Finding Home in Art

Arsinée Khanjian learns her lines through writing. By taking them off the printed page and into her own hands, the acclaimed international actor visualizes her path through a script. She prefers her paper lined and her spacing even. When we speak, she’s deep in this part of her process, rehearsing Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard (presented by Modern Times Stage Company in association with Crow’s Theatre). She’s immersed in the “collective nature of theatre,” processing how her character, Lyubov, connects to every other character in the play—even if they never share a scene.

For Khanjian, bringing a character to life is beyond playing or performing. In film, she dives deep into the world of the project, but due to the speed of the process she finds her way out much more quickly. “Theatre is altogether another experience,” says Khanjian. The transformation into a character often lingers with her after a show has closed. Hints of body language, tone of voice, even perspectives on the world echo after closing night. “That moment of realization of how different I am from my character is very pleasing,” Khanjian says. “From childhood, I always dreamt of being as many people as I could be, having as many lives as I could, being involved in as many social and political issues as I could.”

Khanjian was born in Beirut to Armenian parents. Raised in Lebanon, she holds a strong attachment to both her Armenian roots and heritage as well as the socio-political issues of the Middle East that informed her childhood and adolescence. As an outspoken activist, much of Khanjian’s work has focused on civil rights, rule of law, and democracy within the Republic of Armenia.

At age seventeen, Khanjian and her family came to Canada when the civil war began in Lebanon which continued for fifteen years. She studied in Montreal and discovered that coming to Canada offered more than practical opportunities. “It allowed me to really understand the world and the history of the world from the perspective of such a diverse society,” Khanjian says.

Coming from a culture where homosexuality was considered “unspeakable and taboo,” Khanjian says her eyes were opened to the humanity of LGBTQ issues. “These communities are absolutely persecuted, even though it is not a crime,” Khanjian says. “But it is a social reality that you can be beaten, your family can reject you, you can be literally persecuted.” Khanjian has used her platform to advocate for LGBTQ people in Armenia, regardless of the backlash she has received on social media.

As an Armenian, Khanjian shares that she holds a sense of obligation to speak about her country, the genocide, and the future of her people. However, from the moment she started speaking about LGBTQ issues on her public Facebook page, a large volume of people—who had sent her nothing but praise for her work as an artist—became very upset with her for bringing “Canadian values” into the conversation. “I constantly feel I am playing someone either on stage or social stages, understanding others and speaking in the voice of others,” Khanjian says of the connection between her activism and her art. “We can say it’s life imitating art or art imitating life, but I don’t make that distinction.”

Khanjian applies the same flexible outlook to her notions of home. When Khanjian is in Canada, she’s anxious to be in Lebanon. When she’s in Lebanon, she aches to leave for France. When she’s in France, she’s waiting to fly to Armenia. When she is in Armenia, she wants to be back in Canada. In Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, Khanjian’s character, Lyubov, returns to her childhood home carrying an immense grief over the loss of her son.

But the home Lyubov seeks is lost, and her homeland, Russia, is not as she left it. “I think I gave up on the concept of home,” Khanjian says, “because I realized that if I really look for home as a place where I’ll feel myself, […] it’s an impossible task.” She has learned, and “perhaps taught herself,” over the years to feel that home is where she is for the duration of time; to be there and to enjoy belonging to that place in a way that feels natural.

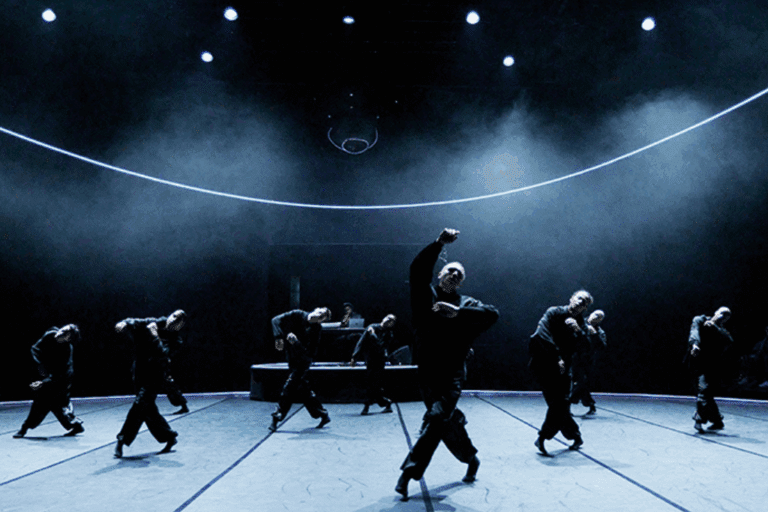

And so, for now, her current home is Toronto and The Cherry Orchard. The play connects on a core level for Khanjian and Lyubov continues to surprise and challenge her. This fresh interpretation of Chekhov’s classic, directed by Soheil Parsa, examines loss, change, transition, and rebirth. And as the landscape of the GTA continues to shift around us, and our forests and waterways are continually put at risk in favour of expanding suburbia, Khanjian says this play could not be more timely.

Comments