Murder at Ackerton Manor pays homage to Agatha Christie with a puzzle box of laughs

“It’s Agatha Christie meets Mel Brooks.”

That’s playwright and director Steven Gallagher’s description of Murder at Ackerton Manor, a comedy homage to the mystery novels of Agatha Christie sure to leave audiences dying of laughter when it opens on June 12 at the Lighthouse Theatre in Port Dover.

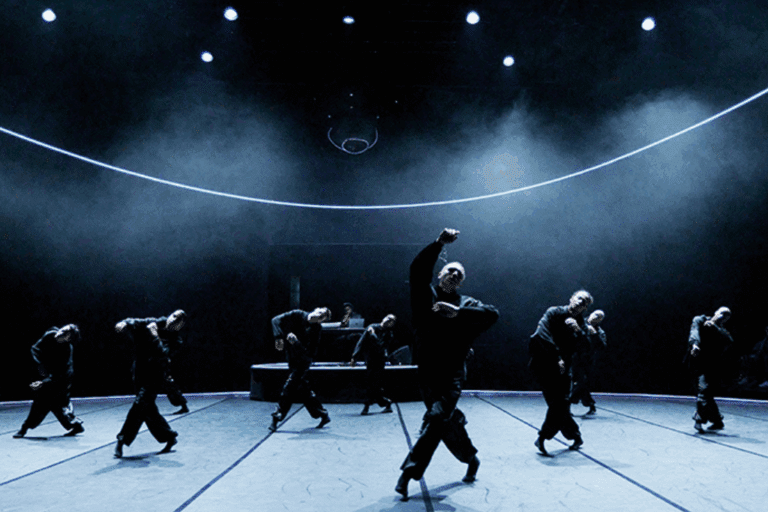

“It’s set in 1950 on a dark and stormy night in a remote mansion,” Gallagher explained in a Zoom interview. “Megan Cinel, our set designer, is so collaborative and such a brilliant young artist. She came up with this beautiful, Gothic English country home set that looks like somebody’s real [house]. The detective is a French-Belgian detective,” which Gallagher says is a reference to Christie’s iconic character Hercule Poirot.

“All the tropes are in there,” Gallagher assured. “There’s a German professor, a dowdy British monarchist, a Southern belle.” Naturally, a murder ensues, and the culprit must be found.

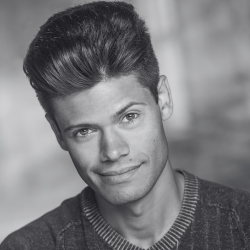

Step aside, Kenneth Branagh — Ackerton Manor is far from a straightforward adaptation of Christie’s novels. Virtuoso actors Eliza-Jane Scott (Lighthouse’s Jack and the Beanstalk), Andrew Scanlon (Drayton’s Peter Pan: The Panto), and Adrian Shepherd-Gawinski (Tarragon’s The Hooves Belonged to the Deer) play a total of seven roles, with quick changes and ridiculous accents galore.

“[Scanlon,] who plays the murder victim, also plays the detective,” Gallagher said. “He goes back and forth in flashbacks between the two. Adrian Shepherd-Gawinski, who’s six-foot-five, plays the Southern belle. [The costume changes] aren’t just hats. The actors leave and come on in full drag, then they leave and they come back as the next character. It’s a full quick change: costumes, wigs, everything. It’s an extra layer of fun and skill for the actors to really dig into.”

Murder mysteries aren’t a joke to Gallagher: they’re what introduced him to theatre in the first place. “I grew up in Quebec, in a small English town called North Hatley,” Gallagher shared. “It’s sort of like Muskoka in Ontario, in that a lot of wealthy people come from Montreal and go to this small town. It’s one of the only places [in Quebec] that has an English-language summer stock theatre, called the Piggery.”

Gallagher would go to the Piggery with his mother, and one of the first shows he ever saw there was a murder mystery. Murder at Ackerton Manor is “an homage to my mom,” Gallagher continued, “and those times we spent together watching — probably not great plays — but the shows that really got me into loving, and going to, the theatre.”

When he began work on Ackerton Manor, Gallagher dove back into the genre he adored as a child.

“I brought back all the [Agatha Christie] books that I had from when I was a kid,” said Gallagher. “I also watched about 50 episodes of Agatha Christie’s Poirot, and got my hands on every single murder mystery I could find, even Stephen Sondheim’s [film] The Last of Sheila that he wrote with Anthony Perkins in the ‘70s. I would get all these locked-room mysteries, [a genre in which it seems impossible for a killer to have entered and left a crime scene,] and try to figure out what I could steal. What are the tropes that are all the way through these things?

“My poor partner was like, ‘Are you up again to one o’clock watching another Miss Marple?’,” Gallagher laughed. He shared that his all-time favourite Christie novel is The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, about the mysterious death of a wealthy widower. “It sort of turns the genre on its ear,” he teased.

With its fusion of hijinks and homicide, Ackerton Manor is also a reimagining of not one, but two classic genres. Was blending farce and murder-mystery a difficult task for the playwright-director?

“[Comedy and mystery] are similar,” explained Gallagher. “Both genres need to be tightly plotted and tightly written.” He added that he’s done some tinkering with the mystery at the heart of Ackerton Manor since the play’s premiere last year at the Bancroft Village Playhouse in Bancroft, Ont. “I’ve changed a couple of things plot-wise,” he said, “just to make sure that the [murderer] isn’t something that everybody guesses; or even if they do guess it, they might not know why until the end. People love that puzzle box.”

Gallagher hopes Murder at Ackerton Manor will encourage audience members to check out Lighthouse Festival’s other offerings, and demystify how much exciting theatre is happening throughout Ontario.

“People who don’t even think they like theatre might come [see Ackerton] and say, ‘what else would I love to see?’,” he said. “Not just [a farce] but something more challenging too. We’re so used to seeing stuff in Toronto, which is amazing; but there’s a lot of other stuff happening in smaller spaces that people are flocking to.”

Murder at Ackerton Manor runs from June 12 to 29 at the Lighthouse Theatre in Port Dover, and July 3 to 14 at the Roselawn Theatre in Port Colborne. You can purchase tickets here.

Comments