REVIEW: Coal Mine’s Fulfillment Centre asks how we end up alone, together

In the eponymous New Mexico warehouse at the centre of Coal Mine Theatre’s Fulfillment Centre, floor manager Alex (Emilio Vieira), reading robotically from a company script, introduces has-been folk singer Suzan (Kristen Thomson) to her new job sorting the “holiday dreams come true” contained in the endless rows of cardboard.

This promise of delivered dreams casts an ironic twinge over U.S. playwright Abe Koogler’s exploration of isolation in contemporary America, while also placing the play in the Die Hard pantheon of “technically a holiday story.” The drama follows four blue-collar everybodies lost in the desert of a small town surrounding the warehouse, desperately searching for fulfillment from each other, like the kind supposedly promised in those boxes.

Desperation is the thread that connects Koogler’s characters. Suzan needs a job from Alex so she can fix her car to go settle with a former flame in Maine. Alex is desperate to deliver for his higher-ups and prove to girlfriend Madeleine (Gita Miller) that the move from New York was worth it. Madeleine, resenting the migration and desperate for excitement among the tumbleweeds, arranges a date with John (Evan Buliung), an enigmatically mumbly carpenter living out of his car after a mysterious breakup. Suzan, camped out near John and vying for him to drive her north, probes him for a desperation to which she can offer the solution of her company.

Beyond the setup of each relationship’s conditions, Koogler’s script eschews much plot development, instead focusing on character studies of budding connections interrupted by transactionality. Tender moments like a job orientation turned stress-release ritual between Alex and Suzan toughen through the professional power imbalance one holds over the other. John, at first a quietly earnest ear for Suzan and Madeleine, holds sinister, simmering expectations of what listening to others affords him. In Fulfillment Centre, kindness is never unconditional.

Nick Blais’ set places characters in a cardboard playground, with boxes that modulate Transformer-like to become restaurant tables or cars; it’s both slick to watch and drives home the cheap materialism these people are stuck servicing. Overall, the space evokes a giant stationary conveyor belt, suggesting those upon it as just four more in the endless procession of packages — destined for dissonant destinations, all in some way a product to someone else. It’s a Catch-22 appraisal of the loneliness epidemic; these outcasts yearn deeply for connection, yet find it debilitatingly terrifying to enact. Wielding grand gestures, substances, or sex as stand-ins for deeper relationships, no one can make it through a genuine conversation without crumbling into anxious confrontation.

The ensemble rides an impressively unified undercurrent of anxiousness, creating a shared language of nervous laughs, awkward intimacy, and dropped sentences that depict the atmosphere of isolation as a shared infection between them. Thomson and Buliung in particular offer expansive depictions of how loneliness manifests; Thomson with a panicked people-pleasing chipperness, always on a knife’s edge, Buliung with a quietness he clings to as a means of suppressing anger at the world he feels left out of. Both drip with grief for better pasts.

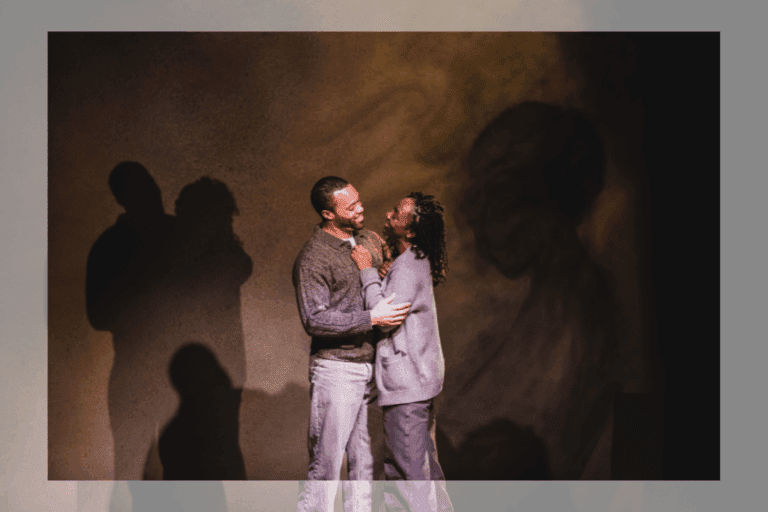

The production as a whole latches onto the exciting tension of missed connections. Director Ted Dykstra often has actors turn their backs to each other, letting us watch the shifts in characters’ faces when they look out to the audience, like non-verbal asides. Blais, also lighting designer, often isolates the actors’ upper bodies or casts stark shadows over their expressions, with an LED grid in the floor creating lines in the New Mexico sand, evoking the characters’ emotional barriers.

The production understands the play’s themes, yet feels limited by a script that delivers a package it never fully opens. After 90 minutes of repetitively revealing how broken and alone they are, everyone ends up either quietly accepting their unhappiness, or finding themselves stranded on literal and/or metaphorical roadsides. If Koogler is asking whether loneliness is inevitable, it feels like a leading question never posed with much variation, leaving little room for the audience to consider the answer for themselves. Coal Mine’s thrust seating arrangement invites fleeting eye contact with fellow audience members across the way; considering the script’s appraisal of chance encounters leans into the pessimistic, I wondered if there was opportunity for Dykstra to complicate this thematic exploration by taking further advantage of the act of gathering that live theatre offers.

The play’s final moment offers the faintest glimmer of hope in a phone call Suzan has spent the play afraid to make. While your product review of Fulfillment Centre may depend on your tolerance for its cynicism, I left with an appreciation for the close ones in my life who keep loneliness at bay. With performance and design finely tuned to the play’s themes, Coal Mine’s production is still worth placing an order to witness.

Fulfillment Centre runs at Coal Mine until December 7. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments