REVIEW: We Quit Theatre challenges existing narratives in its exploration of autofiction

Theatre “collections,” more than a set of works in a season but less than a deliberate trilogy, are an interesting proposition for a reviewer. These separate works that have been drawn together but can also be seen apart invite a thought process about shared theme and purpose. Gislina Patterson and Dasha Plett, the forces behind We Quit Theatre, recently brought a trio of works to Buddies in Bad Times, each presented twice within a week.

In 805-4821, Plett uses a projector and near silence to present a sort of living poem that explores questions of identity, trauma, and the media that shapes us. In i am your spaniel, Or, A Midsummer Night’s Dream By William Shakespeare By Gislina Patterson, Patterson uses the premise of textual analysis to actually deconstruct everything from gender roles to land ownership to class warfare. And Passion Play teams the two up for a set of “improvised erotic retellings of Bible stories” with the moody feeling of a séance where the only thing resurrected are stories.

Ultimately, all three performances tell and retell stories via intriguing formats to challenge old narratives and structures, making the most of the “autofiction” (autobiographic fiction) genre. The opposite of “quiet quitting,” this collection makes a joyful noise — and I don’t think anyone would want its creators to resign.

805-4821: Are you picking up what I’m projecting?

In 805-4821, Plett’s history of her collaboration with Patterson is performed via an overhead projector that brings back memories of a pre-Google and YouTube classroom (during COVID, the play was also adapted into a live-typed Google Docs version for online viewing). The audience can simultaneously watch Plett silently feeding her poetic text through the projector and the text itself on a large screen overhead, as it’s uncovered line by line in real time:

Dear Mom,

On October 10, 2018,

a Wednesday,

you came to my apartment.

You brought me cookies.

I said, I’m not sure how comfortable I am

visiting home right now.

I know that hurt you.

It hurt me, too.

I wish this movie

wasn’t about us.

The “movie” Plett refers to is a sort of metanarrative where she views her story from the outside, showing it to us as a presenter while she experiences her own words about her correspondence with Patterson, their bonding over a production of Hamlet, her coming-out story as a trans woman and its impact on her relationships with her family, and a traumatic story of abuse at the hands of a family friend, a salt-of-the-earth female swim instructor.

In recounting these moments, Plett sometimes refers to herself as Hamlet, seeing their similarities and placing herself in another story filled with the voices of ghosts. In one of the show’s most charming moments, representing herself a voyeur to her own experience, she even stops for “Popcorn Time!”, microwaving a bag on stage and consuming the whole thing while another section plays without the intervention of her hands. Visual support comes in the form of short film GIFs that break up the poetry and remind us that the funding for the show initially came from a government grant exploring the golden age of silent films.

805-4821 is a portrait of coming-of-age yearning so sharp it hurts, and it’s likely to spur some of your own memories as well, while being a reminder that transness often results in a second, later coming of age. It’s a study in silence and the way it forces you to pay attention, especially in the way it makes you sit in silence with a fellow audience of strangers, a naturally uncomfortable act. It’s literary and wise and a bit silly, too, comfortable in its own moments of pretension. While talking about her swimming lessons, Plett broadcasts footage from an inviting but chilly-looking body of water: life’s a beach, the play implies, but also, life’s a beach, and then you die.

On the evening I viewed the show, Plett’s performance preceded a 45-minute excerpt of a “response” in the form of Sadie Berlin’s Enchantment Island: This Alien Nation, which examined Berlin’s experience as a fat Black woman in a world hostile to both. Berlin created a fascinating portrait of a future, post-revolution Toronto, as well as a look into her past as a triumphant runner despite the disbelief of her classmates and the abuse of her mother. This response covered similar themes of identity and oppression, but ultimately felt less like a direct response and more like a style homage, using projections of text, along with an entertaining sequence where Berlin literally chews up and spits out the pages of works like the Bible, the complete works of Shakespeare, and the Harry Potter series.

i am your spaniel, Or, A Midsummer Night’s Dream By William Shakespeare By Gislina Patterson: Bard with Bark and Bite

Forgive me a digression, but speaking of autobiographical Shakespeare stories: when I was 19 years old, I was almost killed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream. A falling stage light during rehearsal for a Harlem production of Shakespeare’s daffy fools-in-love comedy, for which I was an intern, walloped me in the head and might have broken my spine if I’d been less lucky. The near-miss with paralysis instead strengthened my metaphorical spine: I developed a healthy distrust of authority and the frankly abusive conditions under which a lot of theatre companies and institutions operate.

So I was baying for a good anarchical time at the start of i am your spaniel, which delivers in spades its takedown of Midsummer, Shakespeare’s most-produced play. Theatre artist Gislina Patterson, in true meta fashion playing a slightly-cooler “drag” version of themselves as academic Gislina Patterson (the stage persona uses she/they pronouns, where the actor uses he/they), begins with a juicy bone to the Shakespeare scholar.

This semi-real, semi-faux lecture starts with a close reading of text, looking at the Bard’s original First Folio edition with its unusual spellings, punctuation, and line length. Actors collected most of the text of the Folio, so the choices made suggest potential readings of their purpose for the performers.

Patterson accompanies this exploration with projections that highlight the pertinent moments, looking at words that have been condensed and words that have been elongated, focusing on the way these small textual flourishes add meaning and are ripe for interpretation. Each technique has its own signature sound effect, leading to a synthwave Shakespearean symphony as we parse the text, reminding us that language is its own music. Patterson then reenacts the play briefly to make sure everyone knows the plot, entertainingly using various convenience store drinks and snacks on their realistically crowded, messy desk to represent the characters.

However, this is not just a Shakespeare class, as we learn the second Patterson projects a male scholar’s footnote onto the screen, vehemently disagreeing with the man’s dismissive discourse about the role of women and how it pertains to the play. Patterson goes whole hog…or, rather, dog, into a complex spiral of memory and history. The play becomes less of a treatise on Shakespeare and more of a patchwork quilt of digressions; you’re never quite sure how Patterson is going to pull it all together, but it works as a tempest (whoops–wrong play) of smart, sharp observations that devolve into absolute chaos.

We learn Patterson’s own story of becoming a literal poster child for the future of possibility of becoming whoever you want to be in Winnipeg while the hopes of a generation are instead sold to developers, a failed anti-landlord crusade from Shakespeare’s time, and the Bard’s own role in that story as an agent of capitalism. Ownership remains paramount in these discussions: ownership of land, identity, climate, gender, work, self-respect, time, the future.

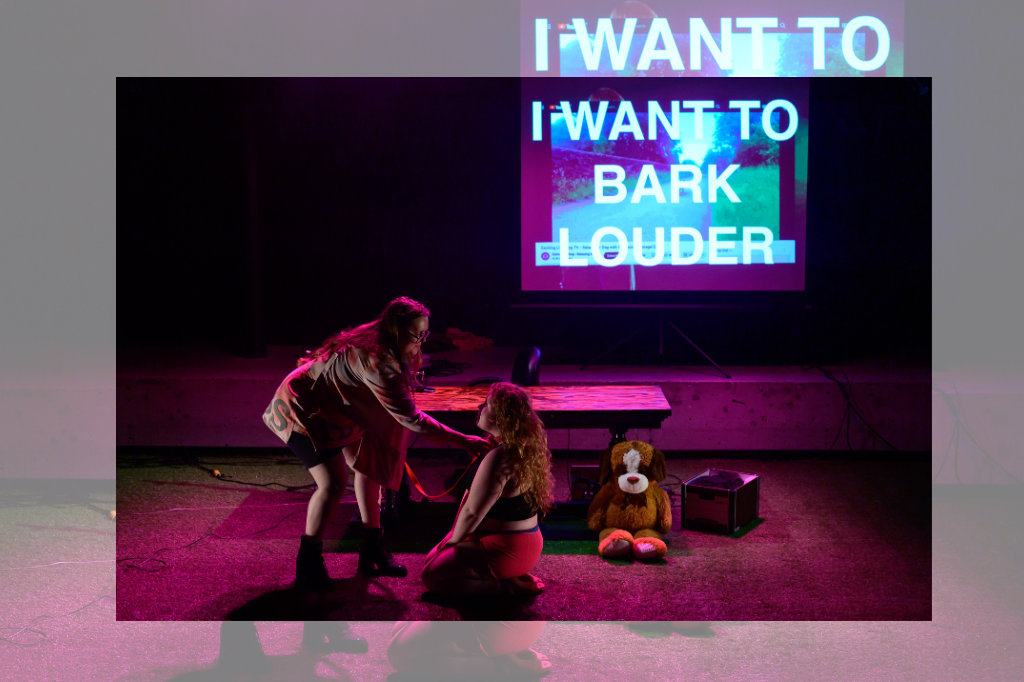

In Midsummer, “I am your spaniel” is the hapless Helena’s line, as she exhorts her crush Demetrius to “use me but as you use your spaniel— spurn me, strike me, neglect me, lose me.” Slowly morphing into said spaniel, complete with lolling tongue and collar, panting and rolling at the feet of an invisible “master,” Patterson’s “unleashed” performance intriguingly presents the seductive freedom of either complete surrender to society’s pressures or of opting out of them entirely. The freewheeling discussion can get a little scattered at times, but the volume of thoughtful ideas, Patterson’s committed performance, and the quirky DIY set contribute to an electric, captivating 90-minute performance.

Passion Play: The New Testament, Remixed and Rated R

At the end of the week of exciting theatrical experiments, the only untested world premiere, Passion Play, ends things with more of a whimper than the promised bang. Passion Play’s premise is to deliver “improvised… erotic retellings of New Testament Bible stories” that Plett and Patterson have also turned into a linocut book. In the performed version, it’s not entirely clear which aspects are fixed and which are made up on the spot. Plett and Patterson create an admirably moody atmosphere, dimming the lights and highlighting flickering candles in a clear Plexiglass box between them, like they’re performing in a small occult shop on Queen Street West.

It feels like a séance or at least a summoning; you’d be forgiven for envisioning a theremin playing over their outstretched hands, though the sound is more of a low growl. After the initial rumbling, we hear a recording of an original biblical text, to which one performer responds with an extended story, “committed to recording” on tape as it’s told. The evening I saw the show, we heard two stories. One was about two different groups of close female friends working in marine biology, one group of which has a much better work ethic than the other and is therefore as a group handsomely rewarded sexually and with impressive stamina by their hunky supervisor while the others are shut out of the turn-based orgy; the other (which was interesting, but not especially erotic) involved a story of trust and live burial.

While I appreciated the premise and the mood of the proceedings, the quiet, sometimes monotone nature of the storytelling sometimes made the tales less easy to follow than they could have been, especially as an audience member not steeped in Christian dogma.

Part of the fun of improv is fully knowing the rules of the game and how the improviser is using them. With only a loose structure bringing the audience into the game as an improvisation, and the performers facing and telling the stories primarily to each other rather than the audience, it was hard to engage with the texts as improvisations. It was also unclear whether the stories were also in the book, retellings from previous improvisations, or were being improvised fully in the moment.

This was particularly true because each artist only told one story, separate from the other story being told. Since the other two shows thrived so spectacularly on their lightning-quick connections between ideas, here it seems like things are only starting to get going when the proceedings conclude. It’s a fascinating concept, and I can see it really coming into its own the more it’s developed and presented.

If there’s one thing We Quit Theatre shows through this anthology, it’s a sense of fearless action in the face of the intense fear of our current world, a willingness to throw caution to the winds in experimenting with form and function to deconstruct the classics while looking to the future. My advice? Don’t quit while you’re still ahead.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments