REVIEW: Frozen River at YPT/Manitoba Theatre for Young People

Frozen River (nîkwatin sîpiy), the new play from Manitoba Theatre for Young People at Young People’s Theatre, emphasizes the importance of keeping promises, even if it takes seven generations to do so. The hour-long show, co-written by Michaela Washburn, Joelle Peters, and Carrie Costello and directed by Katie German, uses the story of two unlikely friends from different worlds and their descendants as an elegant metaphor for the impact of colonialism and the potential for reconciliation.

Two children are born under a blood moon, but neither cries, even though our narrator Grandmother Moon (Julia Davis) is quick to assure us that nothing is wrong with the act of crying. In this case, however, “one was busy doing, and one was busy seeing,” so there is no time to cry. One child grows up in Scotland and the other in what is now called Manitoba, but Elidih (Emily Meadows)’s family immigrates to the province after their farm is burned to make way for sheep pasture. They build a sod house and settle into the frozen landscape, depicted as refugees who have lost everything and moved for a second chance at life.

Though Elidih’s family is being forced to start over, they are still making incursions into land that is not theirs. This is emphasized when the 11-year-old Elidih meets her birthday twin Wâpam (Keeley McPeek) on a trip through the wilderness while her mother gives birth to her younger sister. Wâpam is initially cautious, with only a twig snap alerting Elidih to her presence. However, the two soon warm to each other, trading information about themselves and what is safe to eat in the forest with a series of exaggerated gestures.

As the two learn each other’s languages (Wâpam more ably than Elidih) and slowly become part of each other’s families, Elidih offers an exchange: Wâpam can stay with her family one winter, and Elidih will come with Wâpam’s family on their winterly migration the next year. They’ll learn each other’s cultures and skills. It soon becomes clear, however, that Elidih is only interested in one half of the exchange, wishing her friend’s values could become more like hers.

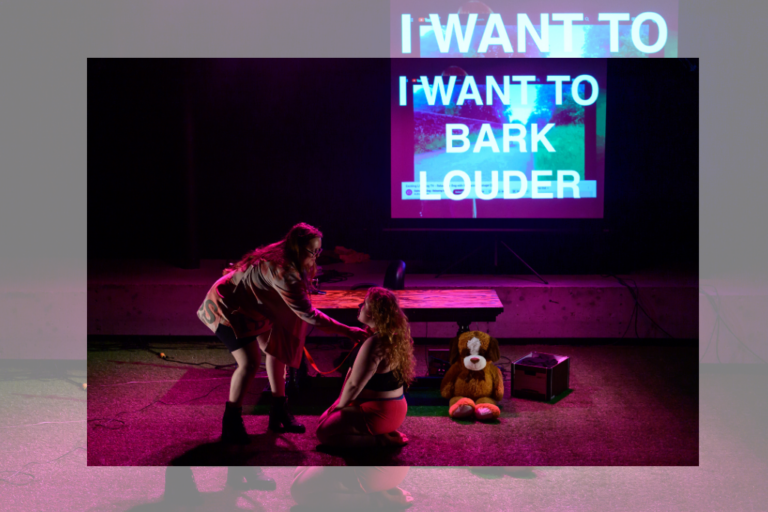

Under German’s direction, Frozen River keeps things visually interesting by using shadow puppetry, creating projections of animals and landscapes on a large circular set piece that resembles a giant drum and occasionally turns into a moon (by set and props designer Julie Lumsden). This imagery is a lot of fun, and could be even more prominent throughout the production. There are physical puppets as well, a realistic but slightly stiff marionette child manipulated by Davis to represent Elidih’s infant-to-toddler sister, and a delightful, more fluidly-moving turtle puppet in the second half.

McPeek and Meadows create a believable relationship with enjoyable chemistry, both young women showing grit and determination to make lives for themselves. They share sweet moments at the beginning which show the excitement of cultural exchange and learning. Later, more shading might be possible in the devolution and conflict in the relationship, where Elidih’s rejection of everything Wâpam values, especially the chance that Wâpam will pass on this knowledge to the next generation via Elidih’s sister, leads to a massive rift.

Even though the show is for young audiences (recommended for ages 5-12) and effectively delivers a direct moral, I felt more could be made of exploring the roots of Elidih’s prejudice so that the lessons might carry over further into interrogating one’s own xenophobic impulses, should they arise. If Eilidh’s fear of a second loss of her own way of life were made clearer, for example, her actions might seem more organic. This might also allow Wâpam to be an even more well-rounded character herself in her impassioned reaction to Elidih’s betrayal.

Toronto is covered by the Dish With One Spoon treaty, which means that we all share the same resources, and it’s our responsibility to make sure that we don’t take more than can be replenished. In a Toronto venue where this treaty is acknowledged, it stands out that the first interaction between Wâpam and Elidih is a breaking of that promise. Seeing her flask is empty, Wâpam offers Elidih a drink of water; after hesitantly accepting, Elidih takes a short drink, then proceeds to drain the container dry.

This metaphor is made text in the second part of the show via a look into the water crisis on the reservation where Wâpam’s descendant lives, a situation she archly describes to Elidih’s descendant in the school library as “complicated.” The two young women, also birthday twins, make each other’s acquaintance once more in a present where the word “reconciliation” is often tossed around, but rarely understood. Both Meadows and McPeek (doubling in these roles) shine in this section, which emphasizes the importance of listening to others over talking while giving us several excellent zingers to listen to.

Though the production could do with a little extra amplification in the presence of an excitable elementary-school-aged audience, its message is loud and clear. We can’t change the past, but our responsibility to the next seven generations begins today.

Frozen River closed at YPT on April 28. Learn more about the show here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments