REVIEW: Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha at Volcano Theatre/TO Live/Luminato

When a show’s title comes complete with a composer attached, it often feels like a crass marketing move. The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess? Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella? Um. Who else would these shows be written by?

In the case of Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha, however, the king of ragtime’s name deserves pride of place at the beginning of the title. It’s about time he got proper recognition for his contribution to the operatic canon.

Yes, opera. While Joplin is best known for his lively, toe-tapping ragtime classics like the “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer,” he also penned three works for the stage, including 1911’s Treemonisha.

But he never lived to see a full staging of that work. He paid for the score’s publication and a modest concert version in Harlem, cutting his already huge expenses by playing the piano accompaniment himself. Unfortunately, that premiere left audiences and potential investors underwhelmed; it also nearly bankrupted the composer. His score and libretto were essentially lost until the 1970s, when it received its world premiere at Atlanta’s Morehouse College.

And so this Volcano Theatre production, presented by TO Live and the Luminato Festival in association with a handful of other companies, feels like a major rediscovery. While the score remains largely intact, it’s been newly arranged and orchestrated by Jessie Montgomery and Jannina Norpoth; and the book and libretto have been effectively adapted by Leah-Simone Bowen and Cheryl L. Davis.

With these changes, the work — it’s being dubbed “a musical reimagining” — emerges as layered, profound, and urgently relevant.

In a brief prologue set in 1864 at a plantation near Texarkana, Arkansas, a young enslaved woman carrying a newborn child is being pursued by someone. She’s soon shot, but before she dies she secretly places her baby inside a hollowed-out tree.

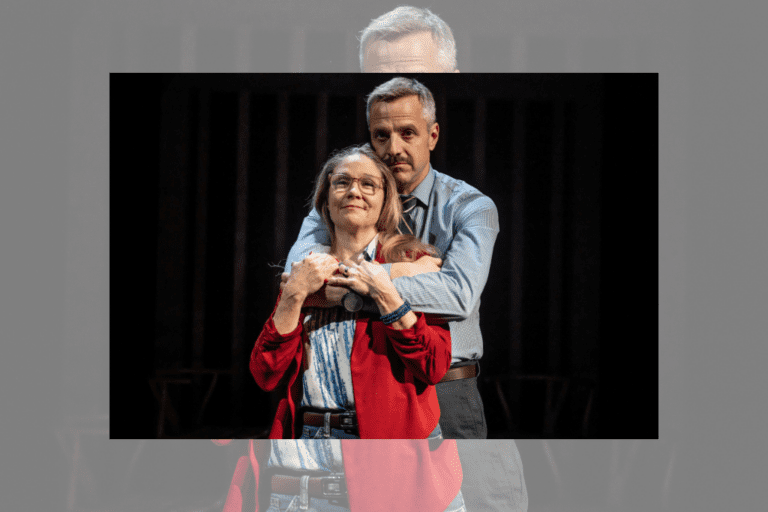

Twenty years later, that same child is now grown up and goes by the name of Treemonisha (Neema Bickersteth). Raised by Ned (Nicholas Davis) and Monisha (Andrea Baker) among a group of upwardly mobile Black folks called the Freedmen (slavery was abolished in 1865), she’s the first in her community to attend college.

She’s just about to be married to an upstanding — if rather dull — man named Remus (Ashley Faatoalia). But when she discovers that her parents aren’t her parents, and also realizes she doesn’t love Remus, she calls off the wedding and sets out on a journey to discover her real roots. She believes the answer lies in a group of nearby forest-dwellers called the Maroons, whom the Freedmen fear because of their Hoodoo beliefs and customs.

Joplin’s score encompasses a wide range of colours and moods. It’s misleading to call this a ragtime opera, although in many sequences you can feel the familiar syncopated rhythms of one of the earliest incarnations of jazz.

Montgomery and Norpoth’s orchestrations suggest everything from classical and gospel to Calypso and blues. Conducting an orchestra that includes both European and African instruments, Kalena Bovell brings out the rich textures and sounds that evoke the two strands of this milieu — the world of the Freedmen, who have been influenced by colonial customs, and the Maroons, who live a life more tied to the land and sea.

That contrast also emerges in the colourful costumes (by Nadine Grant) and sets (by Camellia Koo) that fill up director Weyni Mengesha’s fresh and lively staging.

While there’s occasionally an episodic feel to the opera, especially in the second act, Mengesha makes sure we always know where we are and what’s at stake for Treemonisha and the two groups of people she’s caught between.

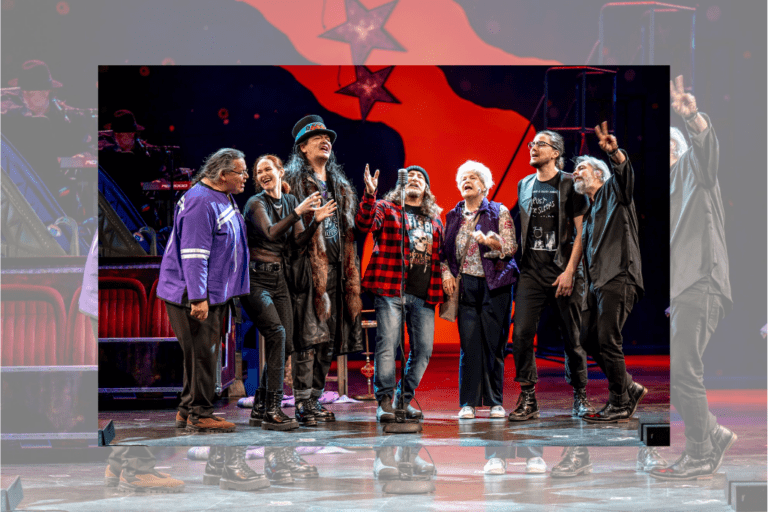

One of the highlights is an amusing Act One revival scene, played for comic relief, in which the extroverted and accurately named Pastor Alltalk (Marvin Lowe) “heals” members of his congregation. This scene gets a sombre variation in the second act when the Pastor’s opposite number, the Maroon leader Nana Buluku (SATE), mourns one of their fallen.

Each one of choreographer Esie Mensah’s dance numbers tells us a lot about the characters and helps mix up the opera’s rhythms. (The same can’t always be said of Western opera dance sequences.)

The opera’s supporting characters are carefully defined, although their dynamics are uneven. Baker’s Monisha, Lowe’s Pastor, and Faatoalia’s Remus practically raise the roof of the Bluma Appel, while Davis’s Ned and Cedric Berry – who plays a mysterious figure who first introduces Treemonisha to the Maroon – are a little subtler. Kristin Renee Young, meanwhile, is enchanting as Treemonisha’s sympathetic sister Lucy.

But it’s Bickersteth, involved in this production for the seven years it’s been in development, who emerges as the piece’s natural leader. Gifted with a clear, bright soprano that soars over the orchestra in a series of arias, and conflicted by the choices she has to make, Bickersteth is so effective she makes you think of all the iconic characters in operatic repertoire.

Joplin, at long last, belongs in the company of their composers, too.

Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha runs at the Bluma Appel Theatre through June 17. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments