REVIEW: Here For Now’s well-acted Reproduktion attempts to tackle too much

Spoiler alert: The seventh paragraph of this review includes brief discussion of Reproduktion‘s final scene.

More than anything, Flora and Neil Smith want a child.

Carol Bolt Award-winning playwright Amy Rutherford’s Reproduktion explores the couple’s desire for children, and the lengths they’ll go to in order to achieve that dream. Marie Farsi directs the genre-bending play’s world premiere production at Stratford’s Here For Now Theatre.

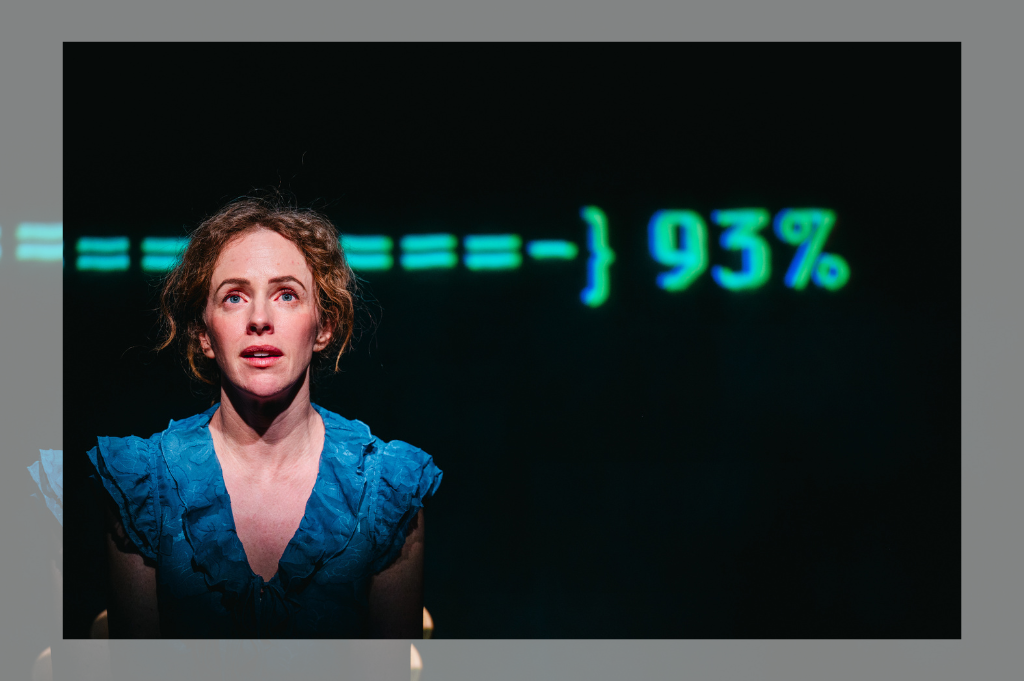

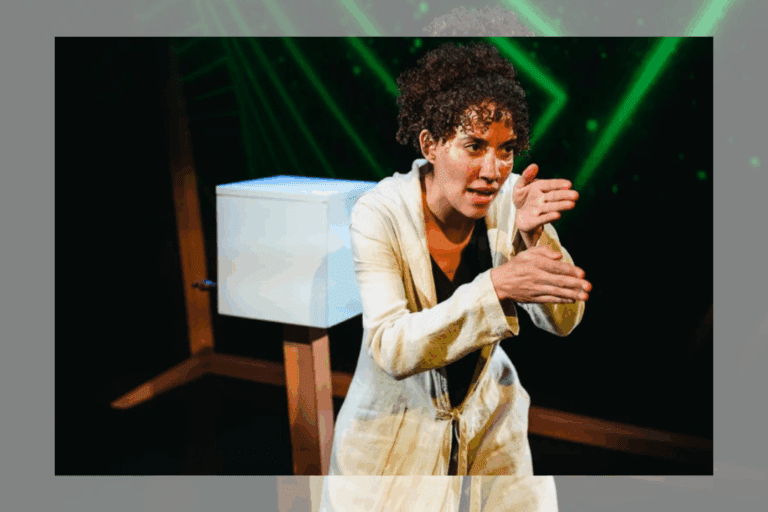

After years of failed infertility treatments, entrepreneur Flora (played with sensitivity and drive by Here For Now artistic director Fiona Mongillo) and her husband Neil, a former biologist (Tyrone Savage), are at a loss. When a member of their church recommends they try an experimental new treatment from a clinic in Sweden, the Smiths jump at the chance. At the clinic, they meet Dr. Kult (whose name is the subject of several jokes), played by Rylan Wilkie, as well as Kult’s wife and assistant Nurse Bitta (Maggie Huculak). The two assure Flora and Neil of their procedure’s 100 per cent success rate before plunging them into a drug-induced, time-travelling dreamscape, the end result of which, they’re told, will be pregnancy.

Over the next 80 minutes, Flora and Neil move between the real-world clinic and dreams of Sweden in centuries past, all the while questioning their reasons for wanting a child in the first place, and wondering just how far they’re willing to go to see that dream realized.

Rutherford’s script is ambitious and the material it covers is complex: in addition to the central throughlines of infertility and medical intervention in reproductive struggles, it touches on Flora’s connection to her mother and grandmother, her sense of disconnection from her Swedish heritage, and her relationships to her husband and her faith. The genres it engages are similarly wide-ranging — billed as a dramatic comedy, the play moves (often abruptly) between drama, comedy, fantasy, satire, and occasionally horror.

While Farsi’s production makes a significant effort to meet each of these topics and genres, the narrative itself feels disjointed, and Rutherford leaves those intriguing thematic threads unresolved as the play progresses. Flora travels back in time to (what is implied to be) a maternal ancestor’s wedding night, but the play doesn’t flesh out how that experience informs her understanding of herself, her heritage, or her understanding of motherhood — and references to Sweden more broadly are often played for laughs. A deeper engagement with ideas of heritage, place, and family would have strengthened Flora’s character development, and the narrative at large.

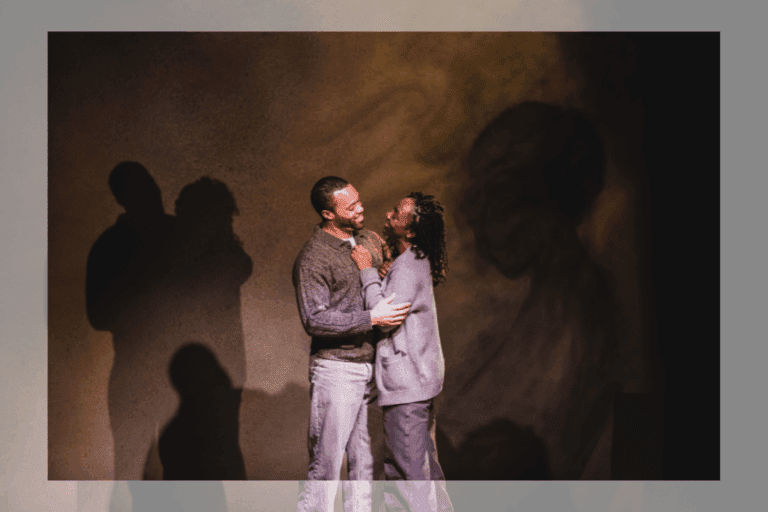

The play arrives at its eventual reflection on what makes a meaningful life without children in its last few minutes. In that final scene, Flora and Neil move from grief to acceptance of their inability to have children with an ease that seems incongruous with the extremes they’ve traversed in pursuit of that goal. It’s challenging to see how these characters could reach this level of acceptance so quickly, and unclear how their relationships to each other, and the faith they so highly prioritize in the play’s opening scenes, have changed.

In a political climate where reproductive rights are under increasing threat and scrutiny, some of the play’s glancing moments carry a heavier weight than the play fully reckons with. While the script quickly moves past both Neil and Dr. Kult pressuring a hesitant Flora into the experimental treatment, and Neil’s implied anti-abortion stance, these brief references nonetheless gesture toward a darker tone that’s at odds with the play’s framing as a dramatic comedy. There are important questions here around autonomy and consent, but these go largely unexamined.

Farsi’s production is led by a couple of standout performances. Mongillo’s Flora is earnest and believable in her desire for motherhood, and her bewilderment during the play’s first time travel sequence offers some of Reproduktion‘s most effective comedy. Savage’s Neil also shines, particularly in the play’s quieter moments of grief — I found his performance in the final reckoning between Flora and Neil genuinely moving.

The design, too, is strong. Building on the minimal but effective elements of Patricia Reilly’s set design, Jonah Luscombe’s projections help to guide the audience between the beige walls of Dr. Kult’s office, the small Swedish village where (we assume) Flora’s ancestors lived, and a mystical cave. Louise Guinand’s lighting adds to this sense of place, and in one memorable moment carves two separate rooms at the clinic out of Here For Now’s small playing space. Adam Campbell’s sound design sees prerecorded dialogue mesh smoothly with the actors onstage (Mongillo’s interactions with a computerized interviewer are particularly seamless), and reverb effects on the actors’ mics add to the sense of dreaminess.

Reproduktion is well-acted and well-designed. It’s unfortunate that its script feels so scattered.

Reproduktion runs at Here For Now Theatre in Stratford, Ontario until November 30. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments