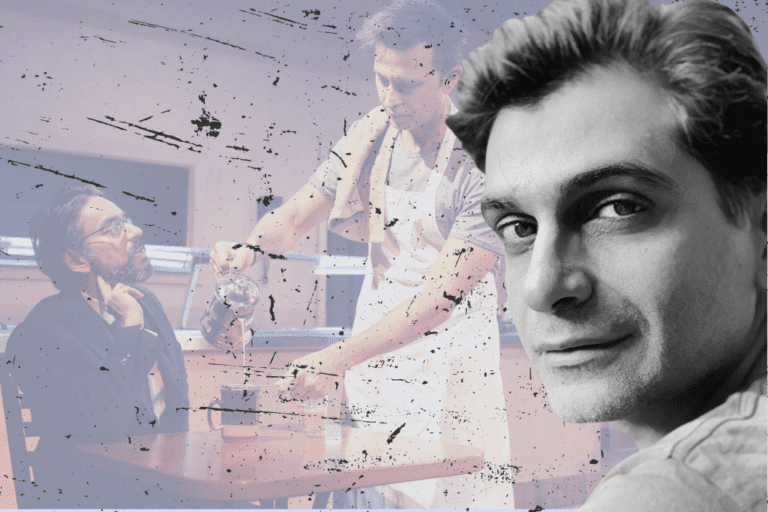

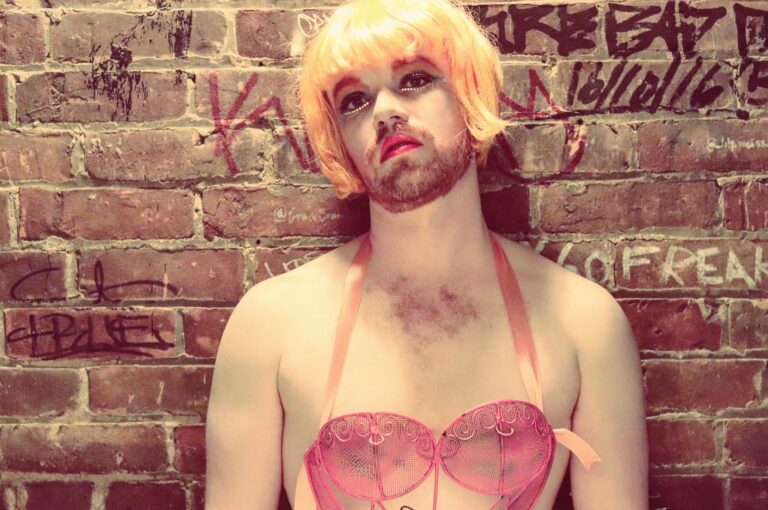

What I Wish I’d Known: Michael Healey

In What I Wish I’d Known, Graham Isador asks theatre artists what advice they’d give younger versions of themselves. The question is a jumping off point for larger conversations about the artist’s work.

In eleventh grade I wrote a paper on Of Mice and Men. I had learned about Steinbeck through a Rage Against the Machine cover of a Bruce Springsteen track and from there devoured the author’s writing with the vague hope of understanding working class struggles. The paper was misguided in that youthful way: I drew parallels between my shitty after school jobs and the painstaking hardships of Lenny and George. My naive attempt at solidarity with the depression era migrants was extremely funny to my teacher, who rightfully pointed out that—while my intentions were good—my minimum wage dishwashing job was hardly comparable to the plights of farmhands during the worst economic crisis in North American History. The teacher also said that I reminded her of a character from a play she loved called The Drawer Boy. She assigned the play as a part of my culminating activity.

While I began to read The Drawer Boy begrudgingly it quickly won me over. Up until that point my experience reading drama was slogging through half-understood Shakespeare texts, and pretending to have finished Waiting For Godot because the cute goth girl in my class said her favourite author was Beckett. Comparatively the words in Drawer Boy were easy to understand, they jumped off the page to create vivid and funny portraits of characters that felt like . . . you know . . . actual people. Finishing the text I clocked the playwright. Michael Healey. I should read more stuff by Michael Healey.

A couple of years later I’d encounter Healey again, this time not in print but on stage. His show Are You Okay? (a collaboration with Peggy Baker) opened up my mind to what theatre could be. In the show Healey played a version of himself, pontificating on the nature of free will and abandoning the artifice of a fourth wall to directly address the audience. He was funny, sardonic, and unencumbered in a way that would go on to inform my own writing and performance style.

Afterwards I followed Healey on Twitter, offering up a token of praise for the show, and was pretty surprised when he followed me back. Occasionally we’d shoot the shit online. I’d bug him for advice or chirp the writer for his love of HBO’s Ballers, a television show that answers the age old question: What if the Rock were a failing sports agent? The fact that a writer I admired so much was willing to play around was always something I was grateful for. Earlier this week we had the chance to chat about his body of work, mental health, and his new show 1979. You can read the interview below.

Graham Isador: In a Twitter Thread you posted last September you compared the writing in your first play Kicked with the writing in Drawer Boy. You noted the writing in Drawer Boy was much stronger and attributed a lot of the success to getting help with your mental health. A lot of young writers – myself included – associate being tortured with making good art. Why do you think that cliché persists?

Michael Healey: Once I began talk therapy and pounding the Wellbutrin, I had better access to my unconscious, and also my conscious editing abilities. I had more stamina and better concentration. I was a better artist once I got on the drugs and the chat. I think mental health is a big territory, and humans are diverse, and brain chemistry is inexact. I’ll say this, based on my own circumstances and observation: the intervention takes the time it takes. If you have some issue that turns out to need, say, six years of talk therapy and SSRIs, you can start that when you’re twenty-five or you can start that when you’re forty, but the time investment doesn’t change. Don’t try to gut it out, because that just burns years. Start at your earliest convenience. On the other hand, you can only start a meaningful intervention when you’re ready.

You also touched on the fact that you became more aware of your mental health struggles during theatre school. If you could tell the theatre school version of yourself the success you’d go on to have in the industry how do you think they’d react?

In theatre school I believed I’d be playing Hamlet at Stratford by twenty-four. This was in spite of the fact that I had no real love for the works of Shakespeare. I had a bit of talent, enormous self regard and no focus. If I could talk to myself from then, I would have said to go see more things, go see all kinds of art, and hurry up and figure out what kind of artist you want to be. I wasted a lot of time with very unfocussed ambition. I also had to wait before I could write. Due in part to messy mental health, but also to just youthful antsiness, I was in my thirties before I could sit still long enough to write something.

I can still only write for two to three hours a day. I spend a lot of time walking and thinking, but the act of sitting there, improvising from several points of view at once. I can only do that for a couple of hours max. I like to stop when I know how I’ll start tomorrow. Then I put on my pants and go get the kids from school.

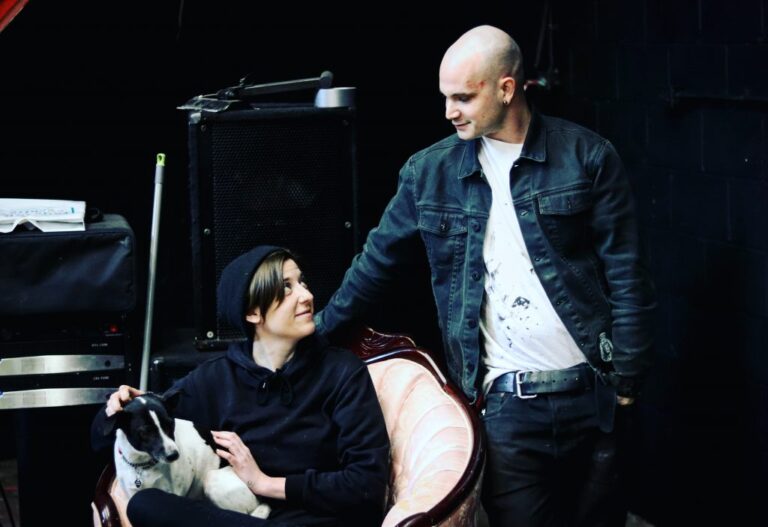

The only thing that keeps me sane while working in theatre/writing is the relationships I have with mentors and collaborators. Miles Potter has been a frequent collaborator throughout your career and you’re working with him on your latest show 1979. Can you talk to me about how you first met?

Miles directed me at The Blyth Festival summer of 1995. I was coming up with The Drawer Boy, sketching it out, and I gave him an early draft. He was really encouraging. He mostly wanted me to change the name of the character named Miles, but I refused. But he gave me good notes at critical stages, and so we built trust and a shorthand. It was 2012 before we worked together again, weirdly. We always wanted to work together, but sometimes he was busy and sometimes new plays were attached to other directors. We’ve done it enough now that we are comfortably up in each others’ biz. I offer direction occasionally, he suggests unvarnished dramaturgy.

You’ve talked about how a jumping off point for 1979 was different perspectives on Joe Clark. Can you elaborate on that point?

I did lots of research, but I had no interest in getting the truth of the situation depicted in the show from Clark himself. I never attempted to interview him. I wanted the freedom to show Clark as a hero, a dupe, a smart guy, a loser, a principled guy, all of it. I wasn’t after the truth, I wanted to tell a story about all the aspects of leadership, of politics, of public service, of the basic idea of serving others. Because the point of the play isn’t to document the past, it’s to discuss what’s happened to those things since 1979. Because he’s the vehicle for this discussion, not the point of the show, I don’t care whether Clark ever sees it. People ask all the time: wouldn’t it be great if Joe came? But I don’t care. It’d be like getting excited a bunch of farmers saw The Drawer Boy.

I want to close with this thought. 1979 is the latest in a body of work that’s spanned decades. At this stage of your career is legacy something you think about? Do you have any thoughts on what you’d like your legacy to be?

Evidence suggests my legacy will be [that] I was Emma Healey’s father.

Comments