whether that’s the loss of a mother or a single moment. They ask if grief and history are not things we should master but things we’re fated to endlessly circle.

SummerWorks Performance Festival ran from August 7 to 17. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments