REVIEW: Hamlet at Stratford Festival

Engaging, energetic, and efficient.

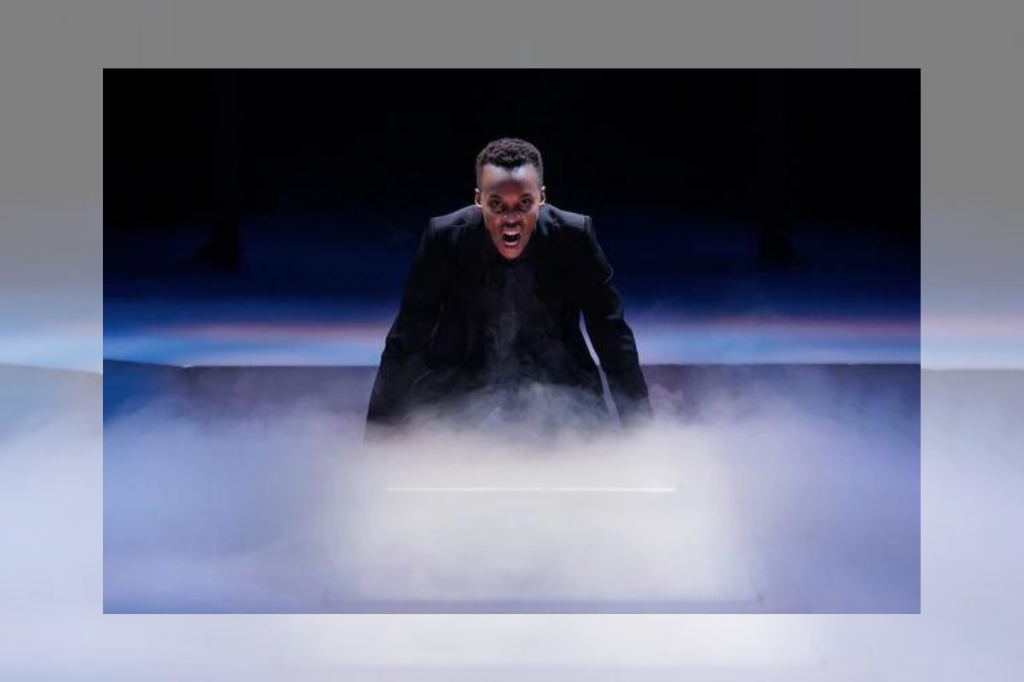

The three words that come to mind as I leave the Stratford Festival’s latest production of Hamlet. Starring Amaka Umeh as the titular troubled Prince of Denmark, director Peter Pasyk’s modernized production of Shakespeare’s tragedy is a bold and exciting presentation of the classic tale.

Despite a solid ensemble and striking design, it’s Umeh who carries this show. She presents the role with a level of naturalism, charisma, and a sense of play I often find lacking in modern Shakespeare. It’s clear that Umeh is an athletic performer — her turn as the silent but highly physical #00 in Howland Company’s 2017 production of The Wolves earned her a Dora Award — and it’s her ease and comfort on stage that truly brings her character to life.

Although Umeh is the first actor of colour and first woman to tackle the coveted role of Hamlet in the Stratford Festival’s 70-season history, her Hamlet uses he/him pronouns throughout the show.

It seems as though Stratford is commenting on restrictive casting policies, making the statement that anyone can take on the role of the grieving prince, and Umeh certainly proves them right. But some moments within the show make the production’s gender-blindness seem like a missed opportunity: in Act I, scene ii, King Claudius (a surprisingly empathetic and sensitive portrayal by Graham Abbey, a Stratford regular) rebukes his stepson for wallowing at his mother Gertrude’s wedding (played by another of the festival’s familiar faces, Maev Beaty) with the line, “‘tis unmanly grief.” Upon hearing the word “unmanly,” Umeh, in all her reactive brilliance, gave a small, bitter smirk: a subtle choice that I was excited for the production to build upon.

This simple moment immediately made me wonder how gender might play into this plot. Is Hamlet a woman whose family refuses to see her as such because of her place in line for the throne? Or is the prince’s gender a symbol to be revealed later in the show? Countless possibilities, but the small moment ultimately went unexplored. While Umeh’s deeply truthful performance was able to capture all the nuance and erratic energy of Hamlet’s grief, unarguably demonstrating that gender and race are in no way a barrier to exploring Hamlet’s character, it felt as though the creative team could have been more imaginative in their approach to what is, ultimately, a highly gendered play.

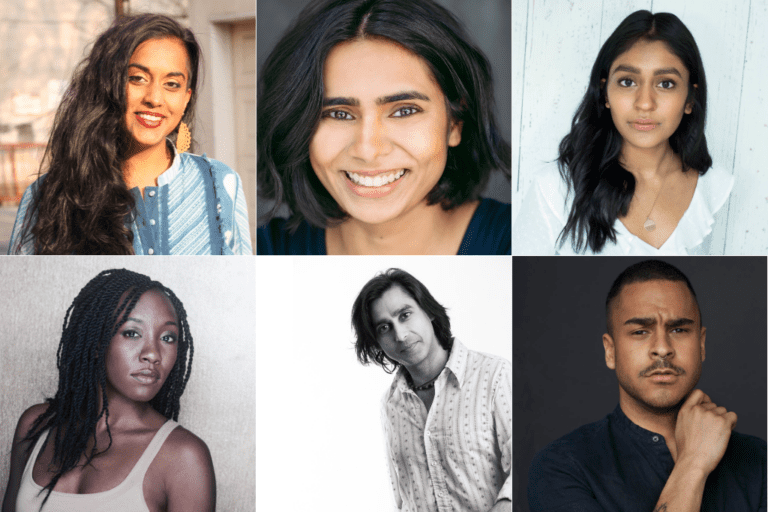

Indeed, the characters in Shakespeare’s original text make several comments on gender throughout the show — Hamlet himself blames women for his predicament, railing against both Ophelia (Andrea Rankin) and Gertrude in multiple points of the play. Placing more of a focus on the decision to cast a woman as Hamlet certainly wouldn’t have seemed out of place in a production that has already made the bold choice to heavily incorporate technology into its plot and presentation.

Pasyk’s Hamlet successfully emphasizes the generational differences between characters in the production, with younger characters relying heavily on cellphones to build out scenes. There are selfies, love letters in the form of text messages, and what one can only presume is a suggestive image sent from a certain young prince to Ophelia. During the famous play-within-a-play of Act III, scene ii, Horatio (Jakob Ehman) films Claudis’ reaction, again speaking to the timeliness of the show. The cellphones never seem out of place, and are used just enough to remain an effective choice without distracting from the plot.

The production’s design again places the focus on the differences between the old royalty and the new. Michelle Bohn’s costumes reflect the very real conversations of the relevance of monarchy in a modern world, with the older characters wearing crisp, pressed suits and elegant gowns in muted tones, while the younger players wear brighter colours, wilder patterns, and clothing set distinctly in 2022 (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern enter in a cloud of vape smoke and flashy pants — it’s like waking through Toronto’s Trinity Bellwoods on a Tuesday evening).

Similarly, set designer Patrick Lavendar has created a space that screams of juxtaposition — the lower tier of the two-storey set resembles a classical house with wood finishes and subtle yet elegant furniture, while the upper level is modelled as a high-security facility, complete with glass panels and a walkway that provides a strategic view of the entire set. (The implication that the characters are being surveilled did leave me wondering how nobody on the watchtower witnessed Claudius murdering his brother, given the apparent view of the entire premises, but I digress). Indeed, there is an overwhelming sense of pretense throughout the show — from the opening scene, the characters feel trapped, constantly under surveillance in their palace amongst their riches.

Kimberly Purtell’s clever lighting design illuminates the area behind the glass, creating a contained and focus-pulling space in which the actors can play in an otherwise dark stage. The production uses silent vignettes to explain some of what occurs offstage between scenes, but some of the vignettes seem to confuse otherwise straightforward moments. For example, a mimed segment showing Hamlet physically restraining Ophelia is meant to clarify the next scene, Act II scene i, in which Ophelia discusses Hamlet’s erratic behaviour with her father (“He took me by the wrist and held me hard; Then goes he to the length of all his arm; And, with his other hand thus o’er his brow, He falls to such perusal of my face.”). From where I was sitting in the centre audience bank, Hamlet appeared to seize Ophelia by the neck, creating a scene much more violent than what she describes just moments later.

Stratford’s Hamlet is at its best when the actors leave the stage and make use of the audience, making the crowd a part of the action both as spectators and, ultimately, accomplices. Suited security guards are present throughout the bulk of the show, patrolling the walkway above the stage, standing in the aisles, and even popping out through a small porthole high above the set. During the fated performance of “the mousetrap,” the royal family enters through the aisles, joining the audience in a beautifully simple but visually stunning sequence that draws the audience directly into the plot. While it was difficult to see Claudius’ reactions to the story until his abrupt departure (in which the lights snapped on throughout the entire theatre house,” Umeh remained mobile, standing, pacing, and allowing the audience to see Hamlet’s reactions without distracting from the plot.

For a three-hour show, Stratford’s Hamlet zips right along, with energetic performances from everyone involved, helping to keep the audience invested and interested in the piece while avoiding the dreaded “Shakespeare voice” that so so often permeates North American theatre. That said, there’s some gratuitous midline pausing throughout the entire cast, without which the show might have saved a solid fifteen minutes. The exceptions are Laertes and the ghost of Hamlet’s father, played by Austin Eckert and Matthew Kwabe respectively. These two actors stand out in all the right ways with a seamless, naturalistic handle of difficult language, metre, and rhythm.

Despite my incredibly small criticisms, I must admit that this production is one of the better presentations of Hamlet I’ve seen in my life (and I’ve seen Hamlet a LOT). It’s fun (even though it’s a tragedy), easy to follow, and overall, the performances keep the production alive and energetic without sacrificing truth and objective for speed and volume. Umeh’s performance places her among the ranks of past Stratford Hamlets, including Colm Feore (onstage in this season’s Richard III and The Miser) and the late great Christopher Plummer and Brent Carver. Umeh’s success in the role has made one thing clear: when it comes to casting classical theatre on Canadian stages, there are simply no more excuses for all-white casts and creative teams.

While Umeh’s performance as Hamlet speaks for itself outside the history it makes for casting practices at Stratford, and the Festival should not simply be lauded for her casting. Rather, we must recognise that Umeh’s brilliance on-stage is the product of her own hard work, immense talent, and a clear desire for greatness. While it’s unfortunate that it’s taken until 2022 for more diverse casting in classical theatre to find its way onto Canadian stages, her success in the role has made one thing clear: there are no more excuses.

Hamlet runs through October 28 at Stratford’s Festival Theatre. Tickets are available here.

Comments