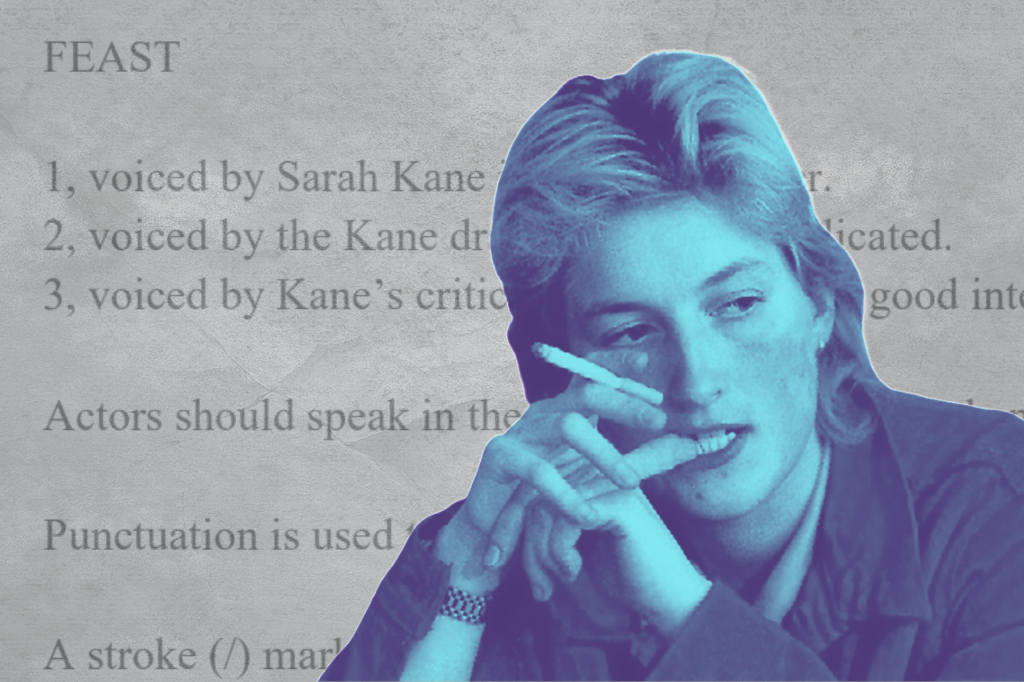

Sarah Kane’s Been Dead For 23 Years. I Still Don’t Know How to Thank Her.

Sarah,

The things I need to tell you. The things you can’t understand. The things you’ll never hear.

The twenty-third anniversary of your death was yesterday.

Toronto’s no longer a far-off daydream, it turns out: I live here, and I live here alone, save for the impish kitten-turned-cat named for a Sylvia Plath quote.

I always promised you I wouldn’t become a caricature of myself, a vapid proselyte, a two-dimensional dramaturg with reverence for little but angst: I don’t know if I’ve kept that promise. Fig’s name might be testament to that, and if you were here, you’d laugh, cigarette between teeth, extra light stretched towards and gratefully accepted by me (sorry, Mum, when you read this). If you were here, Fig would like you, I think, the tabby monster gnawing on my laptop charger as I write you this note. You’d pet her, and your eyes would flit towards bookcases groaning under the weight of Canadian plays — you’d notice the growing discrepancy between my Kane collection and the printed solo shows ordered from Playwrights Canada Press. You’d sense the change.

You’d notice the growing discrepancy between my Kane collection and the printed solo shows ordered from Playwrights Canada Press.

None of this will ever happen.

Bloor Street isn’t particularly long, it turns out — it’s a subway stop, a noisy injunction on trips downtown.

Tarragon Theatre is no longer mythic, no longer a shriek at the edges of my pre-COVID memories — it’s a theatre. It’s an email contact. It’s a building. It’s a feeling, a question, a glimmer, a cheque instead of a reading. It’s a theatre. I miss it. It’s a theatre.

Sarah: I’ve been planning this note for months, awaiting February the way a child awaits Easter. My letters to you are a once-a-year digestif, an acknowledgment of gratitude, of lineage, of love. When I first started thinking about what I wanted to say to you this year — what Toronto anecdotes you should hear, how my partner read your canon of work before our first date, that antidepressants are awful and wonderful and necessary and frustrating — Feast sat in a drawer. I didn’t think I’d need to update you on it: there was nothing left to say.

I was wrong.

Feast, my verbatim play about you and theatre criticism and me and our tangled legacies, was proof that I’d written, that we’d had this not-relationship, this courtship of unread letters and dramas. Feast was firmly rooted in a life in Ottawa, in a crisis averted, in a growing feeling of inadequacy and lostness. I couldn’t possibly commit to being a theatre critic full-time, Feast posited — there was too much work to do for that. Feast was finished.

And then it wasn’t.

Fuck. I’m working on Feast again. At the University of Toronto, a campus upon which I’ve still not set foot due to the pandemic. With Djanet Sears as my mentor, the playwright I’m still stunned I get to learn from once a week, if only over Zoom. I’m once more, in a classroom setting, placing my neuroses in dialogue with your prose, your interviews. I’m immersing myself in verbatim dramaturgy, in autoethnographic theory, in re-surfaced photos, in TikToks about you. I’m doing this again.

I’m sorry. I’m not. I don’t know.

I couldn’t possibly commit to being a theatre critic full-time, Feast posited — there was too much work to do for that.

I got my first fan letter this week.

Sarah, even I acknowledge how pretentious that sounds, how conceited and daft that sentence must seem in the ether between you and me. But it’s true — and it stings. Someone in another country, three time zones away, a stranger I’ll never meet, wants to know what set Feast into motion in 2019, how we got here, how I did it. Someone’s directing a university production of 4.48 Psychosis (time’s never felt more circular, the university productions of the play that changed my life, the friendships and battles that followed me and will surely follow the letter-writer). The letter-writer took time from their life to tell me how much Feast resonated with them; how grateful they were for the piece to act as a bridge between my generation and yours; how eerily the play sounds like Crave.

The praise made me numb. The questions gave me pause. The reflection on three years — three, whole, fucking years — between starting Feast and writing my third yearly letter to you made me nauseous, then melancholy.

It’s the kind of email I’d have written to you at age twenty. It’s the first draft of an email I’d write to you now, all tongue and no teeth, dripping with sweetness and with no critique in sight.

From my perch at the edge of age twenty-four, I think my thoughts towards you now are more balanced — the love’s still there, but it’s tempered with curiosity and amusement. You’ve changed my life: I feel I owe you more than childish adoration.

I owe you more than childish adoration.

Sarah: things are different. This life in Toronto is thrilling, and even beautiful. There are fewer landmines, fewer ghosts. With the move has come a promotion at Intermission, a new set of friends (including the one copyediting this note), a cat, a studio apartment, a Taylor Swift obsession, a change in hair colour and wardrobe. Some weight’s been gained back. The sleeve of tattoos on my arm is more crowded.

But I’m still working on fucking Feast.

Sarah: we’ve done this before.

And I’ve no reason to think we won’t do this again.

Until next year,

Aisling

Comments