In Conversation: Gershwyn Eustache Jnr and Leah Harvey

In April 2018, UK newspaper The Guardian began a months-long series on the unlawful detaining, deporting, and threatening of Caribbean-born British citizens by the British Home Office, and the violation of their constitutional and human rights. Named the “Windrush scandal”—after the Empire Windrush, the ship that brought the first groups of West Indian migrants to the UK in the late ‘40s, and those thereafter called the “Windrush generation”—it exposed the dangerous levels of power possessed by the Home Office, and the systemic failures of justice therein.

Now, just over a year later, and as the ripples of the Windrush scandal still reverberate through the UK and elsewhere, London’s National Theatre premieres Small Island, adapted by Helen Edmundson from British-Jamaican novelist Andrea Levy’s 2004 novel of the same name, about the journey undertaken by Jamaican British subjects, and their tumultuous welcome in the UK. With Small Island being broadcast by National Theatre Live in partnership with Cineplex Odeon on June 27, now Toronto audiences will also have a chance to catch this highly celebrated production in (movie) theatres.

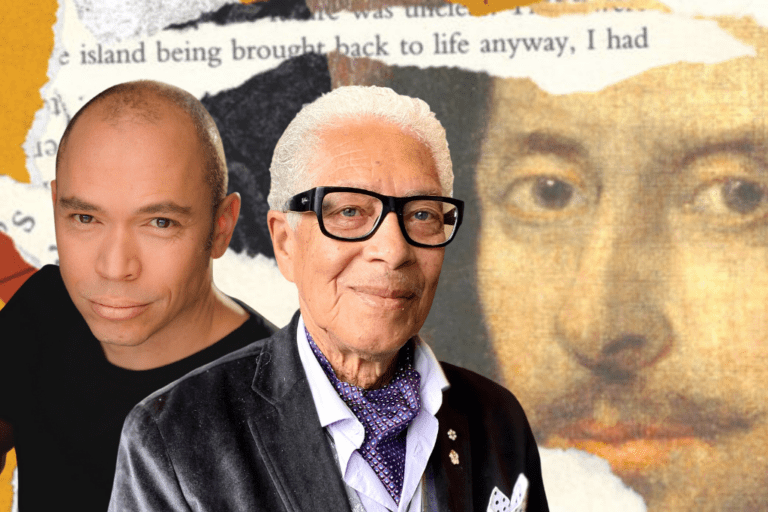

Below, Small Island principal actors Gershwyn Eustache Jnr (Gilbert) and Leah Harvey (Hortense) reflect on their characters, the legacy of the Windrush generation, and what cinema audiences can expect from Small Island.

______________________________________________________

On the most important things for a cinema audience to take away from Small Island

GE: I hope they enjoy the show and laugh but I also hope they take away how tough things were back then for that generation. Also, an open-mindedness. People aren’t always looking to “take what’s yours.” The characters in the show just want the opportunity to make the best for themselves and their own.

LH: This is an epic tale told on a big stage by over 40 actors. Naturally, you can miss the little details if you’re sitting in the audience in the theatre. But, being able to see it from this point of view will give us a chance to see the nuances of the characters and little gems of storytelling. Hopefully the audience will feel more connected to those sitting next to them by the end!

Gershwyn Eustache Jnr and David Fielder in Small Island. Photo by Brinkhoff Moegenburg.

On the difference between acting for the stage and acting for “the-stage-that-is-being-filmed”

LH: We don’t change anything about our performance. It’s about giving the audience as close an experience of what it’s like to be in theatre as possible. There may be some changes for things like make-up—for example I have quite rosy cheeks in the theatre so the people far away can see my expressions, but we’ve toned that down a bit for the cameras because it just wouldn’t look right. But other than that, what you see in the cinema is what the audience in the auditorium that night is seeing.

GE: During the first camera rehearsal I was a little conscious about looking/not looking at the camera while directly addressing the audience, but you realise the NT Live team really do the work for us and we don’t have to change anything we do from night to night when the cameras aren’t in. There’s a lot of preparation that goes on in the run up to a broadcast. The camera director and the crew watch the show in the theatre and via a recording so they can plan their angles. Then we have two camera rehearsals, and there’ll also be a playback after the first so they can tweak anything they need to.

Leah Harvey in Small Island. Photo by Brinkhoff Moegenburg.

On what the UK represents for Hortense and Gilbert, and how that changes throughout the play

LH: For Hortense, the UK represents a better life. Her mother gave her away when she was young to try and give her that, so that’s instilled in her from a young age. She has an idealistic view of London, that she’ll move there and her life will be great, and she’ll be a teacher like she was in Jamaica—but of course, it’s not that simple. She’s not treated the same way she was in Jamaica and she has to struggle with the idea that it might not be the life she dreamed of.

GE: For Gilbert (like Hortense) the UK represents a better life, as it did for most people who came over on the Windrush. The difference between Gilbert and Hortense’s view of the UK is that he had been there before they move to London because of his RAF (Royal Air Force) service. He knows what to expect – he’s seen the bad weather, pretty terrible living conditions, and the racism. But he still sees the UK as somewhere he can make a better life than he could back home, so he keeps going. He’s an optimist for sure but you see later in the story how it starts to wear him down. Every human, even if it’s more than most others, has a limit of how long they can keep battling adversities, and we see Gilbert reach his limit.

Cavan Clarke, Adam Ewan, Paul Bentall and Gershwyn Eustache Jnr in Small Island. Photo by Brinkhoff Moegenburg.

On how the legacy of the injustices carried out against the Windrush generation and their descendants affected the creation and rehearsal process

GE: For me playing Gilbert, I wanted to make sure he wasn’t a caricature. He’s my dad, uncle, neighbour, etc. I wanted to do him—and the people he represents—justice and show what actually happened as honestly as possible. We had a visitor during rehearsals called Alford Gardner who was a passenger on the Windrush who is now 93 and he really inspired us all. He is Gilbert. His life, energy, spirit, and his dignity showed me even more what my character was about. They made very brave decisions to leave home.

LH: A lot of us in the cast have family members who were alive during the Windrush era, so it was always present, and we wanted to make sure we represented them well. We did a lot of research, including visits to the Black Cultural Archive to look at photos and other artefacts. We also had a picture of (Small Island author) Andrea Levy and her mother on the wall of the rehearsal room, and which is now by the stage, so they’ve been with us the whole time in spirit.

Leah Harvey in Small Island. Photo by Brinkhoff Moegenburg.

On what Small Island can say from the stage and screen in this current moment of escalating xenophobia and anti-immigration sentiment

LH: In London theatres at the moment, we’re seeing stories on the stages with people and by people who have never had that platform before. The fact that London theatre is so successful right now (last year was a record year for box offices) shows that the interest is there for those stories and that they can be successful. There’s a real energy in the room every night, which just shows how relevant it is. I certainly feel like we need to hold on to each other in this current political and social climate. Hopefully this play helps us see the things we have in common rather than how we are different!

GE: I think it’s important that this story is getting a moment, and that moment is happening in one of the UK’s biggest theatres. It shouldn’t ever be forgotten what this generation of people contributed to this country, and how badly they’ve been treated since. The show sold out here at the National Theatre not long after press night, which shows people want to see these types of stories and they have a rightful place amongst any other play or production.

Gershwyn Eustache Jnr and Leah Harvey in Small Island. Photo by Brinkhoff Moegenburg.

On why it’s important for audiences in Canada to see Small Island

GE: You don’t have to be British or Jamaican to take something from it. It’s an important piece of work, it doesn’t hold back, and though it’s a tough watch in parts, you’ll also laugh. The response from the audiences has shown us that you don’t know what will trigger a particular emotion in someone watching this show, which is a real testament to the work. I also have family in Canada so means a lot to me that they will be able to see it.

LH: I think it’s important for anyone and everyone to see it. I think everyone can find something in it, even if it’s just one second. There’s something that applies to everyone in this show.

Comments