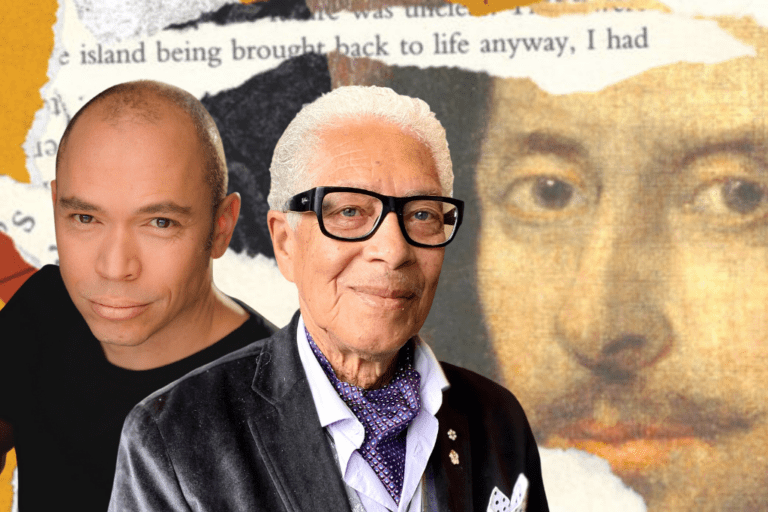

Making Theatrical Ghee: In Conversation with Philip Akin and Aldrin Bundoc

When Philip Akin agreed to direct Maanomaa, My Brother, the poignant, riveting new play by Tawiah M’Carthy and Brad Cook at Canadian Stage, he didn’t read the script first.

“I didn’t have to,” he said over Zoom. “Tawiah called me up, and he said, ‘hey, I’m doing this thing, and I’ve written it with Brad and I want you to direct it.’ I asked about dates, and that was that. I said yes because he asked me – the thing that drew me to this project was specifically Tawiah.”

That may seem like a surprising answer to the question, “why did you want to direct the world premiere of this play?,” but in truth, Maanomaa is a surprising project. Weaving together Twi and English languages, and cultivating an aesthetic style somewhere between dance and physical theatre, the play is both fiercely personal and curiously abstract, a meditation on grief and diaspora between two childhood friends, played by M’Carthy and Cook.

Maanomaa, My Brother takes place in Ghana, meaning the creative team had to carefully consider a range of stylistic choices, from costuming to dialects to music. How should Cook, who is white, portray Black characters (the play is a two-hander with a multitude of characters), for instance? And how could aesthetic details be used to suggest childhood versions of the men onstage? By the time Akin had stepped on as director, much of Maanomaa, My Brother was already set in place. But joining the team late was a rewarding part of the challenge, he said.

“A huge amount of work had already gone into [the production], and there were concepts in place,” he told me. ”My job was to clarify things. To make things clearer. To look at what was accepted knowledge and practice within the rehearsal hall, and challenge that. Because, frankly, a lot of times, especially with a process that’s gone on this long, there’s just things that become accepted. And it’s my job to ask, ‘why?’.”

One instance of this sort of “editing,” said Akin, was pre-recorded speech, which M’Carthy and Cook intended to pipe into the theatre in darkness during the show. Akin had other ideas.

“That’s stupid,” he said, laughing. “Why are we doing that? And they said, ‘well, we’re doing that because we want to do that.’ And I said, ‘okay, fine, but who wants to sit in a room of live theatre and listen to someone talk over the speaker in the dark?’ That’s not theatrical. That’s not engaging.

“I came to Maanomaa to challenge precepts, not to get my own way all the time, because that’s not the point. The point is to have these conversations, to bring a fresh eye, and to be very, very clear, down to the word, about what’s being said, and if what’s being said is what’s meant to be said. This wasn’t about building a big, philosophical overview. It was about putting a magnifying glass on what the story was.”

Akin has a metaphor he uses for that clarifying process.

“I eat butter,” he said. “But if you go to Little India, you can buy a jar of ghee. And what’s that? It’s clarified butter. It’s butter with all the solids taken out of it that could go bad. So ghee can stay on your shelf for months and months. So I think of myself in this process as the guy making theatrical ghee.”

Akin is not, in his words, “a big believer in sitting around the table,” so when he starts a rehearsal process, it’s standing up, playing, searching for kernels of truth in the body as well as the mind. That’s where the “ghee” comes in.

The prolific director didn’t work alone on this clarifying process – he had an assistant director, Aldrin Bundoc.

“I bully him mercilessly,” said Akin. “And it’s been great. We’re at different stages of creating our directing processes, which means cultivating our own artistic voices, how we approach things, how we see the world.”

“It’s been a really fun process,” said Bundoc. “Philip has this way of creating a lot of levity in the room. He doesn’t bully me,” he added, laughing. Bundoc first joined Maanomaa, My Brother as an assistant movement director – a huge job, given the physical demands of the play.

“I came into this wanting to strengthen my voice as a creative, from an angle that isn’t as an actor. I’m an actor, and that’s always been my access point to creating. But to be a fly on the wall, sitting behind Philip and seeing what he’s doing, is really cool.

“What’s beautiful about this piece is that there’s so much story that isn’t told through words, it’s told through movement,” continued Bundoc. “Yes, there was a lot of dramaturgy work to make things fit. But it feels like that process has been effortless on Philip’s end. And that’s really, really wonderful to watch.”

“We’re just trying to tell a story,” said Akin. “And that’s really, really simple. It’s a human story. If I can keep coming at it from the point of view of these human beings telling a story touching other humans, then I don’t actually have to worry about everything else.”

Maanomaa, My Brother ran at Canadian Stage April 11–30, 2023.

Comments