REVIEW: The House of Bernarda Alba at Aluna Theatre/Modern Times Stage Company/Buddies in Bad Times Theatre

Content warning: this review contains mention of suicide.

“There’s nothing worse than being born a woman. Even our eyes aren’t our own.”

Indeed, in The House of Bernarda Alba, being born a woman is considered the ultimate crime; repressed and restricted to the house, the women of the 90-minute play boil with intensity as a family, wracked with turmoil and threatening to implode.

Upon the death of her second husband, domineering matriarch Bernarda Alba imposes a strict eight-year period of mourning on her five daughters, effectively placing them in an extended lockdown inside their home. Despite the omnipotence of a tyrannical mother, the girls each rebel in their own small way, desperate to reach the world beyond and escape the constraints of a shared family obligation.

Modern Times Stage Company and Aluna Theatre’s adaptation of Federico García Lorca’s final play drives its message home with an unyielding hammer. Written in 1936, mere months before his assassination, the famed Spanish playwright’s uncompromising script paints a harrowing portrait of a family at its breaking point, trapped in a battle between oppressive tradition and youthful freedom. It’s a story of women on the verge of breakdown, trapped by circumstances they did not choose and rendered powerless because of their gender and station. The ninety-minute co-production is succinct and at times spell-binding, although it occasionally falls victim to its own intensity, sacrificing nuance for tension.

At first glance, the stage of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre (where the production’s taking place) gives nothing away: stark white curtains with harsh black lines frame the stage and jagged white forms litter the floor, in contrast with the antique wooden chair that sits directly centre stage. As the show begins, it quickly becomes clear that the design is deliberately barren, reflecting the contrasting desires of mother and daughters in a clash of wills. The intimate space serves the show well; Buddies’ raked seating ensures that audiences will have a clear view of the action regardless of their seating, and Soheil Parsa’s simple yet clever direction creates clear sightlines without sacrificing the plot. It truly feels like the home is splintering, reflecting the broken women it houses.

While conflict is the main focus of the show, there are moments in which the play feels stylistically disjointed, toeing the line between naturalism and heightened drama. Beatriz Pizano shines as the play’s titular matriarch, delivering a transformative performance that is equal parts terrifying and heartbreaking. Though Bernarda is often ruthless and unflinching, Pizano makes the most of her moments of vulnerability, which are amplified by the echoing cries of Maria Josef, Bernarda’s mother, who’s kept locked away in a back room. In one particularly powerful moment at what would typically be the end of act one (this production’s a truncated one with no interval), Bernarda is almost frantic, whispering to herself with tears in her eyes as her mother’s trembling cries reverberate through the space. This is my first experience of Pizano’s work, and I can easily see why she is such a celebrated actor.

But the true star of the show is Rhoma Spencer, who delivers a delightfully rich portrayal of Poncia, a servant and close confidant in the Alba home. As the only close member of the household who is an outsider to the family, Poncia speaks her mind loudly and often, and Spencer masterfully navigates her moments of power without letting us forget her place. The show starts with an extended moment of exposition between Poncia and a maid, played by a thoroughly committed and appropriately comical Soo Garay. In clumsier hands, that scene might have felt forced, but Spencer’s charismatic storytelling and specific choices make a scene prone to melodrama feel completely natural. Indeed, there were moments in which I found myself wondering if Spencer was even acting; the naturalism with which she presents Poncia is beautiful to behold, and she easily diffuses and creates tension in all of her scenes.

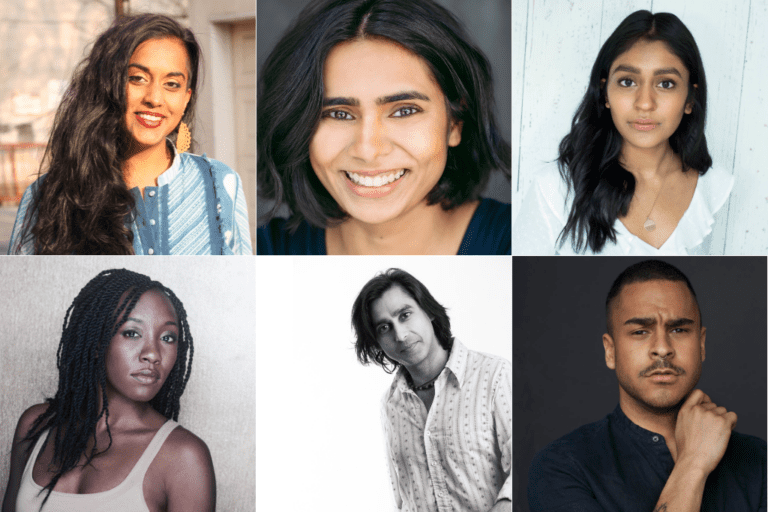

Bernarda’s five daughters, played by Lara Arabian, Monica Rodriguez Knox, Theresa Cutknife, Liz Der, and Nyiri Karakas, provide another layer of contrast, this time in their approach to their respective characters. Where Bernarda and Poncia are complicated and frenetic, each of the younger women feels firmly planted in one emotion; for most of the play, they display an understandable anger, but it often leaves them with nowhere to go. One particularly explosive scene between the two youngest Alba daughters, Adela (Karakas) and Martirio (Der), starts so high that the news of a young village woman being tortured for the birth and murder of her illegitimate child falls flat — it’s an underwhelming revelation compared to the argument we’ve just witnessed.

That’s not to say that the show is one-note — a beautiful moment in which Poncia sings to the girls provides a moment of peace in an otherwise combative story — but the anger that radiates through the household is at times overwhelming, leaving little room for the sexual tension inherent in the script. García Lorca deliberately places the men offstage, unseen and mostly unheard, to fuel the sexual tension that lives within each of the unmarried, supposedly virginal daughters of the Alba family, but that tension is pushed aside for a more aggressive type of conflict. When Bernarda’s daughters rush to watch the men from the porch or their windows, it reads as curiosity or a means of escape from their mother, rather than desperation and animalistic desire.

The sole moment in which we hear the men’s voices provides a much-needed moment of release for the women; a sonorous chant fills the space as male harvesters head to the field, unseen but fully heard. Bernarda’s daughters close their eyes and gyrate gently to the music, bodies moving almost unconsciously in time with the beat. The tension is almost orgasmic, portrayed in the most fleeting of moments, equal parts beautiful and haunting, the only time in which the girls’ sexual frustration shines through a rigid exterior.

The play’s three act structure has been condensed into a succinct ninety minutes, a welcome choice that moves the plot along nicely. While several scenes featuring nameless villagers have been removed or reduced, I didn’t find myself missing them; however, the choice to have Maria Josef offstage for most of the show leaves me with questions. While Maria Josef is not a pivotal role in the story, in this production she is merely a terrified voice echoing through the space, and in one moment with Martirio, a ghostly figure crossing slowly behind a sheer curtain. There are points in which she seems only to exist in Bernarda’s mind, an illusion that is broken when other characters acknowledge the elderly woman locked in a back room — it feels like a missed opportunity for a stronger choice.

Parsa understands how to let the text live at the forefront of storytelling; there are few bells and whistles in this production, with focus firmly placed on the fractured relationships of the Alba family. His direction creates some truly lovely moments, particularly between Bernarda and Poncia, and the daughters move deftly but carefully through the space, a choice that only reinforces the feeling that they are trapped in someone else’s home. The only moment I truly question is (spoiler ahead) Adela’s death, which is accompanied by the sound of glass breaking. It’s an unclear moment that slows down the end of the play; even when Poncia reveals that Adela has died by suicide, it isn’t clear what happened, and the moment is further confused when Bernarda instructs the maid to cut her hanging body down. The usually powerful ending of the show, in which Bernarda firmly declares that her daughter died a virgin, and thus cementing her obsession with appearances and reputation, doesn’t have its usual impact here, and on opening night it was truly unclear if the show was over.

The House of Bernarda Alba succeeds in transporting its audience to the past while keeping the story firmly rooted in the present; indeed, after almost two years of isolation and lockdowns, it’s easy to relate to the stress of being trapped (a recurring theme in Toronto theatre post-pandemic, it seems). For a show focused on conflict and pain, the mood was surprisingly light as the audience left the space; the stronger moments of the production overshadow its weaknesses, and several powerful performances leave a lasting impression which transcends realities of isolation and loneliness.

The House of Bernarda Alba, an Aluna Theatre and Modern Times Stage Company co-production, runs at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre until April 24. You can find tickets here.

Comments