REVIEW: Soulpepper’s The Comeuppance unpacks high-school reunions with deadly, millennial-aged precision

In the age of social media, what’s the point of in-person reunions?

Is it to maintain tenuous ties with our formerly nearest and dearest who have scattered to the winds? Is it to see what kinds of mess our enemies made of their lives? Or is it simply a memento mori composed of canapés and drinks in a rented ballroom, a reminder that the natural erosion of time comes for us all?

This is a hotly debated topic in Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ The Comeuppance, which contrasts a group of high-school friends pregaming their 20th reunion against their feisty psychopomp alter egos, bone-faced escorts to the afterlife who tell us that all the Jungle Juice and bumping and grinding to Usher in the world can’t bring back the people we used to be.

The show is making its Canadian debut at Soulpepper Theatre, following its 2023 off-Broadway premiere. Directed by Frank Cox-O’Connell, it’s perfect for the extended post-Daylight Saving Time darkness that encourages moody reflection on past regrets. Macabre and drama-filled, yet surprisingly gentle, The Comeuppance will probably be most compelling to the around-40 crowd who share its specific touchstones and millennial angst from a high-school experience bookended by Columbine and 9/11.

Speaking of reunions, Jacobs-Jenkins and I went to college together, and our shared birth year and experiences in the classroom made the show particularly resonant for me; perhaps appropriately, our undergraduate institution has one of the most robust reunion cultures in the world, inviting all students back each year for three days of reflective revelry.

But you don’t have to fit into its characters’ precise age parameters to appreciate Jacobs-Jenkins’ sprawling look at the subtle terror of the passage of time and the choices we make when we feel we don’t have enough of it.

The gathering begins long before the canapés with the soundtrack of any contemporary social event: a call from someone bailing at the last minute. Emilio (Mazin Elsadig), one of those left hanging, is quietly furious. One of the few who made it out of their conservative Maryland town (or “Merlun,” when delivered with the appropriate regional pronunciation), he’s a renowned experimental artist living in Berlin with a five-month-old daughter and a spot in the upcoming Whitney Biennial.

His first return in 15 years should feel triumphant. Yet Jacobs-Jenkins emphasizes Emilio’s discomfort and irritation with his supposed friends, Elsadig’s tense body language showing his raised hackles as he watches the rest of MERG (the “Multi-Ethnic Reject Group,” as they called themselves in high school) failing to thrive.

Stoner Ursula (Ghazal Azarbad) doesn’t want to leave her porch, mostly housebound after losing both her grandmother to COVID-19 and an eye to diabetes complications. Caitlin (Nicole Power, exuding calculated vulnerability) married an older ex-cop who participated in the January 6 riots. And Christina (bahia watson) feels like her service to the armed forces, the medical profession, and her Catholic faith have added more stress than meaning to her life.

As in many of Jacobs-Jenkins’ works, such as Appropriate, there’s an unsettled air of the supernatural hanging over the otherwise realistic gathering. Despite its supposed proximity to neighbours, Ursula’s house feels remote, set designer Shannon Lea Doyle decorating its yard with a lonely angel statue and a wooden swing that eerily rocks itself.

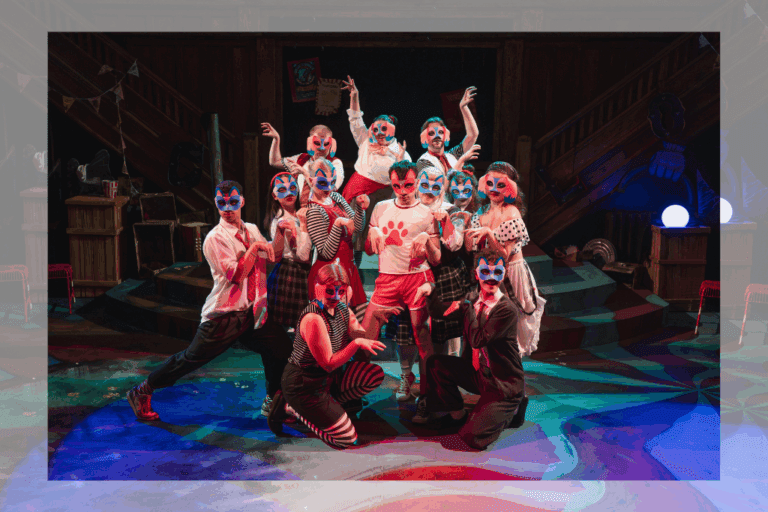

Cox-O’Connell employs blacklight makeup to change the friends’ youthful faces into elaborate grinning skulls as they take turns addressing the audience as Death, a cool effect which works better on some parts of the stage than others. The concurrent distorted vocal echo (sound designer Olivia Wheeler) is also nicely creepy but slightly patchy, and the dialogue between friends could use more amplification overall before louder arguments begin in earnest.

And boy, are there arguments. Twenty years of bile comes out over the course of 130 intermission-less minutes, especially when Francisco (an intense, unsettling Carlos Gonzalez-Vio), Christina’s cousin and Caitlin’s shitty ex who became a soldier, arrives and demolishes what remains of the group’s cohesion. Each character has at least one glorious moment of unraveling — particularly powerful is watson’s plaintive, full-body rejection of her character’s unhelpful husband and house packed with children.

Played with easy familiarity, Azerbad’s Ursula grounds the production. She cites her visual impairment as a reason she doesn’t want to go to the reunion, both a thoughtful nod to the way we try to ignore disability — what’s fun for you might no longer be fun for me, she reminds her friends — and a useful metaphor. The play suggests that reunions serve as depth perception, letting us see the progression of time and how our lives have changed, by superimposing an image of the present on top of the past.

In Jacobs-Jenkins’ interrogation of this past, he offers visceral monologues about the premature weariness and communal rootlessness instilled in many North American teens who came of age between the dawn of modern school shootings and sharply increased surveillance. He doesn’t offer much commentary on the larger picture of these events, instead focusing on individuals grappling with the results of the choices they made in the wake of twin forces of jingoistic patriotism and an increased societal fatalism toward violence.

While the play also speaks frankly about the crushing effect of the pandemic on healthcare workers, I was skeptical of its rosy outlook on the societal togetherness of that time, which seems to ignore those who were forced into contact with the uglier side of humanity.

However, anaesthesiologist Christina’s aforementioned meltdown, which raises the spectre of COVID as a metaphorical sixth face of Death, does speak to the value of even occasional in-person interaction: if nothing else, reunions remind us that we’re all still alive.

At least, for now.

The Comeuppance runs at the Young Centre for the Performing Arts until November 23. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments