REVIEW: A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay About the Death of Walt Disney ‘cuts to’ the core of the man behind the mouse

Upon entering the auditorium for Soulpepper Theatre and Outside the March (OtM)’s latest co-production, Heidi Chan’s pre-show soundscape treats the audience to a familiarly silly symphony. The song comes from Disney’s 1928 short film, Steamboat Willie. The iconic screen debut of Mickey Mouse made headlines earlier this year after the animation giant finally lost its decades-long battle to retain ownership over one of its most lucrative and brand-defining pieces of intellectual property. No matter how hard one may try, nobody can own a story forever, let alone control how it will be told by others.

Therein lies the essence of Lucas Hnath’s A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay About the Death of Walt Disney. As the title suggests, Walt Disney (Diego Matamoros) has penned an autothanatographical screenplay, which he’s now presenting to members of his family. Written in deliberately choppy speech patterns, and skilfully directed by Mitchell Cushman, it follows Walt’s struggle to conquer death through any means necessary: a spotless personal reputation, a namesake grandchild and company that will outlive him, a city made in his own image, pull-quotes from dictators who’ve praised his films, and a last-ditch effort to transcend his vulnerable fleshy vessel through cryonic preservation of his remains.

Framing his story as a screenplay allows Walt to focus the audience’s gaze through a curated selection of verbal tableaus. Among the script’s most inventive devices, Walt manipulates every scene by blurting out “cut to” whenever he doesn’t want to hear what somebody has to say to him. The excessive cutting gives the resultant dialogue the janky quality of an obviously doctored image, clumsily drawing attention to the very things he’s trying to conceal.

The media narrative surrounding this production has inescapably been shaped by it being one of Hnath’s two Toronto-premieres this spring. Those who were introduced to his work through Crow’s Theatre’s production of Dana H. will have seen an exemplar of his recent dabblings with pre-recorded audio. By contrast, Public/Disney serves as a foray into his more idiosyncratic early playwriting style, showcasing his structural dexterity, searing wit, and deep compassion for absurd figures. Hnath himself grew up in Orlando, Florida, and has said in interviews that his childhood proximity to theme parks was likely his first encounter with theatre, solidifying his lifelong love affair with the magic of artifice. It’s only natural that he should write a play about the veritable king of make-believe.

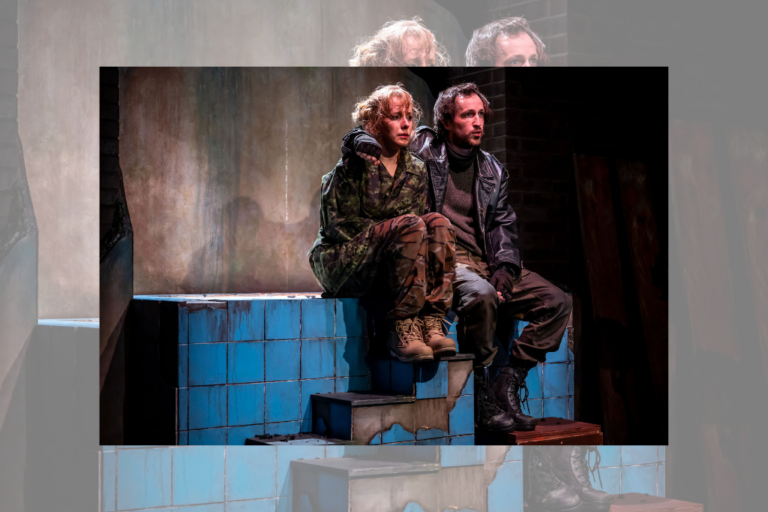

When you wish upon an all-star cast, your dreams come true. Matamoros commands the stage (figuratively and literally), embodying a mythic figure who’s secretly all-too-human. He smokes constantly, punctuating certain lines with hacking coughs and cancerous spurts of blood. At one point, he even pulls a string of bloodied handkerchiefs out of his pocket, like a magician performing at the world’s saddest children’s birthday party. The key to his performance is that it both is and is not a parody, bringing much needed pathos to a man whose life was defined by all things cartoonish.

Contrary to what Walt’s geodesic-dome-sized ego might have you believe, he’s not alone onstage. Anand Rajaram dazzles as Walt’s brother Roy. At the risk of being typecast as sycophants who do everything in their power to remain chortling at the antagonist’s right-hand — a hit that he’s pulled off expertly as Waffles in Uncle Vanya and a spineless colonial administrator in A Poem for Rabia — Rajaram’s casting here is a revelation. Roy is far more of a foil than a lackey, and hardly the pushover one might at first peg him to be. Rounding out the cast is a symbolic marriage of the two producing companies, with OtM mainstay Katherine Cullen and Soulpepper’s latest MVP Tony Ofori, playing Walt’s daughter and son-in-law, respectively.

For a piece with “unproduced” in the name, this current iteration at times feels somewhat overproduced. Since this particular text evokes the stripped down musings of a lonely buzzard cantankerously alienating everyone he knows on his way to the grave, it begs the question of whether the material necessarily needs to be treated with such operatic grandeur.

OtM has built its reputation on immersive works in unconventional spaces. Though Public/Disney is very much theatre within the walls, it reconfigures the typically-proscenium Baillie stage into a theatre-in-the-round setup. Helping to facilitate these multiple sightlines is the centrepiece of Anahita Dehbonehie’s set design: a Les Mis-esque turntable. Pragmatically, this keeps the action from becoming static and ensures that faces can be seen on all sides without requiring unmotivated pacing across the boards. At Walt’s end of the boardroom table is a control panel, suggesting that he personally operates the lights, sounds, and speed of rotation. Like his very own Carousel of Progress, it’s yet another way he tries to subdue the world to his whims, keeping himself firmly at the centre of everybody’s orbit. Turntables are also prominently featured as harbingers of death in a particularly gruesome plot point, lending the mise-en-scène an even more ominous texture.

Another standout of its scenography is Nick Blais’s mood-ring lighting design, snapping between sharp changes in colour palette in accordance with Walt’s moment-to-moment mental state. The best use of this convention comes whenever he discusses freezing his own head to be revived in a great big beautiful tomorrow, during which a cool blue light draws the eye to an illuminated ice block that otherwise sits inconspicuously on an office bar cart. As an homage to the ludicrous (albeit apocryphal) measures Walt takes to live forever, the degree to which the sweaty lump of coolant gradually melts before our eyes should not go unnoticed.

Hnath and Cushman effectively drown Uncle Walt’s highly manicured public image in acetone, leaving the audience with a grotesque portrait that feels at once comically exaggerated and painfully accurate. Disney may have lost the power to tell his own story, but it’s found its way into more capable hands.

A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay About the Death of Walt Disney runs at Soulpepper Theatre until May 12. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments