REVIEW: Tom Rooney dazzles in world premiere of Michael Healey’s Rogers v. Rogers

Rogers v. Rogers, Michael Healey’s new satire at Crow’s Theatre, skilfully captures a heartbreaking duality at the centre of contemporary life, particularly in Canada: That a tiny group of corporations dominate many key industries, but the people running those companies often base their decisions on self-interest.

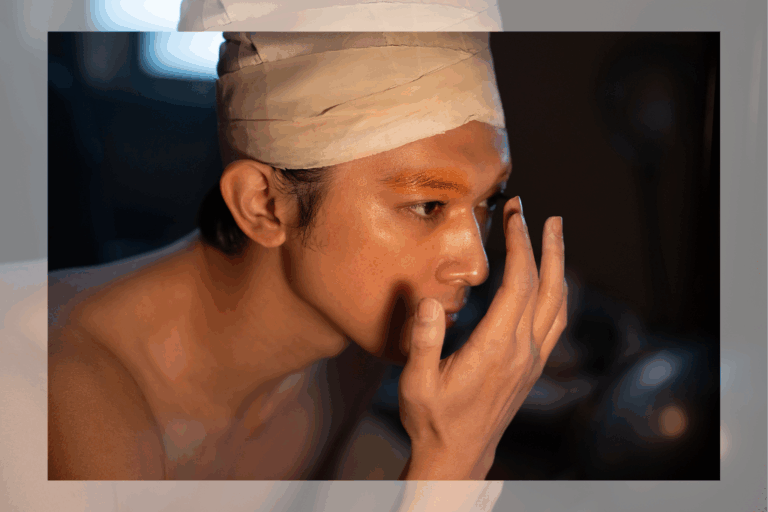

Familiar Crow’s face Tom Rooney plays every part in this 90-minute satire adapted from Alexandra Posadzki’s book Rogers v. Rogers: The Battle for Control of Canada’s Telecom Empire. Directed by Chris Abraham and positioned as a follow-up to Healey’s The Master Plan, the play brings a high degree of playfulness to its high-stakes subject matter. Rooney and Healey skewer the Rogers family with a disarmingly relaxed virtuosity that the surrounding production sometimes supports, and sometimes lets down.

Rooney begins the play as Matthew Boswell, Canada’s commissioner of competition since 2019 and the play’s moral conscience. Speaking to the audience, he introduces the larger context of the ill-fated legal battle his bureau led against Rogers’ 2023 merger with Shaw Communications. Then we’re off to family-drama land, with Rooney going back multiple generations to trace the rise of Rogers Communications, which has its origins in an early-20th-century vacuum company but was officially founded in 1960. It’s a whirlwind of a history lesson, but what’s key is the endpoint: CEO Ted Rogers dies in 2008 after proclaiming that his son Edward shouldn’t step into his role.

But Edward wants the job. Very, very badly. As the timeline advances and eventually overlaps with Matthew’s account of the Shaw merger, Edward tries various strategies to install himself as CEO. From the play’s title and marketing, I assumed we were moving toward a Succession-style, sibling-versus-sibling battle for the crown. But the rest of the Rogers family doesn’t seem to hugely want the gig. They’re just against Edward having it. The result is a revolving door of non-family CEOs, whom Edward sets up for defeat. (At one point, a random British guy even swoops in for the job — a development that should be familiar to fans of Ontario’s summer theatre festivals.)

Rooney rotates between voices, body language, and costumes as he traverses a remarkable range of dynamics. One of my favourite Rooney-isms is his knack for taking small behaviours — mumbles, eye rolls, little “humphs” — and blowing them up so they’re legible from several metres away. He uses these high-precision tools to chisel out character, bringing a welcome sense of realism to even the story’s most ridiculous figures (some of whom may be fictional, the program warns). Rooney also seems to embrace the occasional line stumble; instead of rushing to the next sentence and hoping the audience won’t notice, he does the jazz musician thing and plays the wrong note again, pausing over the blip and making it part of the character’s natural train of thought.

Grand comedic sequences contrast this fine detail-work. Particularly fun are the frequent scenes where Rooney quickly switches from character to character. In one memorable instance, he’s Edward, recalling how he successfully bolstered his reputation by taking a corporate power-player out to dinner — but he’s also that same businessman sharing that on his end, the experience was as bizarre as receiving an invitation to “Dracula’s crypt.” It’s a hilarious exchange that Rooney executes with aplomb, and it advances the text’s larger argument that these rich guys’ view of the world is totally fucking detached from reality.

The rapid-fire staging unfolds in proscenium configuration, and like Abraham’s two most recent productions in the Crow’s Guloien Theatre, it features video design by Nathan Bruce — both on the floor and on a wide strip of upstage screens. This design helps clarify the twisty narrative. As in The Master Plan, diagrams deliver complex exposition, at one point detailing Rogers’ rare dual-class share structure. And the floor changes colour when Rooney switches characters, which was fairly helpful even to this red-green colourblind viewer.

But the upstage screens remain on throughout the vast majority of the show, and whenever scenes focus more on character than plot, there’s little concrete information to display. Bruce and Abraham’s solution is to present patterns that are more-or-less abstract, like a semi-transparent animated spiral layered over a city skyline. The screens are bright enough that I found these less relevant videos distracting — particularly when combined with Thomas Ryder Payne’s near-constant sound design, which is most successful during the show’s narrative peaks, when swells of music confidently punctuate the story’s dramatic turns.

In the same vein, set designer Joshua Quinlan’s hulking centre-stage conference table works excellently during the show’s climactic board-meeting showdown, but in several other scenes feels like an obstacle for Rooney to dash around. The combined effect of these design choices is that I rarely ever felt the audience was alone with Rooney. And the considerable power of the main scene that veers from what I’ve just outlined — a speech by Matthew where the design steps back, the pace slows, and intimacy emerges — makes me wonder if it’s a missed opportunity that Rogers v. Rogers doesn’t have more visual and sonic rise and fall.

But thankfully the show has a lot of other things: It’s funny, features expert acting, and delivers a message Canadians should hear. I’d suggest Crow’s try to sell a filmed version to Netflix, but I’m not sure the streaming service would agree with Healey’s thesis.

Rogers v. Rogers runs at Crow’s Theatre until January 17. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments