REVIEW: Three Sisters at The Howland Company/Hart House Theatre

“Three years ago, I was so happy.”

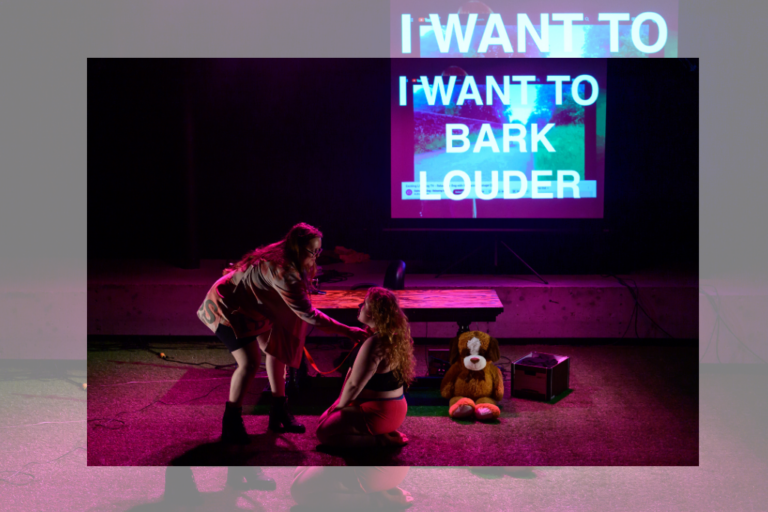

When youngest sister Irina (Shauna Thompson) in The Howland Company and Hart House Theatre’s co-production of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters wistfully sighs this line, or when her siblings speak of the trapped feeling caused by constant stasis and interminable boredom, it’s hard not to think about the upheaval of the last three years of our own lives. Director and adapter Paolo Santalucia offers a largely faithful, slightly modernized adaptation of Chekhov’s ode to yearning and ennui, with a contemporary set and costumes (both by Nancy Anne Perrin), and occasional references suggesting the play takes place in the here and now. The show shines in its passionate performances and moving, melancholic speeches. However, much like its characters, the production’s attempts to make changes don’t really give it the purpose it seeks.

The titular sisters lament their lives since moving to a small town from the big city more than a decade ago. Now that their beloved father has died, there is little tying them to the place they were transferred for his military career. However much they long to leave their house to go back, though, they seem unable to make the first move.

Eldest sister Olga (Hallie Seline) works long hours at the local school; middle sister Masha (Caroline Toal) struggles with depression and disdain for her well-meaning but terminally goofy and endlessly talkative husband Theo (Dan Mousseau, filling in for Colin A. Doyle on November 2), and youngest sister Irina enchants everyone around her but can’t feel the same love back. Meanwhile, their brother Andrei (Ben Yoganathan), who dreamed of becoming a professor, instead languishes as an assistant clerk, falling into gambling and proposing to his universally-disliked girlfriend Natasha (Ruth Goodwin) for something to do. The house becomes a gathering place for bored soldiers, feuding suitors, and family friends as time drags on and frustrations grow.

Santalucia’s adaptation is most effective when it focuses on character, highlighting themes that remain timeless and universal. The current generation is caught between accusations of apathetic laziness and the reality of long, exhausting workdays; Andrei’s whine that he is anxious both when he is working and when doing nothing might as well be tagged #relatable. Characters dream alternately of an apocalyptic or positive future, hoping that their children create a better world, but fearing their anger that their parents did nothing to change it.

Both Irina and sentimental, drunk family friend Ivan (Robert Persichini) ponder the nature of decay and forgetting, losing one’s identity and usefulness as one’s memories gradually slip away. At the same time, the play explores memory as a force that can trap and freeze a person; memories of a home last seen half a lifetime ago prevent the sisters from moving forward where they are, even though they can’t go home again. Above all, the characters are lost, searching for purpose but finding little.

The most striking change in Santalucia’s production from the original is that the character of Vershinin, an army buddy of the sisters’ late father with whom Masha finds communion and love, is now female, her husband at home with their daughter. Christine Horne’s initial awkwardness as the officer who accidentally crashes Irina’s birthday party delightfully blossoms into a passionate vibrancy. Her relationship with Toal’s Masha is one of two sad hearts finding hope; it’s touching and compelling.

The adaptation is less successful in its removal of specific reference to time and place. The sisters no longer yearn to return to Moscow, instead referring to an unnamed larger city. In this attempt to avoid dating the script, however, it loses its anchor, missing some of its motivation. Some modern touches, including swearing and interjections like “he’s a vegan!”, occasionally clash in tone with more antiquated references and stretches of heightened dialogue, making the setting feel at times artificial, especially at the beginning when the dialogue still feels heavy in the actors’ mouths before settling and becoming more sprightly.

The real appeal of the show lies in the effective acting; if the show loses an anchor in specificity, it gains one in the humanity present on stage. As Ivan, Perischini is stellar in both his tender care for the sisters and his drunken rages as a man coming to terms with having outlived his usefulness. Thompson’s Irina seems as though she is living her life through a pane of glass even if she is physically present. Her distracted reaction to her brother’s cry from the heart, “Did you say something?” is a fabulous moment of heartbreaking comedy. In turn, we watch Yoganathan as Andrei shut down and dissolve into himself, silently sitting on the periphery or screaming into a blanket.

Seline’s weariness well beyond her years as Olga made me wish the character had more to do. Mousseau is deliciously awkward as a friendly man who can’t stop putting his foot in his mouth, and Maher Sinno as frustrated suitor Val projects a completely different, sullen social awkwardness that’s quietly dangerous and unpredictably explosive.

As another antagonist, Ruth Goodwin’s Natasha is delightfully nasty and self-centred, making an effective quick change between scenes from nervous, eager-to-please hopeful, to imperious, controlling wife. (In a nifty nod to Natasha’s gradual takeover of the house, set designer Perrin changes the couch colour to match that of her original party dress that everyone hates.)

The show subtly grapples with the concept of privilege, and I found myself wishing that commentary was even more highlighted and pointed. For example, it’s hard not to cringe at Irina bemoaning her ability to lie in bed all morning as she both romanticizes and dehumanizes the hard lives of the working class, comparing their labour to that of farm animals. Irina’s hopeful beau Nicolas openly talks about his lack of talent and his elevated position through pure nepotism, but others insist he is a “good man,” and he appears to be the best of the options.

The treatment of Anfisa the servant (played with blunt hilarity by Kyra Harper) is most telling; while Natasha most clearly abuses her, even those who clearly care about her, like Olga, still do thoughtless, selfish things based on their unconscious classist behaviour. For example, a bit of stage business where Olga calls for help after Anfisa, struggling under her load, begs to take a rest, only to hand over her own bundle to the volunteer rather than divesting Anfisa of hers, is silently telling. Anfisa’s eventual reward is added purpose, but also more labour.

This Three Sisters is worthwhile due to its thoughtful performances. However, the themes are so timeless in Chekhov’s play that modernizing the setting is essentially unnecessary, making it feel like the production doesn’t trust its audience to connect with it otherwise. Ironically, while the show’s motivation reportedly came from the pandemic, what it discounts is something else many of us came to learn from two years apart: sitting in a room together can transcend time, and is enough to move us.

Three Sisters runs through November 12. Tickets are available here.

Comments