REVIEW: Talk is Free Theatre’s Blackbird offers a close-up look at two detailed performances

Among traversing the globe, producing Sondheim musicals, and conducting site-specific experiments in its hometown of Barrie, Ontario, Talk is Free Theatre (TIFT) has taken to putting on well-acted stagings of contemporary Anglophone scripts just old enough to have been forgotten.

Nine months ago was Mike Bartlett’s Cock, an English play from 2009, at a circus studio in Toronto’s east end; and now there’s David Harrower’s Blackbird, a Scottish drama from four years earlier, in an office at Hope United Church on the same side of the city. Emerging director Dean Deffett has concocted a tight, straightforward production, primarily of interest as an intimate character study.

In one location, a long-awaited encounter leads to a spiral of reveals about the past: Yes, Blackbird’s structure is fairly conventional. But its content glows with danger. Ray (TIFT regular Cyrus Lane), a 55-year-old white-collar worker, finds a 27-year-old woman named Una (Kirstyn Russelle) at his office. He doesn’t recognize her at first, because their last meeting happened when she was 12, and he was her sexual abuser — a crime for which he spent three-and-a-half years in prison.

Ray has meticulously refashioned his life. He’s taken on a new identity in a new town, and even has a wife. There’s an unreal quality to Ray and Una’s meeting; Harrower implies that both previously assumed they’d never see each other again. While Una doesn’t articulate a precise reason for tracking Ray down, it appears to me that her motivation partly stems from the need to reaffirm the past — to confirm that her trauma is real, and that there’s another person out there who remembers the events with similar vividity.

Her desire to retrace history gives way to dialogue that painstakingly maps the duo’s affair. On the level of design, Deffett doesn’t do much to add theatricality to these lengthy stretches of exposition. The only lighting source is the room’s harsh, built-in overhead (no designer credited). And the church’s tiny, cage-like office feels entirely realistic, with the floor’s discarded Tim Horton cups signalling a Canadian setting (set and prop coordination by Lauren Cully).

The space’s tightness means the actors’ reactions are highly visible, and it’s fascinating to track their characters’ intense reactions.

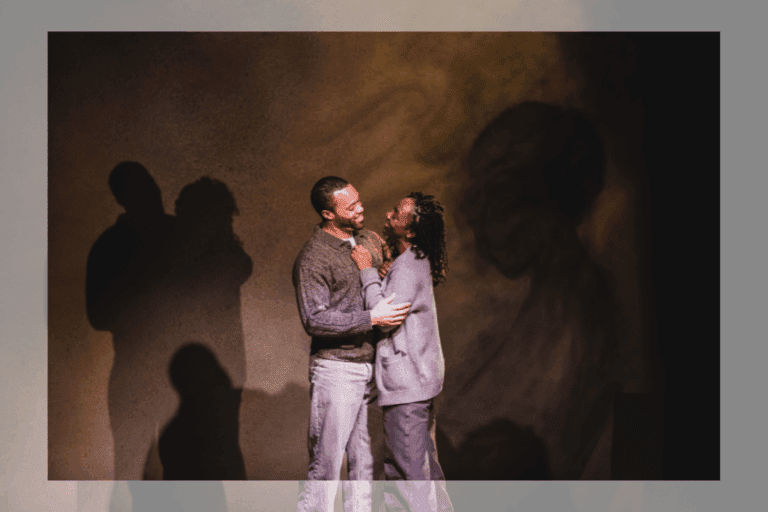

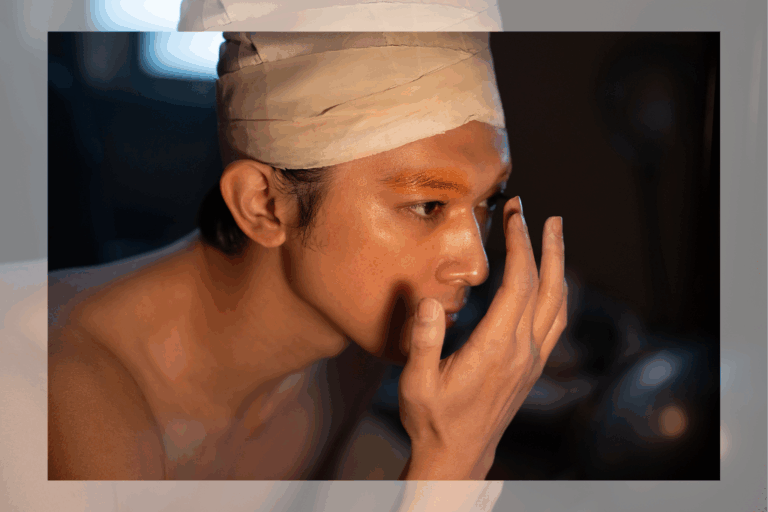

Una’s presence crumples Ray. After recognizing her, he takes on an immense physical heaviness. His eyesight drifts toward the floor, his body rigid with stress. A centre-stage table supports his attempts to keep himself upright. Speaking also requires labour: text lurches out of him uncomfortably, an extension of his pained exhales. Lane’s brutal, boxy physicality, clothed in neutral office wear (designed by Sequoia Erickson), exudes a dissociative aura; his character is so overwhelmed that he can only afford the occasional, desperate movement. His mental fog clouds the office.

But Una evinces mercuriality. While Ray’s energy tends to slant forward, she defaults upright, often backing herself up against a bookshelf or wall, grounding herself in defensive but powerful positions. Her hands flit about, nervously searching for an activity other than nail-picking. Russelle’s physical agitation mirrors the turbulence of Una’s mental state. More than once, she springs forward with a confession that would seem to change the terms of the encounter; her words hang in the air for a moment before she changes courses, taking a step back. During these outbursts, her emotion manifests in a tense, quivering neck.

The production’s excitement lies in observing these behavioural patterns. Even when the text gets stuck in a web of description, the actors’ subtle dynamic churns on. Through their carefully sculpted performances, the show’s topic becomes power. Una could raze Ray’s new life, but she abstains from verbal threats. Her agency instead manifests in physical and emotional changeability. While Ray stands paralyzed, Una tests different ways of occupying the space — different routes the encounter could go. Fifteen years ago, he was in control; now, she’s the one following her impulses.

Blackbird runs at Toronto’s Hope United Church until October 18. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments