Essential Work

Two weeks before opening night, I crawl on my knees under the tangle of cables to get to my microphone. It’s a tight squeeze and I have to keep my arms close to my body so as not to tip over a table or my vocal processor.

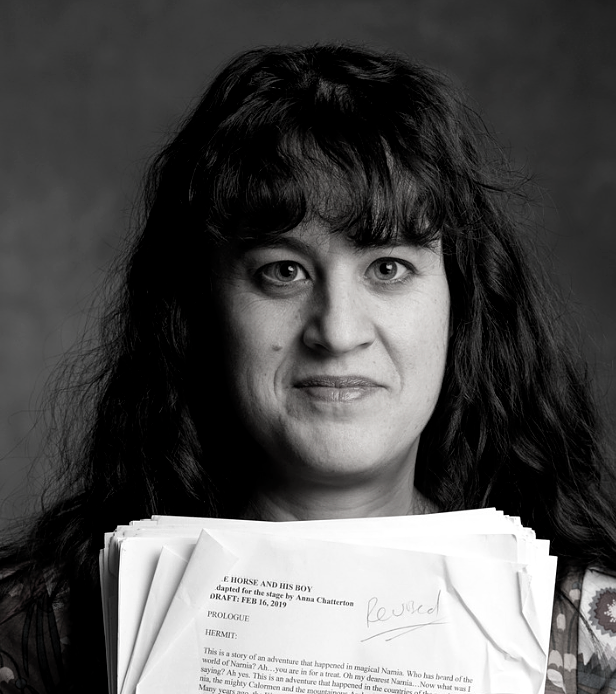

I am rehearsing my solo show Quiver in my small home office, crowded by a set of three bar tables of varying size and all of my sound and tech gear squashed between my desk and my blue couch. My play tells the story of a single mother and her two teenage daughters as they endure an event that splits the family apart. My director, Andrea Donaldson, lives in Toronto and doesn’t feel comfortable rehearsing together in a room, so we rehearse via Zoom. But in order to get my sound across properly, we have to use two computers and set up a video camera on a tripod in front of my mic. During the 70-minute run, I shift my eyes between the camera and an imagined future audience through the doorway to my living room.

I was originally supposed to tour Quiver to three small towns – Kitchener, Fergus and Waterford – in September 2020. When the pandemic hit and four other productions of mine were cancelled, I assumed the tour was off, too.

I kept playing it in my head: another one bites the dust.

I had trouble accepting the fact that theatre was now considered non-essential, and went down a dark rabbit hole of questioning all of my life choices: why did I devote my life to theatre? Why didn’t I prioritize making a comfortable living with a pension? Why didn’t I go to medical school? Or get my PhD? That wasn’t new, of course – invariably, every few years, I question my choice of stubbornly sticking out a life in theatre. But this feeling was different, darker, more urgent, more soul-searching, and ultimately, more depressing.

I kept playing it in my head: another one bites the dust.

I wrestled with these questions for months. Then, in July, Claire Senko, the artistic producer of Old Town Hall in Waterdown, texted me to see if we could have a phone call about still doing Quiver in the fall. She carefully talked me through all the precautions her venue would be taking, including keeping windows open, making use of a good ventilation system, enforcing mandatory masks, staggered audience entry, and contact tracing, and grouping seats by households in socially distanced chairs. The clincher: Waterford had no cases in their town. I emailed my stage manager, who said she would consider it and initially said yes, but when they added a fourth show in Waterford to make the tour more economically viable for us, she declined, citing her nervousness due to COVID-19. I hired Rick Banville, who lives in Hamilton and had lost most of his work due to the pandemic, and we had long discussions about the safety of doing the show, about whether schools might close again, about if there would be a second wave – we agreed we would ask for a clause in the contract that we would be paid half our fee upfront in case the show was canceled.

It’s 7 PM, an hour before curtain. Rick and I are the only ones in the theatre. I take off my mask to test the sound, and feel very strange; it’s the only time since March I’ve been indoors without a mask around someone from outside my household. Normally the theatre opens the doors a half hour before showtime, but this time they’ve shortened it to ten minutes. Before the audience comes in, I station myself on stage and start my prelude soundscape, a compilation of sound effects and music which I DJ, punctuated by live singing loops. Slowly, people start to trickle in. Each night the theatre puts name labels on the chairs, and masked volunteers lead audiences to their assigned seats . The room is set up with groups of chairs, some two, some three – one even has a table with five. It looks like an odd furniture store, with an eclectic collection of little wooden tables for people to put their drinks.

The audience members don’t seem to be talking to each other; they’re all just sitting and staring at me. I’m on a raised stage, about fifteen feet from the front row. The conceit of being onstage pre-show is to have Anna (me!), the master of ceremonies, telling this story to an audience, so I wave and smile at people as they come in.

I can’t tell if they’re smiling back.

My neighbours arrive, though, and they wave back at me. And then it’s go time, and I perform to the sea of masks. People laugh, but not uproariously, not the way they have in previous runs of the play. Is it because it’s a small audience? Or because they’re all wearing masks? Or because it’s Thursday? COVID nerves? Impossible to know.

But when the show’s over, there’s an enthusiastic burst of applause that surprises me.

Normally, I come out from behind my microphone to bow, but we decided that it would make the audience feel anxious if I come too close to them, so I stay and bow behind my music stand and my microphone. I walk off as they’re still clapping. I stand in the dressing room and the loneliness that happens after doing a solo show creeps up. I get dressed, back into my warmup sweatpants. No fancy dress tonight.

When I go to the lobby, it’s just Claire and Rick and one of the volunteers left. Claire tells me that normally, on opening nights, champagne flows, and they usually put out a spread of food that somehow aligns with the show’s themes. I feel a moment of sadness for missing out on a fun party, but I console myself that it’s special that I get to perform during the pandemic when so few in our business can.

I console myself that it’s special that I get to perform during the pandemic when so few in our business can.

The next day, there’s an article in the Hamilton Spectator about an amateur live production of Little Shop of Horrors in Burlington, and how three of the cast members contracted COVID-19 during the production. Everyone is up in arms about it, though J. Kelly Nestruck tweets he would not draw large lessons from a community theatre production in Burlington. However, people in the theatre community post on social media that this is clear proof there shouldn’t be any live performances during the second wave of the pandemic. It makes me feel guilty and defensive, though mine is a solo show, and the three people who got COVID in Burlington were not audience members.

But I don’t feel like I can say anything in response… because I’m not scot-free yet. We’ll have to wait two weeks to really know.

Each night, as we drive the fifty-five minutes from Hamilton to Waterford, we venture into the most exquisite sunsets, deep reds, oranges, yellow, with black outlines of trees set against the burning sky. It’s breathtaking. The very act of driving towards doing a live show is uplifting and illicit and a new kind of exciting. Rick tells me the audience in the lobby before each show is tentative, but everyone makes an attempt at normalcy. Everyone seems eager to drink, to look at each other and talk, to look at the art for sale on the walls, wanting to participate in the “preshow in the lobby with drink in hand” experience they’ve so missed.

This second audience is more responsive, and it feels almost normal. Two of my friends have made the drive to Waterford and sit in the front row, texting me after to say what a great experience it was to sit with others and watch me perform – something so simple and yet so profound.

However, by the third day of the show, both Hamilton and Haldimand-Norfolk County have been put into the yellow zone of COVID-19 restrictions. I’m surprised to learn about Norfolk County, and feel a bit nervous. There are twenty-seven active cases in a county of twenty-seven thousand people.

Odds are low, but still, yellow…

A half hour later, Biden is elected in the United States. The sun is out, it’s an unusually warm fall day, and relief washes over me. I imagine that happiness will spread into the audience. But, as people come in that night, two audience members take off their masks when they sit down. They are an older couple, and look a bit defiant. I wonder if they are Trump supporters, but then – why would they come to this play?

It’s a full audience, yet it’s more work tonight, a more somber crowd. Rick and I wonder if it’s due to the yellow phase of COVID precautions. I am acutely aware of my spit tonight – a result of talking for seventy straight minutes. Rick tells me that I am two minutes slower tonight, which is fairly significant – it means the play might have had a more lethargic feel to it, a bit of a lag, not a breathless race forward. I’d slowed down all the characters in reaction to the lack of response in the audience.

The final night is the smallest with only fourteen people, but is the most responsive audience. They laugh throughout and give me a standing ovation. We strike the show in record time and pack the car. Claire lingers outside with us and tears up talking about the importance of live theatre during this time of intense isolation. And standing there, elated from the warm response that night and having actually done this run, something I had honestly secretly thought would most likely not happen, I realise: doing this show was an essential service for our health – not only for the audience, but for Rick and me as well.

Limbic resonance – the idea that the capacity for sharing deep emotional states arises from the limbic system of the brain.

Rick talks about limbic resonance – the idea that the capacity for sharing deep emotional states arises from the limbic system of the brain. That being together, in-person, creates connectivity and an energy exchange, one which promotes dopamine and feelings of empathetic harmony. This small solo show, in a tiny town, for an even tinier audience, feels huge and important in this moment. Rick talks about how I am an essential service provider, creating this experience for everyone. This idea resonates deeply with me, and I start to understand my depression earlier in the pandemic more acutely.

There is a necessity for theatre, a necessity that is real and true and pure and imperative.

This is not a huge revelation.

It is not new.

Theatre practitioners have always known this to be true, this necessity of our craft, but did we think of it as an essential service? I’m not sure I thought of it before in such terms. The pandemic sent us into turmoil, disconnected us, took away the essential person to person and collective connectivity. Now, as much of our country rests in a lockdown or red phase of pandemic restrictions, it feels like a dream that I performed to a live audience for four short precious days and left restored, rejuvenated and full of hope for the necessity of theatre.

Ten days after my show closes, it’s reported that a beloved costume designer from that Burlington community show died from COVID. The nightmare. What we’re all terrified of, what we’ve heard in news stories and in PSAs – happened. If it had occurred before our run of Quiver, would we have gone forward with it?

It’s now February, and Ontario’s on the brink of exiting its strictest lockdown since last March. Theatres across the country have closed, and we’re once more interrogating digital theatre – its merits, its capacity to replace that which we knew just a year ago. The live performance of Quiver seems a distant memory, a relic of the less suffocating weeks of COVID-19 restrictions. Almost like a miracle, Quiver was performed in the brief moment of time when it was possible.

There was a volunteer who came to the show each night – he didn’t have to, the theatre had many volunteers – but he told Claire that he needed to for his mental health.

I realise now: I needed it too. I needed to feel essential in this surreal time. I am not a doctor, I am not a health expert, I am not a therapist, but I am able to provide an escape to another world for seventy minutes.

That’s my essential service.

Comments