REVIEW: Topdog/Underdog opens the Canadian Stage season with a snarl

When the characters in a two-person play are named Lincoln and Booth, you can take a guess how things might end up.

Such is the case in Suzan-Lori Parks’ Pulitzer Prize-winning Topdog/Underdog, presented in a moody production at Canadian Stage that binds together past and present in an explosive exploration of family, failure, and love.

Lincoln and Booth are brothers, bonded by parents who abandoned them and complicated relationships with their own Blackness. Lincoln, played here by a well-cast Sébastien Heins, spends his days impersonating the president for whom he was named, top hat and all. Every morning, he greases his face with white paint, stepping into a historical suit with a combination of disgust and amusement. Every day, for hours on end, he sits in a replica of Abraham Lincoln’s theatre chair, letting museum patrons take turns “shooting” him. It’s an act that for me evoked images of Atlanta’s Teddy Perkins, a disturbing display of whiteface that immediately suggests not all is right in Lincoln’s personal life.

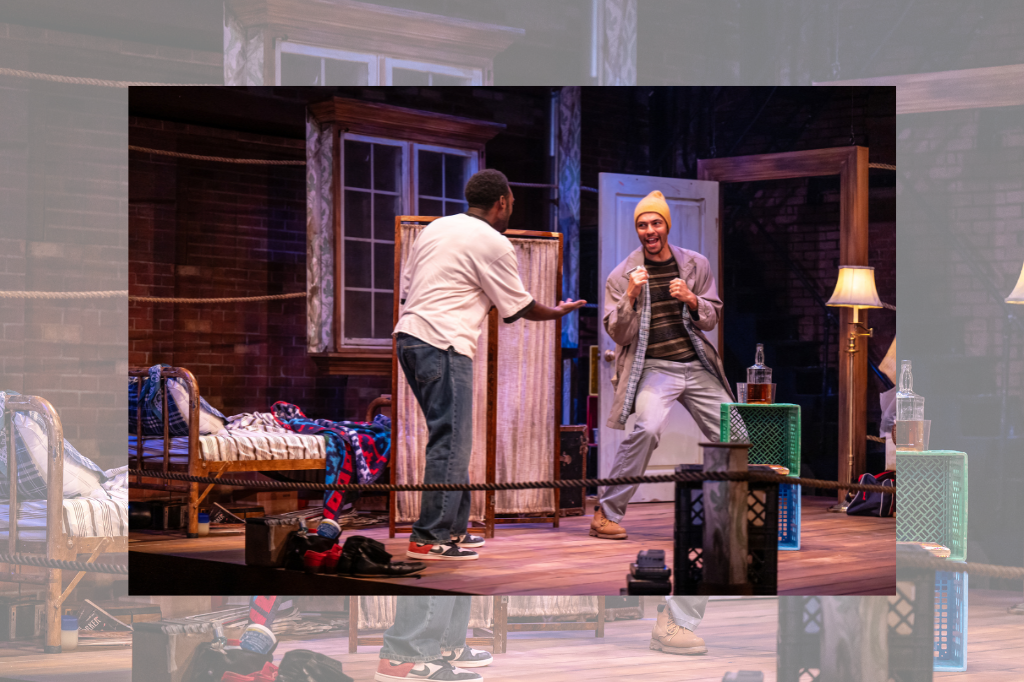

Booth, on the other hand, has struggles of his own – women, his sexuality, the annoyance of a precariously employed brother taking up space on his recliner. Mazin Elsadig, of Degrassi: The Next Generation fame, plays Booth with swagger and bite, a sharp foil to Heins’ more frenetic Lincoln.

The brothers and their myriad obstacles converge in the development of a card game scam, in which the dealer flips cards, and the player must follow a specific card as the deck shuffles across a table. Lincoln hopes to get away from this line of work – he’s on to better, more presidential uses of his time, he says – but in the end his brother, and the ease with which he games the system to snag an extra dollar, call to him.

Tawiah M’Carthy directs a dark, brooding Topdog/Underdog, in a three-hour production that often feels its length. Rachel Forbes’ set, a studio apartment tucked inside a boxing ring, is intriguing and off-kilter, placed such that Canadian Stage has had to re-jig the audience space of the Marilyn and Charles Baillie Theatre – audience members now sit in a corner formation that hugs the sides of the boxing ring, creating a sense of intimacy that, were it not for those bouncy, echoing exposed brick walls of the Canadian Stage building, would be quite effective. The set and the space in which it’s been placed create something of a vacuum for the energy onstage, almost leaving the performances from Heins and Elsadig to evaporate before they reach the audience.

Still, not all is lost – Parks’ script is a corkscrew of a play, twisting and twisting until the inevitable boom. M’Carthy has a firm handle on the play’s moments of anger and betrayal, and it’s in those moments that the chemistry between Heins and Elsadig gets to shine. Clothed expertly by Joyce Padua and lit well by Jareth Li, Heins and Elsadig keep the production from collapsing in on itself – just.

Parks’ play is one worth seeing, especially if you missed the Obsidian/Shaw Festival co-production in 2011. Despite being penned in 2002, the play has timely, audacious things to say about Black America and the history weighing it down. Topdog/Underdog is a fine season opener for Canadian Stage, if a little under-energized – it’s not impossible it’ll perk up over the course of its run.

Topdog/Underdog runs at Canadian Stage until October 15. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments