REVIEW: Takwahiminana explores what healing means when the past never quite lets go

The first thing you hear is the sound of choking.

It’s a visceral sound that makes the hair on the back of your neck pay attention, a sound that means danger. It’s a sound that permeates the dreams of Sharon (Michaela Washburn), as she imagines she’s swallowed something that now has to come up.

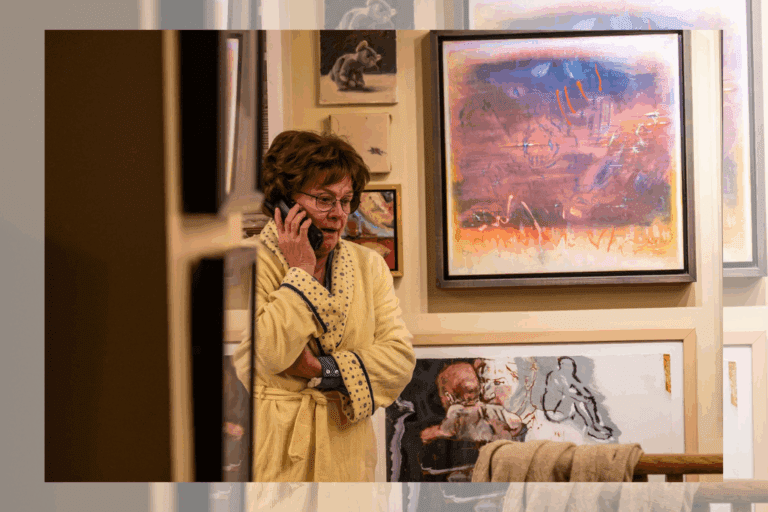

In playwright Matthew MacKenzie’s Takwahiminana, staged at Soulpepper by Punctuate! Theatre and director Mike Payette, what comes up is an hour-long monologue about Sharon’s rocky life as a constant outsider. A Métis woman raised in India by an absentee father and depressed young mother, she fit in nowhere, ostracized both in India and on her return to Alberta.

Now, Sharon stares down the end of a 20-year affair with chef Claude, who fetishizes her for her body and for her knowledge of Indigenous ingredients, which he uses in his Canada-themed menus for “authenticity.” Stuck at the end of the dinner party table both literally and metaphorically, Sharon finds she can no longer bear the judgmental flared nostrils of Claude’s wife — when a sudden culinary misstep changes everything.

Takwahiminana means chokecherry in Cree and Michif. A fundamental fruit in Cree culture, it can only be eaten when fully ripe, or it’s toxic; even when ripe, it’s bitter enough that it requires plenty of sugar, primarily consumed as preserves or syrup. The flipside of this sour, sometimes noxious “bird cherry” is its bark, used as a restorative salve. MacKenzie’s play ascribes a similar dichotomy to life, saying that sometimes it’s only by accepting the bitterness of past events that we can use them for healing in the present.

While MacKenzie’s lyrical, detailed imagery and storytelling are always a delight, there’s something astringent and detached about Takwahiminana that produces a distancing effect, preventing it from reaching the emotional highs of his other recent work.

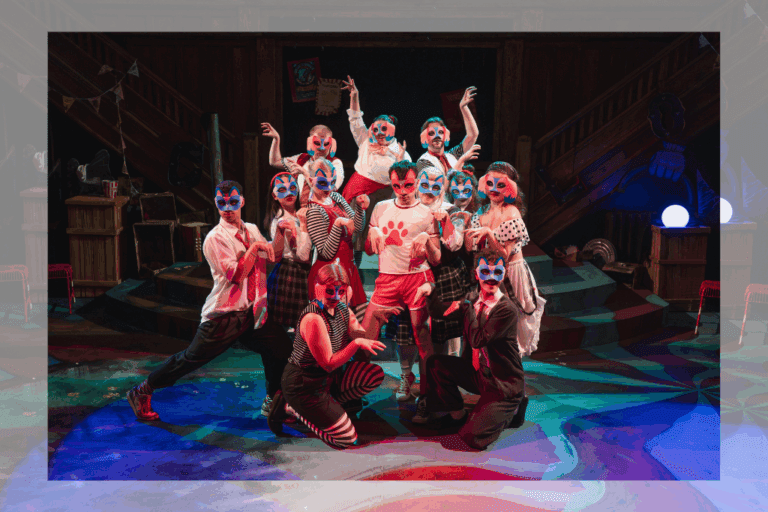

In Bears, MacKenzie used a dancing chorus behind a solo performer to great emotional effect (and two Doras); the eight women behind protagonist Floyd became the animals and plants that gave him the mental strength to flee after committing an act of sabotage against Big Oil.

MacKenzie returns to this technique in Takwahiminana, surrounding Sharon with five Bharatanatyam dancers (Prithvi Castelino, Vanessa Mangar, Kajaanan Navaratnam, Swetha Pararajasingam, and Naveeni Rasiah) who silently become figures in Sharon’s life story, from the monkeys in her youth who accept her into their group, to the Canadian field hockey players who ostracize her.

This time, though, there’s less of a compelling reason for the dancers to portray moments from Sharon’s life; their part feels illustrative rather than interactive or inspirational to the main character, a representation of the past rather than a push toward the future. This directorial choice makes the dancers seem closer to accessories than full participants in the story.

The script states that Sharon used to dance Bharatanatyam, but the otherwise expressive Washburn never fully joins in the movement; this emphasizes her status as a constant outsider, but results in the show feeling more static than it physically is. Luckily, Anoshinie Muhundarajah’s precise choreography often makes the dancers mesmerizing to watch, as they show an impressive amount of bodily control in sharp movements or when suddenly dropping to a crouch on the floor.

Set designer Dawn Marie Marchand’s undulating backdrop of fabric ribbons contrasts with and accentuates the beauty of crisp movements. Amelia Scott’s attractive projections of starry nights bring the backdrop to life, gaining depth when the dancers also illuminate it from behind with handheld lights. Derived from the Persian boteh meaning shrub or flowering plant and in use in India since at least the 16th century, the bright buta (also known as paisley) designs painted on the floor seem somewhat at odds with the soft colours of the backdrop, but the vivid teardrops do add vibrancy to an otherwise cool space.

Takwahiminana is most effective when it embraces the absurd, introducing Sharon’s impossibly world-travelling pickle jar, or in moments of tenderness when Sharon finds community with her grandmother, another solitary woman who shows her how to heal.

Washburn gleefully recounts a firecracker of a gross-out climax. Claude’s glaring misfire in trying to make a legendary French dish “Canadian” is as fun as reading one-star reviews of recipes online — you know, the ones where hapless cooks complain that substituting library paste for the recipe’s chocolate made their brownies taste bad. That recipe gone wrong is another effective metaphor, showing that you can’t simply take parts of another person’s identity to serve your purpose, and clarifying how little Sharon belongs in Claude’s world.

Because Sharon spends most of her time defensive and closed off, it’s easy to appreciate the twisty, cyclical story she tells but harder to connect with her, even in her more vulnerable moments and even considering Washburn’s appealing stage presence. Maybe it’s the way Sharon tells her story in third person, as if she’s talking about somebody else; maybe it’s how she stonewalls even her chorus, never really allowing herself to take part in the dance.

The story’s expulsion from Sharon’s throat is a healing act, but Takwahiminana is still finding the balance between bitter and sweet.

Takwahiminana runs at Soulpepper Theatre until May 11. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments