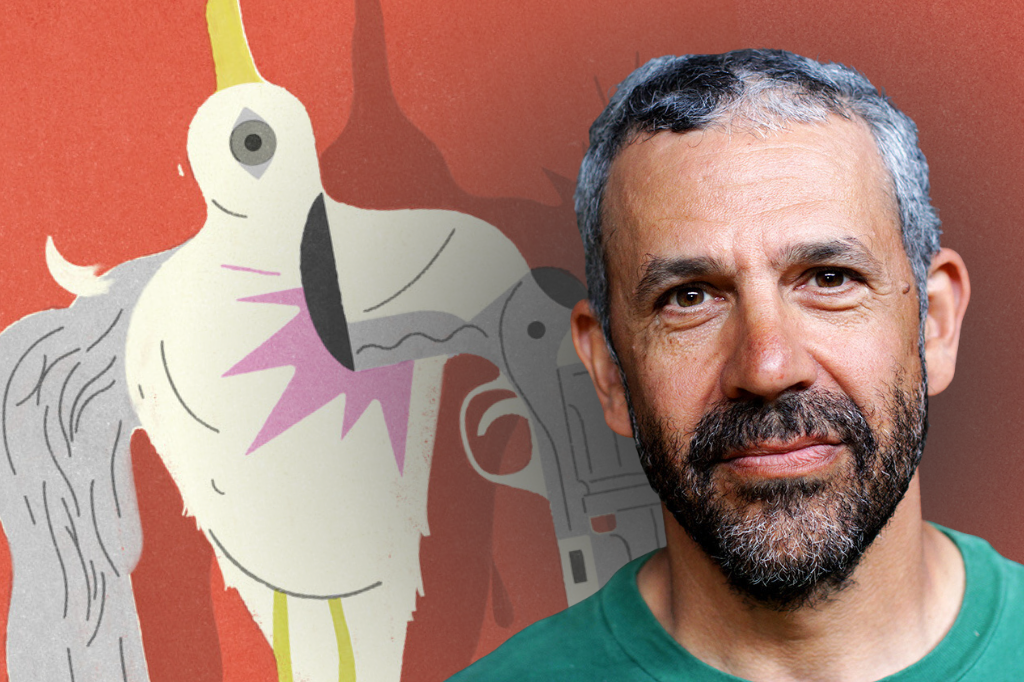

Laying The Seagull at Soulpepper’s Feet: In Conversation With Daniel Brooks

It’s become something of a cliché to point out that Chekhov is currently having a moment in the sun here in Toronto.

Between Uncle Vanya at Crow’s, Three Sisters co-produced by Hart House and the Howland Company, and the aptly named Chekhov Collective’s resurrection of the lesser-known The Fiancée at Red Sandcastle last month, local fans of the doctor-turned-writer have lately had ample opportunity to see him turn his surgeon’s scalpel toward the human condition.

I’m far from the first to point out that the drudgery of lockdown has created the perfect conditions for what some might call a resurgence of Chekhov’s relatability. His characters so often find themselves sitting around aimlessly, feeling time slip through their fingers, struggling to find meaning for their lives, without even the luxury of something as concrete as a “Godot” to wait for.

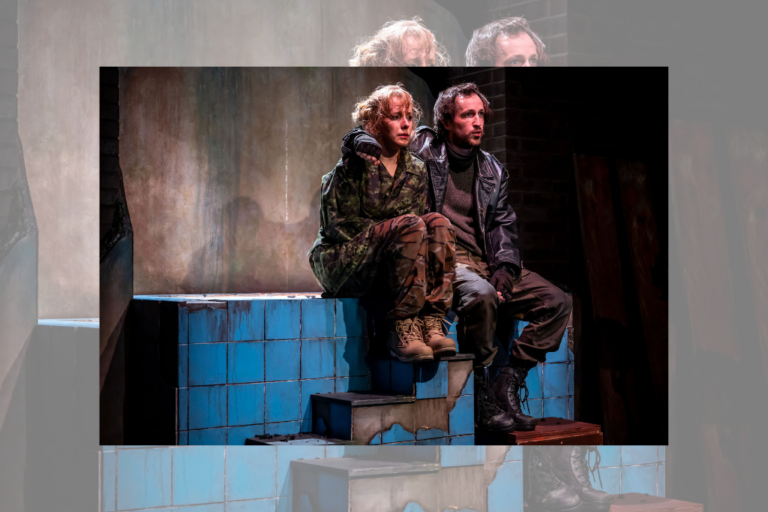

Soulpepper’s production of The Seagull was originally scheduled to open in late March of 2020. But as far as metaphors go, postponing a Chekhov production because we were all trapped in our homes, wistfully longing for better days, feels almost too on the nose.

Finally, three years later, The Seagull has landed in the Distillery District.

Canadian theatre legend Daniel Brooks, helming this production as director, is thrilled to see this long-awaited piece take the stage. “It was a very productive, creative, and joyous rehearsal period,” said Brooks in an interview, applauding the efforts of his “focused, talented, and hardworking cast.”

“I think we have some great stuff going,” he added.

Of the cast, only five of the actors contracted for the 2020 run have returned for this iteration, resulting in completely new dynamics and character pairings that have helped keep the work fresh. “Years have passed, which provides time to digest the play even more,” said Brooks. “The world changes, all of our individual circumstances change. So it sort of pushes the approach and the thinking around the play in different directions, which I find really interesting.”

During the height of the pandemic, Soulpepper attempted to salvage the unceremoniously waylaid production by including it as part of Around the World in 80 Plays, their series of audio dramas representing a diverse array of dramatic works from around the globe. As comforting as it may have been to have something creative to do during those #StrangeAndUnprecedented times, Brooks considered it to be only “a minor exercise,” far from capturing the magic of the in-person experience that had been lost.

“Chekhov’s plays, to me, don’t really translate that well to a purely audio experience,” he remarked. “All of the emotion and body and time that we had explored in our original rehearsal process, I kind of had to filter out — I won’t say flatten it — but it became more of a reading.”

Brooks, of course, is no stranger to Chekhov, describing himself as having “been a fan and a student of his for some time.” He added he’s used the playwright as a teaching tool “quite often” over the years.

That fondness began when Brooks acted in a production of The Cherry Orchard while still in university, and longtime patrons of Soulpepper might recall that he directed their production of the same in 2010. Yet, despite this intimacy, he also expressed some mild trepidations about tackling The Seagull, which he described in our interview as the “messiest” of Chekhov’s four major plays.

Brooks noted that, at this turning point in Chekhov’s playwriting career, “he hasn’t entirely worked out this new dramaturgy that he has more or less invented. So, for instance, in The Seagull, there are some old conventions that he uses; there are asides, and monologues, and it’s a little more wild in its form. At first, that really caused me some consternation. The more that I got involved with the play, the more I enjoyed its quirkiness and messiness.” Learning to embrace the mess, the imperfections, the cracks, and the unwieldiness was essential for Brooks to fall in love with the piece.

Soulpepper’s production uses a fairly recent adaptation of the text, written by the British playwright Simon Stephens, which premiered at London’s Lyric Hammersmith Theatre in 2017. Something Brooks especially appreciates about this version is its irreverent attitude toward what others might view as the sanctity of the original. He drew special attention to how the play’s famous opening line has been altered — originally “Why do you always wear black?” now rendered by Stephens as “Why do you do that? […] Wander round like that? […] You look so angry. All the time.” — which Brooks sees as “an interesting signal to the Chekhov-purist that they should relax a bit.”

One of the characteristic features of Stephens’ version is that it completely de-Russifies the text, which certainly feels like an ideal way of handling a distinctly Russian piece in our present moment. Despite Chekhov being an author for whom global audiences are eager to describe as “universal,” it’s hard to deny that so much of his works are quite particular to the historical conditions of their 19th century Russian context. Brooks is highly attuned to how this factor “presents the modern performance dilemma.”

This brings us to the elephant (or bear) in the room that hangs over any discussion about Chekhov being so prominently featured in Canadian theatre right now, as voiced in Andrew Kushnir’s recent viral essay on the tension between Russian cultural ubiquity and the war being waged in Ukraine.

Brooks brought up Kushnir’s article in our conversation before I even had a chance to tactfully enquire if he’d read it.

He acknowledged, “I probably would have read the article differently if I weren’t in the middle of rehearsal of a Chekhov play.”

Without having the article fresh in his mind, and with no desire to offer anything like a rebuttal, he had one nugget of insight to offer. With reference to Kushnir’s underlying belief that “it’s in theatre’s essence to engage with the Now”, Brooks had this to say: “I actually think that that can be true, and also not true. That is something that one theatre artist may utterly embrace for an entire career, but for me right now, I actually feel the opposite. I don’t feel the opposite as a truism, I just feel the opposite as in I feel so saturated in the moment, in the politics of the moment, in the language around all the politics of the moment. It’s around us all the time. And I actually look to the theatre to bring me into a broader, perhaps mythical perspective, something that actually takes me away from the moment, for a moment. Not escapism — perspective. Perspective and expansion, so that I can actually see the moment more clearly.”

Time will tell if Russian plays begin to take a backseat in the coming years, and if Canadian venues will make a conscious effort to tell more Ukrainian stories in their place. Soulpepper’s production of The Seagull was conceived well before the invasion on February 24, 2022, and is now finally being received by an audience of individuals whose minds are swirling with discourse the company couldn’t have anticipated in 2020. Whatever the future of our theatrical landscape might have in store, perhaps there is room for us all to see the messiness of this moment a little more clearly, if only for a moment.

The Seagull runs at Soulpepper from April 13-30. Tickets are available here.

Comments