What I Wish I’d Known: Andrea Donaldson

In What I Wish I’d Known, Graham Isador asks theatre artists what advice they’d give younger versions of themselves. The question is a jumping off point for larger conversations about the artist’s work.

I’m sitting in a coffee shop across from Andrea Donaldson and we are talking about burnout. It isn’t the conversation I had been expecting to have with Nightwood’s new artistic director. I had started off our chat with a lowball question—why did you want your new job—and had expected platitudes in return. Maybe a riff on contributing to the legacy of the institution or a few sentences about the generalized notion of community building, something all Toronto theatres seem obsessed with but so few can actually define. Instead Donaldson launched into an impassioned speech about how in our current theatre ecology we are expected to do so much work for less money than we are worth. She spoke about how creators are rarely given opportunities to grow work until it is artistically ready. How companies will often stretch themselves to get more of everything rather than giving proper resources to fewer projects. How that mentality bleeds down to the people working there.

I sipped at my Americano, my third of the day, and realized that after the interview I had to write a press release for the theatre company I work for. After that I had to schedule all of the company’s social media for the week, answer the two dozen emails in my inbox, attend staff meeting, then talk through what’s needed for our next newsletters. When I got home I had an article for another publication to write. If I finished that maybe I’d have time to work on my new play for an hour before bed. The idea that maybe I could do less and maybe that would be good for my theatre company and my own art never occurred to me. There wasn’t any time to think about it and it is also what everyone I know in theatre is doing too. Hearing Donaldson recognize the problems with that set up made me feel both validated and hopeful.

Over the course of our hour long conversation Donaldson said several other things that I was extremely grateful to hear. We talked about her history as a director and dramaturge. The work she had recently done with Nightwood with Grace and Lo (Or Dear Mr. Wells) and the upcoming gigs at Soulpepper with Betrayal. Donaldson spoke with warmth and humour about the work. It made me extremely excited to see where she takes Nightwood with her leadership. You can read part our our conversation below.

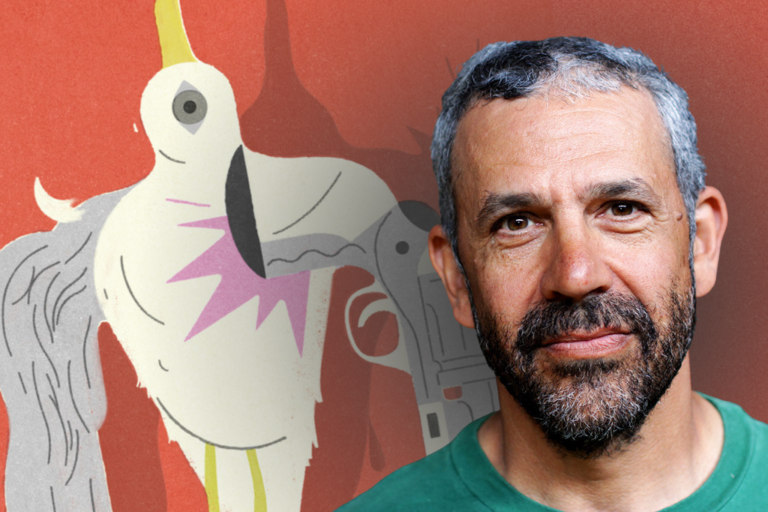

Andrea Donaldson / Photo by Graham Isador

Graham Isador: Over the course of your career you’ve had a lot of different roles, creatively and with admin. Did jumping around a lot inform your process now?

Andrea Donaldson: In the beginning of my career I equally identified as a creator/performer and as a director. I didn’t really feel like I fit in as an ”actor-actor” or as a “playwright-playwright” – in fact impersonating either of those roles made me feel like a lonely-outsider-weirdo. But still I lived to embody and create. What made sense to me was to create new work from the least expected impulses; the most unfettered imaginative sphere–not to uphold power by re-producing texts that had been agreed upon as masterful and that I felt utterly excluded from. Often my work came from imagistic and physical impulse and then I applied dramaturgical principles–why this, then that?–if this, what next? I was drawn to forming collectives and creative partnerships that didn’t overvalue text as the dominant element. I valued initiating works from an artistic inquiry or parameters that would unleash unordered artistic material to then sift through and make sense of. When a script finally emerged, I loved to “smash” the text that seemingly ought not to combine and see what emerged from that. Within that time, despite identifying as a theatre artist, I really wondered whether I liked play-plays at all.

What did that look like to you?

Finding out how a career might work was kind of hard, given that I felt like my artistic arena was outside of what a ‘normal’ theatre person might do. I needed people and I’d come to Toronto leaving behind a company I’d co-founded in Vancouver. Ultimately it was in finding Nightwood’s Hysteria Festival–“a multidisciplinary festival of female artists” with Buddies in Bad Times Theatre that gave me my first moments in Toronto to reveal myself artistically and earn my first honorariums – those $100 cheques meant so much! I was reminded recently at Hot Brown Honey of my first Hysteria offering: a call for artists to reimagine the bra, which inspired me to construct pair of enormous lop-sided papier-mâché breasts, painted to my skin tone with huge areolas, hooked together by a bra-like structure that I proudly wore as I strutted their catwalk. In another, fellow weirdo Erin Shields and I situated a performance piece where she climbed up and around the toilet stalls in Buddies during intermission hunting for her lover she’d flushed down the loo. In another we sent up dinner party etiquette, a physical piece incorporating dozens of spoons, and in another I performed a solo with an ironing board as a 50’s housewife who had freed herself from the shackles of a marriage to follow her salacious love of a women. These little moments were actually huge moments of being recognized as an artist and finding my people. I want to help make some of those moments. Because stick-to-itiveness and resilience is key to having a career, but being seen and included when you’ve got no footholds is everything.

Do you think that process informs how you’ve mentored others?

I always had a sense that I would have to make space for myself, and for me that always included or necessitated a vision to artistic direct. Even before I graduated theatre school in BC I had formed a company and was working for other alternative companies, as I knew that as an artist I wouldn’t be the kind who gigged in a traditional way. And then at a certain point my desires shifted from wanting to be on stage and wanting to be a maker, to wanting to facilitate the making. Now my sense of authorship as a director and as a dramaturge expresses itself in more of a “holding space” kind of way and in creating a vision for art to emerge from. I feel like that directly extends to how I want to lead Nightwood. I think of myself as someone who establishes the container and holds it dutifully but ultimately I’m not the featured artist. I love being in rehearsal and I love making art, but I actually don’t really care if my work is featured in the company, though I suspect it will be.

The set up for these interviews is asking what advice you’d give to your younger self and what they’d think of what you’re doing now. How would you answer those questions?

Since I was a kid I was fighting for marginalized work to be valued and made it happen. I’ve always loved doing impossible things and making projects happen against all odds. I think my younger self would be more surprised by some of the ‘normal’ things in my life–that I’m functional, that I have a child, that I’m able to get said child to school on time, that I pay my bills–than feel surprised by where I’ve landed. And despite some requisite impatience, I do not wish I would have arrived at certain opportunities in my life any sooner than I have. As an emerging artist I was always over-confident and nervy, which was totally necessary, but with that came a tendency to push, to control, to demand perfection. I’m much more interested in being open, being uncertain, and trusting.

And trusting and openness and uncertainty requires a lot of preparation and an ability to be present. And it’s easy for any freelance person, perhaps especially those working for love or a calling to give too much and rot themselves and rob themselves of their present tense. I hold myself to pretty high standards–I hate saying no to projects and people that turn me on. I want people to feel the love and support and I want to consume as much art as possible. But I’ve gone too hardcore at times and I’ve paid for it. And of course I’ll do that many more times before I die, but ultimately what I learn from messing up with my personal equation for balance is that I ruin things for myself and those around me. And my tolerance for that has gotten very thin. I don’t like myself when I can’t be present. I don’t like myself when I am decision-making out of fear or anxiety. And actually I have a lot of people who count on me to be their rock.

I’m a director who believes in sharing my own vulnerability and I am also here on this planet to let people know that we’re going to be ok, that we’re going to figure it out, that I’ve got them, and the safer they are the more they can be daring and free. That’s part of my power–to hold that space for my creative teams, my actors, my stage managers, my partner, my child, my family and my friends, strangers, acquaintances, women, men, others. So I have to be balanced and strong. And I have to imagine if that makes me more creative and playful and joyous and ultimately in my flow, then the more I can create that vibe for others the better we’ll all be. And that has to be top down if I am holding decision-making power. And it’s delicate because care is so nuanced. And taking care doesn’t necessitate removing resistance, which is also vital. But I believe in a huge distinction between pressure and stress. One is exciting and passionate and one is toxic.

Is that the same spirit you want to bring to the leadership at Nightwood?

My interest in stepping into the helm at Nightwood is really a continuation of what I have done in a freelance capacity kind of forever. I want to shape works and create an ambitious framework for the work and the kind of work we do with a deep mission to shape how we work. Some friends or colleagues have said how nice it will be for me to be able to do whatever I want – I actually don’t feel that at all. I feel like taking this role on has done the opposite for me. I’ve been a exceptionally happy freelancer, in service to many, but certainly less bound by constraints. However, I’m someone who thrives with constraints and who thrives by responding to others. I’m also really resourceful and love solving problems: I love making things hum. So I kind of see myself as the wizard behind the curtain. The people are the thing. The art is the thing. The community feeling pushed and enlivened and inspired is the thing. So by what measures? How can I/Nightwood be an agent of that? And how in so doing can we bring up the next crop of incredible artists who are either young in craft by virtue of having being excluded or young in craft by virtue of being fresh onto the scene. So like with a rehearsal process, I’m researching and preparing exhaustively (but not too exhaustively) to step into that role on May 1st, so that once I arrive, I can be as responsive and in my flow as possible to ensure the strength of the company as an enduring, empowering force for this community.

Andrea is currently directing Erin Shields’ Beautiful Man playing May 4-26 at Factory Theatre. For for information and to order tickets click here.

Comments