Wrestling with “Success”

The week of September 20, 2012, I was on the cover of NOW Magazine for their fall theatre preview. I was opening a play with Nightwood Theatre, starring in a new two-hander opposite one of my acting idols, the great Susan Coyne. I had recently closed Iceland, a sold-out SummerWorks hit that would later go on to win the playwright, Nicolas Billon, the Governor General’s Award. I also couldn’t pay my rent.

I look back on that week as a pretty perfect representation of my career and, I imagine, the careers of many others in the arts: Looks pretty good from the outside, barely keeping it together on the inside. So much of what was going on for me professionally felt exciting and inspiring, and at the exact same time I felt like a complete failure. It made me wonder—and I still wonder, all the time—how exactly am I defining success? What is it to be a successful actor?

But first, I mean… Let’s be frank. That anyone pays me to act, ever, and that I can legitimately say that it’s how I make a living (tenuous though that living may be) makes me a successful actor. I am one of the lucky ones, and I know it. But even that gives me pause. I’m a “successful working actor,” and yet I constantly live with so much uncertainty and instability, so much anxiety, so much fear and doubt. I feel like I’m pretty much a wreck all the time, and yet I’m considered a success story?

I’ve started looking at my own success—and I’m not even entirely sure how I’m defining that word—in a number of different ways. The first is the good and pure and noble one: artistic success. For a long time this was the only one that mattered to me. Am I doing work that I’m proud of? Am I challenged by it, excited by it, will I grow from it? Are the people I’m working with good people, and good artists? Is it obsessing me? If I can answer yes to these questions, even if the thing is ultimately a disaster, I feel artistically successful. Andromache kicked my ass in every possible way—physically, intellectually, emotionally—and I loved every second of it. (Audiences and critics, on the other hand, were very divided as to whether any of it worked at all.) The Road to Paradise played to small houses but was the most vitally important story I’ve ever been a part of telling. As I’ve aged, though, the importance I place on that kind of success has shifted.

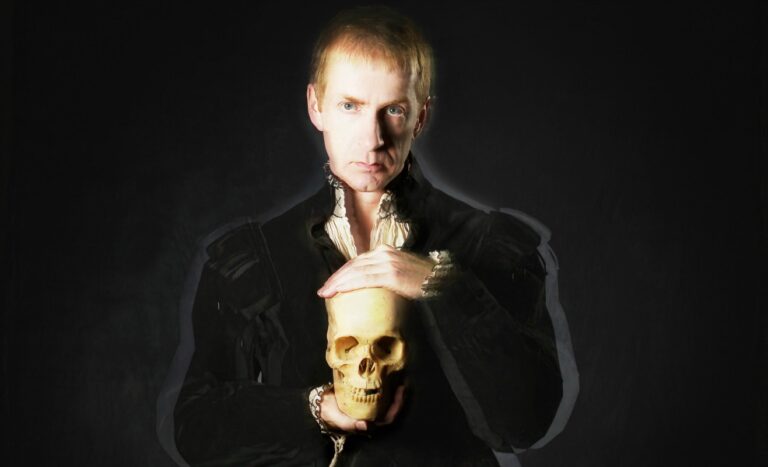

With Susan Coyne in Between the Sheets by Jordi Mand (Nightwood Theatre). Photo by John Lauener.

That week—that NOW cover/can’t-pay-my-rent week—marked a turning point. Maybe it was having turned thirty that year, maybe it was having recently moved in with my boyfriend (now my husband) and feeling like I needed to hold up my end of this partnership in a new way, but all of a sudden a different definition of success started emerging: financial. Artistic success now had a pretty fierce competitor.

Feeling like my financial stability was more important, more pressing, than my artistic satisfaction was scary. It made me feel like I wasn’t an artist. Like I couldn’t hack it, like I should go get “a real job.” And I still have those thoughts every day. When I see a “Now Hiring” sign at the bakery down the street I think, “Maybe I should just do that…”

I don’t imagine I’m an exception when I say that the financial instability that comes with this profession stresses me right the fuck out. I don’t want to have to rely on my husband to float us because I have no work on the horizon. I want to be able to take a vacation without fearing we’ll regret it, and to be able to pay off my Visa bill. I want more security, less anxiety. When I feel financially stable—and those times are scarily few and far between—that’s when I feel like I’ve got my life together. That this little career of mine is going all right; that I have made some sort of success of myself, whether I’m doing satisfying artistic work or not.

But financial stability isn’t the only measure of success that has revealed itself to be hugely important in my life. I’m also somewhat appalled to admit just how much I measure my success by what other people think of me. Whether it’s fellow artists or critics or audience members, those opinions act as a barometer of sorts. And it’s far less a question of seeking positive reinforcement than it is of needing a simple acknowledgement that I exist. Is anyone aware of my work? Am I worth talking to after a performance? Worth following on Twitter? I am high for days if someone stops me on the streetcar to say they saw The Seagull. And I don’t read reviews during the run of a show, but I sure Google them afterwards and always note if I warranted a mention, be it good, bad, or indifferent. All of these tiny ways that I feel acknowledged, that my work is acknowledged, they’re important to me. And I can’t always tell how much of that is about wanting my work to make some sort of impact and how much is just my ego. I find it embarrassing and a bit shameful, but I can’t deny that it’s part of the myriad ways I can feel like a success or a failure on any given day.

Three and a half years after that NOW cover, I find myself in virtually the same spot. Two days after a swishy gala premiere at TIFF for a film I starred in, Hyena Road, I was back to what I’d spent most of my summer doing: reading at casting sessions. At the time of writing this article, I’d just been nominated for an ACTRA Award for that same film, yet I was also pacing around my apartment in a nervous sweat praying I get an audition for something—anything—because I had no work until the spring. See? Looks good on the internet, bit of a mess in the flesh.

I always wonder how everyone else feels. When I’m envious of another actor’s career, I’d love to know how they think about it themselves. Do they feel like a fraud the way I feel like a fraud? Do they worry they don’t live up to the idea other people might have of them? We have so many tools at our disposal to present the very best version of ourselves—the smartest, the most interesting, the most attractive. It is so easy to share our accomplishments with the world. It’s so easy to spy on what everyone else is doing, and then feel woefully inadequate. Maybe I will never feel “successful.” Maybe that doesn’t even exist, and I need to find new language for whatever this pursuit is. Satisfaction, maybe. Or contentment. Though maybe if I felt those things I wouldn’t feel the need to keep going with it. Because that pursuit, that struggle, is so much a part of living life as an artist, isn’t it? If we felt we’d achieved it, we could stop. So maybe the pursuit of the thing is the thing. And maybe someday I’ll make peace with that.

Get instant loan..

$5,000 and above. at 2% rate……

Agent,,